Over the last twelve years as a Colorado public defender, I’ve handled thousands of cases, representing clients with charges ranging from petty theft to gang-motivated homicides. I was called to do this work. I feel it in my core. I still remember the high from my first “not guilty” as a young lawyer and the sob I could not suppress when a teenage client received a life sentence. These are moments that will stay with me forever.

It’s hard to articulate the promise of Gideon. As a public defender, I have made countless promises to myself. In defeat, I promised I’d work harder. In triumph, I promised to continue the long hours and frantic pace, so I can keep helping people. I’ve also made countless promises to my clients, which I offered with sincerity and the best of intentions. But as an individual public defender, I could not keep all my promises and my sanity. I know of more than one promise left unfulfilled.

I’ve had a shift in how I see my role as a public defender. I no longer expect our greatest victories to be won inside of a courtroom. Rather, the future of public defense lies in unionized collective action, and the leverage it will afford us to demand true systemic change. Building strong public defender unions is how we can win both for our clients and for ourselves as workers.

A few years ago, I represented a middle-aged woman on a minor drug offense. Initially she was released by the court to remain in the community, but after several instances of not appearing in court, she ended up in jail pending trial. At the time, I considered her case “small potatoes.” I was representing a multitude of clients, and many were facing decades in prison. I felt certain that the prosecutor would offer her a misdemeanor plea bargain with a probationary sentence.

This essay is from the series

Beyond Gideon

A collection of essays examining how—or whether—public defenders can meaningfully contribute to the end of mass incarceration.

When I presented the plea option, she scoffed. “That cop is lying,” she replied. “I’m not pleading to shit.” We set an evidentiary hearing. I promised to visit her again soon—which I meant, but I didn’t follow through. Three weeks passed before I visited her again. It’s not that I didn’t want to visit her, I just had dozens of other cases. While she sat in jail, my time passed in a blur of hearings, motions, trials, and sentencings. Overburdened is a synonym for public defender.

The night before my client’s evidentiary hearing, I pulled out her file and realized there was an unreviewed video from the police officer’s body camera. I sighed, exhausted, and hit play. Ten minutes in, I gasped. The following morning, the prosecutor agreed to dismiss the case. My client had been right about the cop lying. In the police officer’s report, he described the baggie being in plain view, but the video showed him rummaging through a closed backpack.

I told my client we were lucky that this prosecutor agreed to dismiss the case. My client blinked slowly and repeated, “Lucky?”

My cheeks still burn with shame as I write this. She sat in custody for thirty-three days. I sat on a golden ticket for thirty-three days. Relative to sentences I’ve witnessed courts impose, thirty-three days is just a drop in a vast well, but consider what can happen in thirty-three days: A person can lose a job, fall behind on rent, miss a critical medical appointment, have children taken by social services. It is more than enough time for a life to unravel. Custody has many consequences, which quickly snowball for the indigent.

As public defenders we are often forced to push our limited resources to the most serious cases, but there is no such thing as a “small potatoes” case. The promise of Gideon is not scaled. This client deserved the same time and attention as a client accused of homicide—but that is not what she got.

I knew I wasn’t the only culpable party. There was the dishonest cop, the prosecutor who charged the crime regardless of the lies in the police report, the harmful bail system, the criminalization of addiction, and decades of failed drug policy. Yet I couldn’t escape my guilt and shame. If only I had worked harder and looked into the file sooner, I could have prevented a month in detention. In retrospect, I question whether my mistake was failing to keep my promise, or making the promise in the first place, given the realities of the unyielding workload and corrupt criminal system.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

As public defenders, we often internalize the David-and-Goliath idea that the small but righteous can overcome the mighty. Sure, the workload is overwhelming, but a good public defender—a David public defender—can slay Goliath if she just works harder, stays in the office later, sleeps less, and writes one more motion. The culture praises the individual defender who works all night prepping for a trial or who spends all Sunday doing jail visits.

Most of my career, I embraced the role of the individual hero. It has cost me. The toll of the constant stress and long hours (still never enough) on my health, well-being, and relationships is undeniable. There is also a real cost for our clients. Doesn’t my client deserve timely preparation rather than gas fumes? Am I really Gideon’s promise when I only have time to visit my client the night before docket?

