In the fall of 1972, the men incarcerated at the state prison in Walpole, Massachusetts, organized themselves into a labor union, the National Prisoners Reform Association (NPRA). Soon after, in March 1973, MCI-Walpole’s guards went on strike to protest the appointment of a progressive state commissioner of correction, John O. Boone. The NPRA took over the prison and ran it peacefully for two months. Seizing on the opportunities provided by the guards’ strike and by Boone’s appointment, the men incarcerated in MCI-Walpole launched an extraordinary struggle for self-determination and an important chapter in the movement for prison abolition.

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the prison takeover, a broad consortium of participants (including members of the NPRA, colleagues of Commissioner Boone’s, and civilian observers) gathered at Harvard University for two days of conversation in the company of several Boston-area decarceral organizations (including Inquest’s parent organization, the Institute to End Mass Incarceration).

In this feature, we reflect on some of the key lessons that emerged from these discussions between a new generation of abolitionist activists and those who lived through the events at Walpole. Video links are included for readers who wish to directly access some of the reflections and insights shared at this unique gathering.

3000 Years and Life, a documentary filmed by Randall Conrad and Stephen Ujlaki during the takeover, offers a unique glimpse of MCI-Walpole running under the direction of the NPRA. (The entire film can be watched on YouTube.) When planning the Walpole event at Harvard, we chose to start by screening the film because we knew that many people in attendance had very limited knowledge of what had happened at the prison, and the film immerses the viewer in that time and place.

The screening was attended by several people who had intimate knowledge of the 1973 events, including Bobby Dellelo (the first president of the NPRA), Albert Brown (a member of the NPRA Board of Directors and of Walpole’s BANTU—Black African Nations Toward Unity), and the Rev. Edward Rodman (a leader of the NPRA’s outside supporters). Together, Dellelo, Brown, and Rodman reflected on the film in a discussion moderated by Keith Harvey, Northeast regional director of the American Friends Service Committee.

During this conversation, Brown discussed the impact of Dellelo’s and NPRA Vice President Ralph Hamm’s leadership:

They were heroes for a lot of us, because one thing Bobby and Ralph did was they kept us safe. . . . Safe from who? Our selves, the administration, and other elements.

Dellelo emphasized how the NPRA’s programming, with its emphasis on education and collective betterment, differed drastically from the prison administration’s approach:

We know how to rehabilitate people. They [the prison] don’t have a vested interest in rehabilitating prisoners—it’s job security. It’s that simple. That’s the problem. We have to abolish the prison system.

Crucial to this success, Brown noted, was the NPRA’s incorporation of incarcerated peoples’ families in all of its programming:

Every program that was put together included family. So, your families could come in and participate. . . . My mother gets to meet your mother, my sister gets to meet your sister. . . . Your families are the people who have got your back, who care about you the most, who look out for you.

The NPRA knew that opening up Walpole to the eyes of the public was essential to their success. During the takeover, the Observer Program, called for by the NPRA and organized by outside supporters, played the essential role of providing a view of the prison’s operation unmediated by the administration. Rev. Rodman, joining the discussion remotely, described the Observer Program’s mission:

The main thing that was motivating us was a desire to support the prisoners and to be visible so that, hopefully, everybody would be on their good behavior. And that was the case for the majority of the time that we were in there. It was amazing to me that the discipline that they showed was contagious. . . . Fundamentally, empowering the prisoners to truly be self-determined—that was, I think, our major contribution, supporting them in doing the things that they wanted to do but had been denied.

In 1972 men incarcerated in Walpole founded the Black cultural and political organization BANTU. The symposium at Harvard was able to reunite a number of people who’d been involved with the organization, including former BANTU member Albert Brown, David Dance (an undergraduate supporter of BANTU in 1973), Jabir Pope (a member of the Concord Prisoners’ Peaceful Movement Committee at the time of the Walpole takeover), and community activist Kazi Toure. (In 2021 and 2022, respectively, Pope and Brown were exonerated after serving decades together under a wrongful conviction for a 1984 murder.)

