When the Supreme Court decided Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963, it was celebrated as a shining example of U.S. exceptionalism and democracy. In guaranteeing defense counsel to people too poor to afford representation, the court extended the Founders’ promise of fairness and equality to the criminally accused. However, sixty years later that promise remains unfulfilled.

Among the many remaining barriers to adequate defense—excessive caseloads, staffing shortages, and attorney inexperience—one that receives little attention is the inability of indigent clients to choose their attorney. For people who can afford to hire a defense lawyer, the Constitution protects their right to select their lawyer of choice. This is not so for those who must rely on the public defense system. They must accept the lawyer the court appoints. This disparity can have a particularly detrimental impact on indigent Black defendants. Given the lack of racial diversity within the legal profession—less than 5 percent of lawyers are Black—the system overwhelmingly appoints white lawyers to represent Black defendants. This often intersects disastrously with racial bias, whether that be implicit bias or, as in the following example, overt racism.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court will soon rule on a case, Commonwealth v. Anthony J. Dew, that hinges on the question of whether an appointed counsel, Richard Doyle, rendered ineffective representation to his client Anthony Dew. A trial court appointed Doyle to represent Dew, a Black Muslim man facing criminal charges. Dew entered a guilty plea and was sentenced to prison. Dew later learned that while Doyle was representing him, Doyle posted over twenty bigoted and racist comments on Facebook disparaging Black people and Muslims—including comments about his own clients. Armed with this information, Dew sought a new trial based on ineffective assistance of counsel.

This essay is from the series

Beyond Gideon

A collection of essays examining how—or whether—public defenders can meaningfully contribute to the end of mass incarceration.

Several civil rights and racial justice organizations filed briefs supporting Dew’s argument. The brief filed by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund goes so far as to argue that the court should find that Doyle’s conduct resulted in a conflict of interest, rendering defense counsel ethically incapable of providing adequate representation to people of color and Muslims. The court will likely rule on the case in the summer of 2023; other states will certainly be watching closely.

Successful attorney–client relationships require loyalty on the part of counsel and trust on the part of the defendant. Research shows that racial bias within the relationship can affect every facet of representation. Despite this, if an indigent Black defendant is appointed racially biased defense counsel, the defendant has no right to select a new lawyer of their choice.

There is little recourse if an indigent defendant believes their appointed lawyer’s racial bias negatively impacted their case. Proving ineffective assistance of counsel is notoriously difficult for everyone, but Black defendants experience an even greater degree of difficulty due to racist stereotypes about Black people who receive social benefits. On top of this, although the Sixth Amendment right to counsel specifies the right to effective counsel, courts rarely take the view that defense counsel’s racial bias constitutes ineffective representation.

Two decades after Gideon, the Supreme Court’s decision in Strickland v. Washington (1984) established the ineffective assistance of counsel standard. The standard requires a defendant to demonstrate that their lawyer’s conduct fell below an objective standard of reasonableness—and moreover that, had it not been for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the case would likely have had a different outcome. Proving both of these things is nearly impossible, for at least two reasons.

First, racial bias is often implicit, occurring without the actor’s conscious thought—and without a smoking gun, as in the Massachusetts case. However, in the context of indigent defense, implicit racial bias can impact representation in significant ways. This includes how public defenders evaluate evidence, interact with clients, and accept punishment on behalf of their clients.

Second, when evaluating whether counsel’s performance was deficient, courts rely on a presumption of professional reasonableness and competency—a set of presumptions based on white norms. This means that courts rarely believe that a lawyer’s conduct was bad enough to affect a ruling. Even in cases involving defense counsel who have been intoxicated or asleep during representation, courts have neglected to find prejudice.

At the root of the problem is that the ineffective assistance of counsel standard does not account for racism.

In Michel v. Louisiana (1955), a precursor to Strickland, the Supreme Court was asked to determine whether an appointed defense lawyer rendered incompetent representation. The Jim Crow–era case involved Black defendants indicted by all-white juries for raping white women. All were ultimately sentenced to death. Despite the fact that one of the lawyers did nothing on the case for a year before withdrawing, the Court neglected to find counsel’s conduct constitutionally deficient. The Court’s decision seemed to indicate that indigent Black defendants should be grateful to have a lawyer—any lawyer, even one who couldn’t be bothered to mount a defense. It also spoke to the justices’ unwillingness to credit a poor Black man’s accusation of incompetence against a white lawyer. The Supreme Court then relied on Michel when it formulated the standard for ineffective assistance in Strickland.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