Possibly the hardest truth any public defender faces is the realization that the criminal system is propped up by our best intentions. We get into this line of work because we are helpers by nature, fighting to get justice for society’s least-supported individuals and communities. Yet without our participation tacitly sanctioning the criminal “justice” assembly line, the system could not continue its inhumane march. The Constitution demands effective representation—but the realities on the ground make a sad mockery of that promise.

It’s time to shift the narrative. I am not David. I can’t be David. A single well-intentioned public defender cannot defeat the myriad problems inherent in our racist, classist criminal processing system. We have to stop asking individuals to be heroes. Our efforts are better spent organizing a collective, which stands a chance of having the power and traction to address larger systemic issues.

In February 2022 I was part of a small group of Colorado public defender employees who started to organize around the possibility of building power. There had been whispers of trying to unionize in the past, but the lack of Colorado state laws explicitly authorizing public-sector unions had deterred earlier attempts.

The first meeting I attended, there were six of us. I was on the couch with my cat, sipping a glass of wine, trying to position my phone to hide my frumpy pajama pants. I was skeptical but excited. We had intense conversations: How many is too many cases? What happens to the clients not represented by the PD? How can we make this a career where people stay instead of burning out in five years?

My second union meeting, there were twelve people present. By the third meeting, we were spreading like wildfire. I wasn’t alone with my guilt. Coworkers from every job classification shared similar examples. We were creating a space where it was OK to be vulnerable. Speaking honestly about clients we’d failed led to a raw assessment of what needed to change. We decided to call ourselves the Defenders Union of Colorado (DUC). DUC represents employees wall to wall—administrative assistants, investigators, paralegals, social workers, and attorneys.

For decades unions have propelled some of the greatest workplace improvements across the United States. Weekends, workplace safety, minimum wage, and child labor laws came out of the organized labor movement. Why not unions in public defense?

Colorado’s public defender system is often cited as a national exemplar, but we aren’t immune to the pervasive and systemic challenges in public defense. One of the largest goals identified by DUC was moving our system toward workload caps. Excessive workloads and unsustainable working conditions are punishing our clients and us. Our clients receive inadequate and, indeed, constitutionally ineffective assistance—and as workers we bear the physical and mental toll until even the most devoted burn out and leave.

Unionizing can give us the tools to demand systemic change. In every courtroom across the United States, court-appointed counsel represent the vast majority of criminal defendants. As public defenders we are not “fighting the system”—we are the system. We are indispensable—and because of this we have power. It just needs to be harnessed.

It’s been sixty years but collectively we still have a long way to go. The promise of Gideon mustn’t take the form of public defenders promising to sacrifice the little we have left to give as individuals. Rather, the promise should be a commitment to work together to change the system through unified action.

In September 2022 the Defenders Union of Colorado went public as a proud affiliate within the Communication Workers of America Local 7799. While there are jurisdictional differences across the state, we share the same frustrations, exhaustion, numbness, and desire for change.

DUC aims to achieve workload caps; a livable wage; skill pay for bilingual and other value-adding staff members; improved leave policies and relief from a workaholic culture; improved justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion policies; strategic input in budget, planning, and legislative advocacy; meaningful review of supervisors; better training; and more avenues for career growth. Our mission is to improve service to all our clients and working conditions for all our members. These goals go hand in hand. Only by fulfilling them can we truly keep Gideon’s promise.