In a conversation with renowned civil rights attorney Margaret Burnham, they emphasized similar lessons about education, self-reliance, and a vision of rehabilitation. Brown described how Black men in Walpole organized themselves through BANTU to provide education, explore cultural identity, and build unity. “Walpole was a very dangerous place,” he explained, especially for Black incarcerated men, who constituted only 10 percent of the institution’s population at that time. “We had to get together to survive.” Brown also detailed the resistance they encountered from Walpole’s administration when they called for educational opportunities:

Their answer really was: ‘We’re about security. You want programs, you all are going to have to do it.’ And that’s exactly what Ralph and Bobby and we all did.

Pope spoke from his experience of incarceration at MCI-Concord during this same period. He echoed Brown’s account of developing programing within the prison and in spite of the administration. Pope explained that prison reform legislation passed by Massachusetts lawmakers in the wake of the Attica uprising

provided us with a mandate for rehabilitation. The mandate went as far as to say that if the DOC failed to rehabilitate us, that we had the right to rehabilitate ourselves. And so that was the spirit under which [BANTU’s] Peaceful Movement Committee was formed, and that’s what we strived for.

Pope also emphasized the importance of political education in the group’s efforts:

The Peaceful Movement Committee was about the business of educating prisoners through politics—because a lot of people don’t realize that, as prisoners, politics hit us first, before it moves on to the general population.

Toure echoed the importance of family to inside organizing. His brother Arnie King was incarcerated at Walpole in 1973, and Toure became involved with Family and Friends of Prisoners:

We rode the bus out to different prisons, did vigils, stood outside the prison, organized people to be out there to witness what was going on inside, to make sure that they didn’t harm our people too much.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

In remarks made during the symposium, Burnham helped to situate the remarkable accomplishments of BANTU and the NPRA in relation to the systemic reforms being undertaken by the radical administration of Boone, the state’s first Black DOC commissioner:

But for Sargent and Boone, we never would have had furloughs, we never would have had educational programs in those prisons, we never would have had expanded visitation, we never would have had the limited due process that we ultimately did get for folks who were locked up in segregation. All those things came because of the united efforts of the folks pushing behind the bars . . . and the leadership. And [Boone] had to deal with not just the righteous and rightful demands made by the prisoners but, as well, he had to situate himself between the political leadership at the statehouse down in Boston [and] the guards’ union [at] a period of time in which the guards all across New England were feeling their muscles as workers.

Boone’s top-down push for reform, as well as his willingness to work with and support incarcerated leadership, converged with the NPRA’s bottom-up push for change.

During the symposium, a number of people spoke of the Boone era and its aftermath, including Dellelo, former Massachusetts Department of Health and Human Services advisor James Isenberg, former Walpole guard Tony Van Der Meer (now a senior lecturer in Africana Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston), and former Massachusetts Parole Board chair and retired judge Paul Chernoff.

Dellelo described vividly how the Walpole prison guards, by going on strike, sought to undermine Boone’s leadership by triggering another Attica-style massacre: “When the guards went out, what that was about was they were looking for a bloodbath: blame Boone and throw him out. They used to carry cards that said ‘KKK’.” Knowing this, the founders of NPRA sought to organize themselves into a force that could counter the guards:

The main thing that we wanted to do with [the NPRA] was to create a union . . . because as a union, we could challenge the guard’s union and pull the unification away from them. We could force them to behave themselves.

Dellelo also made clear the role that Boone played in helping make the NPRA’s organizing successes possible:

He used to do everything we wanted him to do. He was, like, on our side. And you had to join him—you didn’t have a choice. . . . Boone, I had all the respect in the world for him. He was real. That was the main thing, when he said something, it wasn’t bullshit. This was a guy who was talking right out of his heart.

Isenberg, who at the age of twenty-six had been tasked with finding the state’s new commissioner of corrections, described his first encounter with Boone in 1971 at the Lorton Penitentiary outside Washington, D.C., where Boone was superintendent prior to coming to Massachusetts:

And then I walked in the prison with him, just the two of us. And he walked through the prison, and I’ll never forget—all the men would just [salute]: “Mr. Boone,” “Mr. Boone,” “How are you, Mr. Boone?” He was respectful and they were respectful. And he had the first program going where guys in Lorton were going to community colleges. . . . He was doing things that hadn’t been done anywhere.

