In a study published in the medical journal The Lancet Public Health in February, a group of researchers from Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health found that as jail incarceration rates rose in a sample of 1,094 counties in the United States, so did the rate of mortality due to several causes of death. After controlling for a number of potentially “confounding” factors, such as county median age and political control of the state legislature, they found that this association between jail incarceration and death in county residents was strongest for deaths due to infectious diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, substance use, and suicide.

The idea for this study, which adds to a growing body of research showing the harms of mass incarceration to entire communities, arrived on the heels of an earlier study, published in a special edition of the American Journal of Public Health, that had already drawn a link between jail incarceration and general mortality. As the nation grapples with other crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic and the plight of opioid overdoses, these findings underscore how our public health responses necessarily must account for how incarceration may be making matters worse for communities.

In this narrative essay, the lead researcher for the Lancet study, Sandhya Kajeepeta, explains some of the methodology behind it, why these new findings matter for decarceral policymaking, and where public health research in this area should be heading next. These insights, as shared with Inquest editor Cristian Farias over Zoom on Dec. 3, have been edited and condensed for clarity.

People sometimes think of detention facilities — prisons and local jails — as being out of sight and out of mind, and therefore concluding that our system of incarceration does not affect them. They may think it’s just affecting people who are incarcerated.

There are two huge problems with that line of thinking. One is that these are real people who are being exposed to inhumane, potentially life-threatening conditions, and when we think of public health, that includes everyone. Our nation’s health is only as good as the health of the most vulnerable people in our country. And the second issue is that the negative health effects of incarceration aren’t just limited to the people who are incarcerated. There is a growing body of evidence showing that mass incarceration has these spillover effects that extend beyond people who are directly exposed to the system — to people’s family members and to entire neighborhoods. Our analysis in this study zooms out one step further to see if these spillover effects are manifesting even at the county level. Could living in a county that incarcerates a lot of people have impacts on the overall health of the entire county? That is important to factor into our calculus of the harms that mass incarceration is creating — to look at it at a new level of scale. This is ostensibly a system that’s designed to keep us safe. But what if it’s actually making us all sicker and potentially making us die sooner?

This is ostensibly a system that’s designed to keep us safe. But what if it’s actually making us all sicker and potentially making us die sooner?

The intention with our follow-up study was to interrogate the linkage between jail incarceration and general mortality more to try to understand what are the specific causes of death that are driving that association. We also aimed to see if the findings from this study provided more evidence to suggest that the relationship we identified is causal and not due to some other spurious association, because there are certain causes of death that we would expect to be stronger drivers of this association based on the ways in which we know that incarceration impacts people’s health. That way, we can suss out: Are the patterns that we expect to see really showing up?

The idea for the original study showing a county-level association between jail incarceration and all-cause mortality was conceptualized by some of the co-authors of the study. I was able to work with them on this paper and lead the analysis. In terms of conducting the analysis, the first piece is just getting all of these large datasets together. The two main variables or measures in this analysis are, one, the exposure, which is jail incarceration rates at the county level on an annual basis; and then two, the outcome, which is county-level mortality rates. Both of those variables are collected and published through administrative data sets at the federal level. The Bureau of Justice Statistics compiles data on incarceration at the county level, and the CDC National Vital Statistics System reports mortality data. For this analysis, we used the Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends dataset, which provides cleaned data on jail incarceration at the county level.

Our goal was then to try to determine if a change in a county’s rate of jail incarceration was associated with a subsequent change in its mortality rate for specific causes of death. We also added some controls into the model to try to rule out potential alternate explanations. Since there are factors that might cause both high jail incarceration and high mortality, we wanted to control for those things to make sure that we’re ruling out those alternate explanations. Ultimately, we found that when a county’s jail incarceration rate increased, that was associated with a later increase in county mortality rates for all of the nine causes of death that we looked at — cerebrovascular disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetes, heart disease, infectious disease, malignant neoplasm, substance use, suicide, and unintentional injury. Among these nine causes of mortality, we found that jail incarceration had the strongest association with deaths due to infectious disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, substance use, and suicide. Understanding those specific causes of death helps us tease out what are the potential mechanisms that might be driving this association.

We found that when a county’s jail incarceration rate increased, that was associated with a later increase in county mortality rates for all of the nine causes of death that we looked at.

We also looked at different “lag times” — meaning the incarceration exposure data preceded the mortality outcome data by either one year, five years, or 10 years. This gets at short-term, medium-term, and long-term associations between county-level exposure to incarceration rates and mortality. We found that associations for causes of death where the time to death is typically shorter, as in the case of infectious disease or suicide, the associations decreased pretty quickly over time, which one might expect. By contrast, associations for causes of death that have generally longer latency periods, like heart disease, remained fairly steady as the lag increased.

These findings demonstrate that the causes of death that are the strongest drivers of the jail incarceration-mortality association are tied to psychosocial and economic resource deprivation and concentrated community disadvantage. That may not come as a surprise, because we know that mass incarceration criminalizes poverty, breaks social ties, and redirects resources away from social and public health services. So it makes sense that high levels of incarceration would make us all sicker, and also disproportionately impact communities that have already faced concentrated disadvantage in other forms.