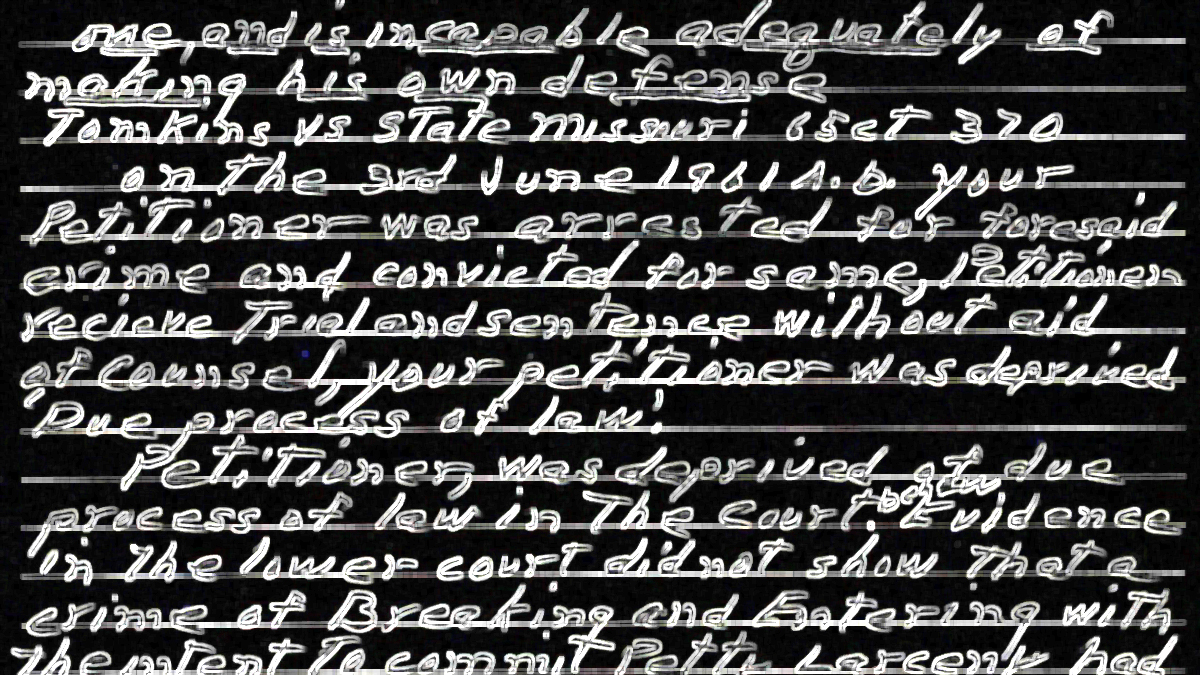

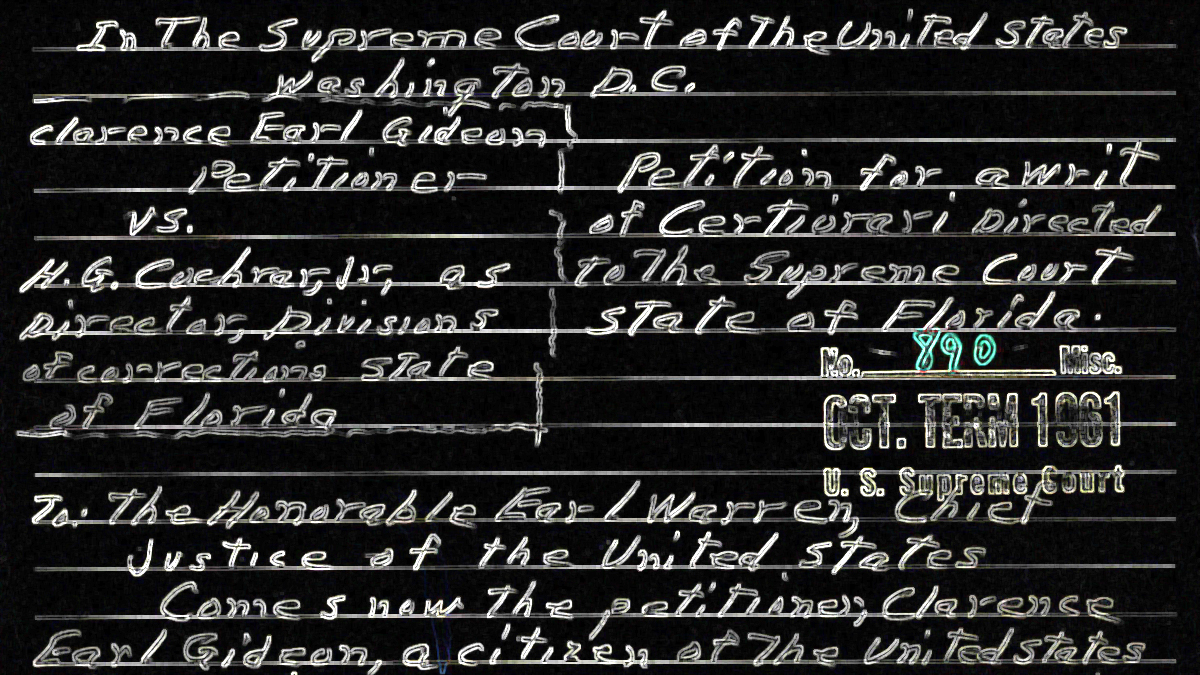

Image: National Archives/Inquest