Chernoff noted the importance of Attica as crucial context for Boone’s appointment:

The one thing John had going for him—and we don’t have it now—was that Attica had just happened and so there was a willingness to try to open things up. . . . It had never happened before—you wouldn’t get a John Boone into the Department of Corrections—and it hasn’t happened since.

Van Der Meer drew on his experiences as a guard at Walpole a few years after the takeover and Boone administration, as well as his many years as an activist in the Boston area. He underlined the importance of building support for restorative justice programs both in prisons and in the communities to which incarcerated people will return. This kind of community organizing work, Van Der Meer argued, should be informed by the bottom-up organizing practiced by the NPRA:

Hopefully, we can learn from the Atticas, the Walpoles. But it’s on all of us in terms of: what society do we want, and what are we going to do in terms of bringing about that change? . . . If we’re not trying to work with the people who are most impacted, we’re not going to create the kind of changes that we need.

The symposium included a number of moments when activists from younger generations were able to reflect on how the example of the Walpole takeover spoke to today’s prison abolitionist movement. Joining the conversation were Andrea James, Tone the Organizer, and currently incarcerated activists Corey “Al-Ameen” Patterson and DuShawn “Duke” Taylor Gennis, who participated via recorded statement.

In MCI-Norfolk, another Massachusetts state prison, an organization called the African American Coalition Committee (AACC) follows in the footsteps of Walpole’s BANTU. Patterson, the AACC’s vice-chair, discussed the centrality of Black culture to abolitionist action:

I believe that any type of abolitionist work—any type of work around trying to combat or reform the criminal legal system—has to embody Black culture. Because Black culture is not just about changing something, it’s about surviving and prospering.

Describing the work of peacemaking and political education that AACC carries out in MCI-Norfolk, Patterson explained:

It’s a beautiful, beautiful sight when you can actually see two individuals that once had this intense rivalry to each other actually squash that and really see the workings of structural racism really being the cause of their problems and beefs in the first place.

Burnham reflected on the takeover’s lessons for abolitionists today, calling for nuanced analysis and rigorous debate within the abolitionist movement. She cautioned that distinguishing “abolitionist” from “reformist” policies may not be as straightforward as some assume:

We need to think very carefully about this notion that there is a rigid, strict, and easily identifiable line between so-called ‘reformist’ reforms and ‘revolutionary’ or ‘abolitionist’ reforms. I don’t think that line is as clear as people want to make it. And I think the more we realize how fragile or how easily manipulable that line is, the better off we all are. So let me just ask you, for furloughs in the 1970s: Is that reformist reform or is it abolitionist reform? Education at Boston University: Reformist or abolitionist? Higher pay for guards: Reformist or abolitionist? Better training for guards: Reformist or abolitionist? Now, we can argue all this and we should . . . but this is not a question of just one basket of eggs over here and another over here, and if you’re not in my basket, well, you’re not an abolitionist. I don’t think it’s that simple.

Tone the Organizer offered thoughts on how abolition can and must have many definitions, informed by many different perspectives:

I want to make sure people are very clear. . . . There are many definitions of abolition. And the type of abolition I understand is not just dismantling, but reimagining and creating. So it’s active. . . . You have to stand up. The reimagining part is: OK, this always continues to happen until you (and the ‘you’ is: look in the mirror!) do something differently.

Speaking from the perspective of an earlier generation and as a leader of outside support efforts for the NPRA during the Walpole takeover and beyond, Rev. Rodman reminded the audience of the need for maintaining hope in order to sustain action over time:

Maintaining that energy, that commitment, is the key to the whole thing. If we cannot ‘keep hope alive’ . . . then we are not going to be able to achieve this goal. We have to stick to it, we have to keep our energy and hope up, and, most importantly, we have to believe that it can be done.

When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: 50 Years Later was co-organized by Jamie Bissonette Lewey, Toussaint Losier, and Thomas Dichter. Hosted by the Mahindra Humanities Center, the event was co-sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee – Northeast Regional Office, the Committee on Degrees in History & Literature, the Edmond & Lily Safra Center for Ethics, the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, the Harvard Prison Legal Assistance Project, the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, the Inequality in America Initiative, the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, the Mindich Program in Engaged Scholarship, the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, and the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass Amherst.