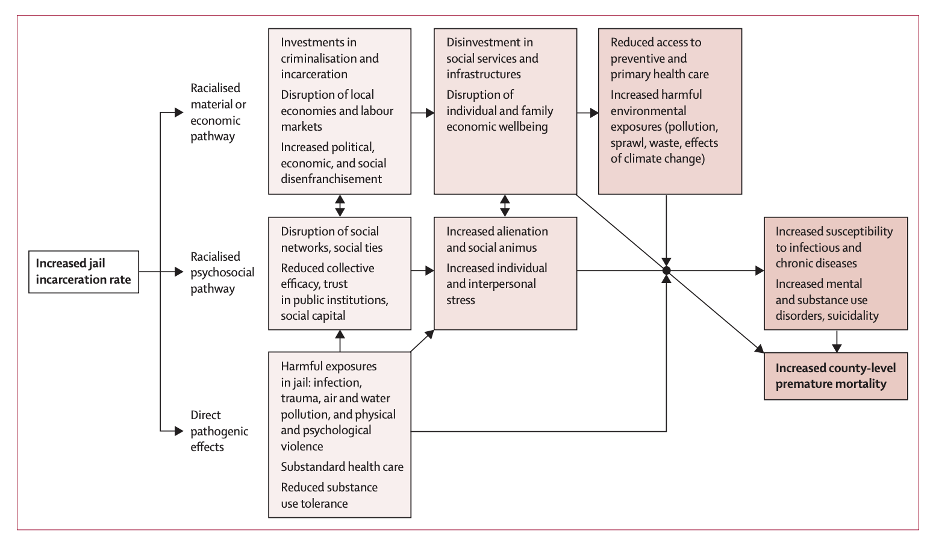

What we’re getting at is not just the direct health consequences for someone who is incarcerated themselves. We are also getting at potential spillover effects into the entire county. In our paper, we propose a conceptual model that spells out the pathways that we believe are explaining this association. How does living in a county with a high jail incarceration rate affect the health of that entire county?

We break it down into three different pathways. When you incarcerate a lot of people, the health of those specific people will be negatively impacted through a variety of harmful exposures. That direct effect is one pathway. The other two are more indirect, thinking about the health of the county overall; these are the psychosocial and material, or economic, pathways. The former is the effect on communities of forcibly removing people from the community, and then cycling them back into the community and potentially removing them again — that sort of revolving door of incarceration that’s expected to have really harmful psychosocial effects on the entire community because you’re preventing communities from building social networks and social capital — and sowing distrust within communities and feelings of stress and lack of safety.

The material and economic pathway operates at macro and micro levels. At the more micro level, incarcerating people extracts a lot of resources from the community through fines and fees from families and community members. It also makes it difficult for people to find and retain jobs, so people are being removed from the labor force of a given county. These processes are expected to have economic consequences, which we know affects our health. Then at the more macro level, we’re thinking about large scale investment or disinvestment in communities. If a county is choosing to invest a lot of its resources in incarcerating people as a response to social problems, that’s coming at the expense of investment that could go to social service infrastructure or public health infrastructure.

There is existing evidence that shows that living in a neighborhood with high prison rates is associated with poorer health for residents. And this research has also shown that this effect seems to be stronger among Black residents of a neighborhood compared to white residents. So exposure to mass incarceration is likely contributing to and exacerbating racialized health disparities. We might expect the same to be true for exposure to jail incarceration at the county level, where Black residents in a county with high jail incarceration may experience worse health effects compared to the white residents in that county. That’s something we want to explore but were not able to in this study, because, unfortunately, the race-stratified mortality data at the county level aren’t available at the level of detail that we would need.

One other limitation of this analysis is that because data are suppressed when a county has very low mortality counts to maintain anonymity, we had to restrict our analysis to counties that had complete enough mortality data. And so, as a result, our sample is skewed towards larger, non-rural counties. So, we’re looking at about 1,000 counties as opposed to the 3,000-some total counties in the U.S. Overall, high rates of jail incarceration have been shifting to rural counties. So, I’m curious to see how these associations and relationships might look within rural counties.

Policymakers should view decarceration as a strategy that is expected to improve health at the population level.

These findings really underscore the impact that jails have on infectious disease spread and potential mortality across entire counties. It drives home the point that correctional facilities aren’t contained environments; they’re part of our environment and our community. An outbreak of COVID in a jail is not going to stay in a jail. It’s that thinking, even beyond the context of COVID, that should be applied to the way that we think about incarceration. We know that jails have harmful health consequences at larger levels of organization, whether it be through material and economic pathways, or through psychosocial pathways. Thus, policymakers should view decarceration as a strategy that is expected to improve health at the population level.

More broadly, this is just one study among many creating a strong body of evidence to show the public health harms of incarceration. If we’re thinking about ways to improve safety and well-being, which is theoretically what the criminal legal system is designed to do, in a way that includes population health, then we have clear evidence that jails actually threaten our safety, rather than keeping us safe. We tend to think about safety in criminal legal terms like recidivism and short-term safety, but we often don’t think about public health consequences as an important element of safety and well-being.

Image: Unsplash