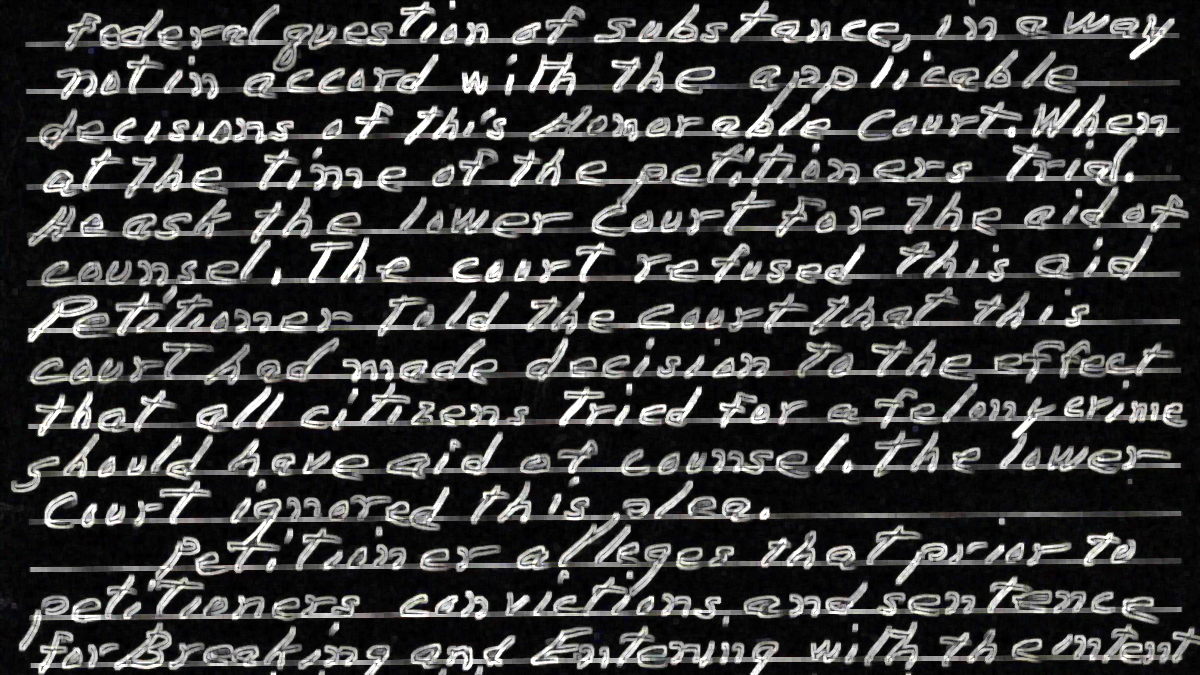

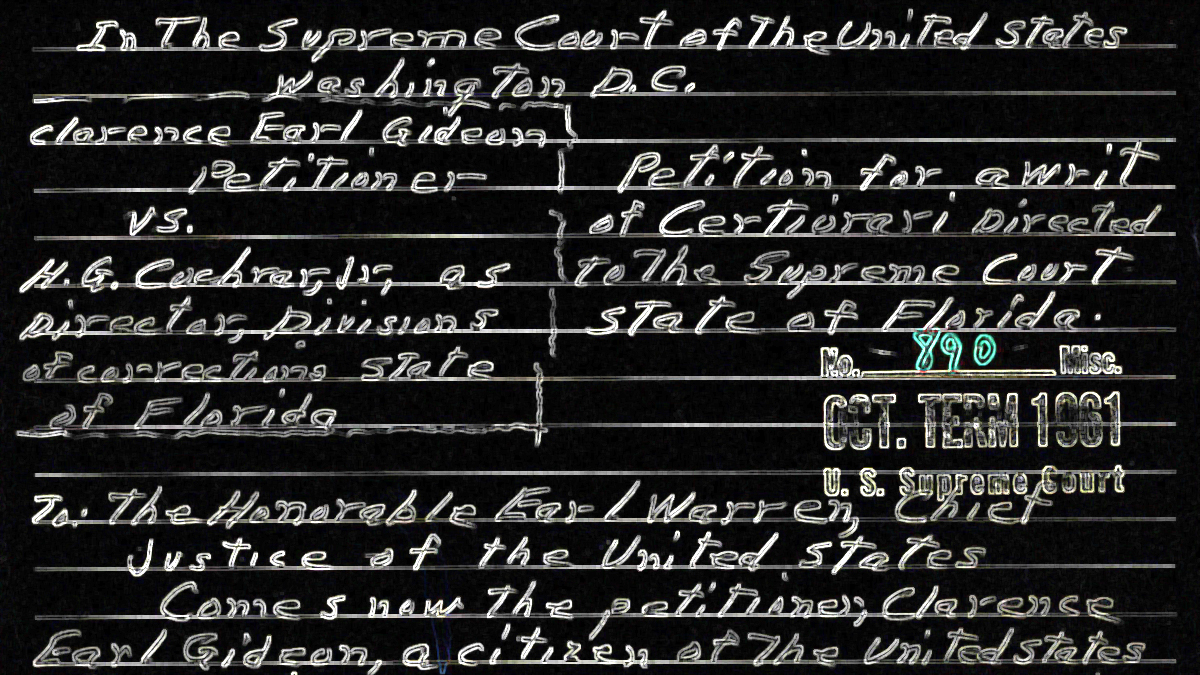

Gideon was one of a series of decisions that the liberal Warren Court issued during the 1960s that advanced individual civil rights and liberties. Yet in its ruling—written against the backdrop of the civil rights movement—the court avoided grappling with racial bias. That Clarence Gideon was a white man was no coincidence. Though the decision does not mention Gideon’s race, it appears in the brief filed by the state. Racism and white supremacy underscored the Court’s perceptions about the “deserving” poor and continues to impact court determinations of whether a client received constitutionally effective representation.