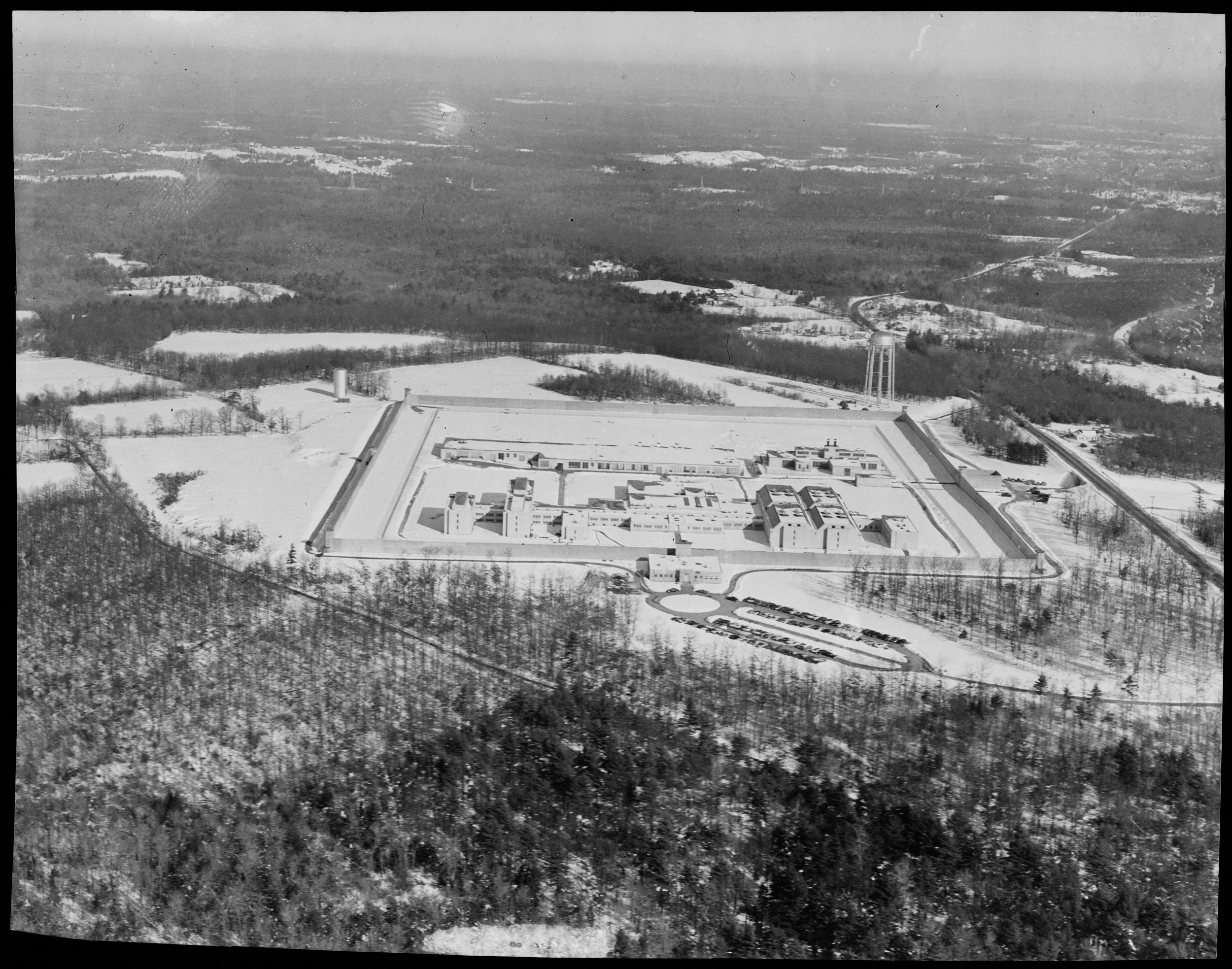

Image: Boston Public Library/Massachusetts Collections Online