Even when counsel’s racial bias is obvious and explicit, courts often refuse to recognize that this violates a defendant’s right to effective representation. For example, in 1990 Georgia prosecutors sought the death penalty against Curtis Osborne, a Black man who was charged with two murders. The court appointed defense attorney Johnny Mostiler to represent Osborne. The prosecution was willing to offer Osborne a life sentence if he pled guilty, but Mostiler did not communicate this to Osborne. Instead, the case proceeded to trial, and a jury sentenced Osborne to death.

Osborne didn’t learn about the plea offer until much later, while working with new lawyers on an appeal. Osborne also learned that, prior to trial, Mostiler had referred to him as a “little n___er” who “deserves the death penalty.” Armed with this new information, Osborne sought reversal of his conviction and sentence, alleging that the state denied him his Sixth Amendment right to effective counsel. Osborne argued that Mostiler’s explicit racism prevented Mostiler from sharing information about the plea offer. The appellate court tiptoed around counsel’s “n___er” comment and dismissed Osborne’s appeal as procedurally barred. Despite calls for mercy from former president Jimmy Carter, the state of Georgia executed Osborne in 2008.

In most cases, though, defense counsel’s racial bias is not as explicit. I represent a client on federal death row in post-conviction proceedings. The trial court appointed the client, who is Black, four white lawyers, all of whom had trouble connecting with him. The lead counsel stopped visiting the client in pretrial detention, and the investigator, also white, unsuccessfully badgered the client to accept a plea offer. The defense team then hired Black surrogates to “level” with the client, another failed tactic. Unprepared, the team headed to trial. During jury selection, defense counsel neglected to question jurors about their racial bias even though the crime involved a white victim and the jurisdiction had a history of white supremacy and anti-Black racial terrorism. The defense counsel failed to object when the prosecution repeatedly referred to the client using racially coded language and dehumanizing terms. During sentencing, the defense counsel fumbled in presenting the client’s case for life.

Was the counsel’s conduct racist? Perhaps not. Was it racially biased? Likely. Even so, there is no clear remedy.

Defense counsel make countless decisions, both large and small, when representing people accused of crimes: how much time to devote to investigating the case, whether to challenge the prosecution’s evidence, assessing whether the client should plead guilty, and what issues to preserve for appeal. Racial bias can impact all these decisions, even when it remains undetectable.

The extent and impact of such bias is unlikely to show up in a trial record, making the appeal of these biased decisions challenging. In that way, Doyle and Mostiler are exceptional because they explicitly expressed their racism. But what of the countless defendants of color represented by defense lawyers harboring implicit racial bias? Such lawyers may spend a little less time on the defendant’s case, neglect to seek out a witness with helpful information, and convince the defendant to accept a slightly lengthier sentence. The legal standard, built on the promise of fairness and equality in Gideon, does not yet account for such conduct.

There are at least three potential solutions to this crisis. First, the Supreme Court could remove the prejudice requirement from the ineffective assistance of counsel standard. Justice Thurgood Marshall, who dissented in Strickland v. Washington, was the earliest critic of the prejudice requirement. He argued that the Constitution entitled all defendants to effective representation, including those who could not prove that, absent counsel’s deficient performance, they would have been acquitted. Alternatively, the high court could shift the burden of proving prejudice to the state, which some lower federal courts required pre-Strickland. Then the state would have to prove that counsel’s deficient performance did not affect the outcome of the defendant’s case, rather than the other way around.

Second, the court could extend to all indigent defendants the right to choose their lawyer, making good on its promise of equity between those who can afford counsel and those who cannot. This would allow indigent defendants the freedom to choose a lawyer whom they trust. By necessity, public defender offices would then also have to prioritize recruiting and retaining more Black lawyers and lawyers of color.

Third, the government could prosecute fewer people. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, jurisdictions across the country ceased to prosecute drug possession, sex work, trespassing, and other low-level offenses. A decrease in the prosecution of crimes associated with poverty would automatically decrease the number of Black people ensnared in the criminal legal system. In the short term, a decrease in prosecutions would also decrease public defender caseloads, alleviating one of the conditions under which racial bias in decision-making flourishes. In the long term, a decrease in prosecutions would help address the presumption of Black criminality and ultimately decrease anti-Black racial bias.

The best way to fulfill Gideon’s promise of equality and fairness is to end the mass criminalization of poor people of color and render the need for public defenders obsolete.

Image: National Archives/Inquest