The outpouring of public support for Luigi Mangione, the man accused of killing UnitedHealthcare (UHC) CEO Brian Thompson, has been truly exceptional. This reaction cannot be put down exclusively to his looks, or even a collective hatred of private health insurance companies—a unifying position for many Americans. The government’s legal case against Mangione is exposing the workings of the U.S. criminal legal system for what it truly is: an enforcer for white capital.

The U.S. economy works to concentrate money in the hands of the wealthiest, who are disproportionately white, and out of the hands of the poor and people of color. This is reflected in the health-care industry, which has become an integral part of U.S. capital. Health care is the largest individual sector of the U.S. economy. Within this industry, UnitedHealthcare is, by revenue, the largest health-care company; it is the eighth largest company in the world by revenue. These insurance providers have proven extremely profitable to their shareholders, with UHC’s stock price alone rising by nearly 1,727 percent since 2010. When it comes to accessing health care, this for-profit system that so enriches those at the top serves to impoverish and sicken those with the least proximity to wealth and whiteness.

It should come as no surprise, then, that when this system is threatened, the criminal legal system works to support it by targeting, surveilling, incarcerating, and killing a population that is disproportionately Black and almost exclusively poor, while at the same time working to protect and insulate the interests of the wealthy and white. Mangione, a white, Ivy League–educated cisgender man from a background of considerable wealth and privilege, may seem an odd figurehead for this message. But it is actually, in part, his ordinarily protected background that allows us to more clearly see the true aims of the criminal legal system.

For what is, at its core, a straightforward murder case, the charges against Mangione are exceptional. He initially faced twenty charges across three jurisdictions—New York, Pennsylvania, and the federal government—with some replicated at both the state and federal levels. Mangione’s defense lawyer, Karen Agnifilo, described the federal charges (brought in December 2024 by then–attorney general Merrick Garland, after state charges had been filed) as “unprecedented prosecutorial one-upmanship,” noting that simultaneous prosecutions of this sort are highly unusual. Yet current attorney general Pamela Bondi has not only upheld but escalated her predecessor’s decision, announcing in April that federal prosecutors plan to seek the death penalty. The message is clear: the murder of individuals like Brian Thompson will not be tolerated.

It is important to understand that the workings of the criminal legal system are bipartisan, and not a case of Republican tough-on-crime overreach. The New York state charges are being brought by Alvin Bragg, a district attorney often accused by the right of being a “progressive prosecutor.” Federally, while this case is now being prosecuted by a Republican Department of Justice, the death-eligible charge was first brought by Attorney General Garland, a Democratic appointee who was no doubt aware that the incoming administration was likely to overturn the federal moratorium on the death penalty. Both parties work in the interest of white capital.

When we look at other high-profile murder cases, it becomes clear that the criminal legal system has responded to Mangione’s alleged crime with particular severity. Consider, for example, former U.S. marine Daniel Penny, who killed Jordan Neely, a homeless Black man, by choking him to death on a New York City subway in May 2024. Penny claimed that he was acting to protect his fellow passengers from Neely’s erratic behavior, and in the end—despite full video documentation by fellow passengers, which shows Penny holding Neely in a chokehold long after the latter had stopped moving—the jury agreed. Penny was declared not guilty of criminally negligent homicide the same week that Mangione was arrested. (The more serious charge against Penny of manslaughter had already been dismissed by the judge.) Both men made the front page of the New York Post on December 10: Penny’s smiling face, plastered above the headline “Enough is Enough: Jury Rejects DA Bragg’s indictment of man who protected subway riders,” appears next to a sidebar about Mangione, reading “Target: CEOs. Revealed: Chilling manifesto of health insurance boss ‘killer’.”

Penny’s case is not unique, but rather repeats the same pattern we have seen again and again. White vigilantism is regularly forgiven if it comes at the expense of the poor and people of color, or is committed by those representing the interests of white capital. This was clear in the case of Kyle Rittenhouse, who was found not guilty of murder after using an illegally purchased semi-automatic weapon to kill two people and injure a third at a Black Lives Matter protest. It was clear, too, in the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who chased down, shot, and killed seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin while the teenager was out for a walk.

Such impunity is also almost unfailingly extended to police. One of the most recent examples is the case of Timothy Johnson, who was shot and killed by a Virginia police officer who suspected him of having shoplifted two pairs of sunglasses from a Nordstroms. The officer chased Johnson out of the mall and into a nearby wooded area before shooting him in what the officer claimed was self-defense. Johnson was unarmed. Unlike many similar instances of fatal police brutality, this one made it to court. The officer was acquitted of involuntary manslaughter but found guilty of reckless handling of a firearm and sentenced to three years in prison. But even this rare attempt at accountability did not last long. Within days of the conviction, Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin stepped in to announce that he was pardoning the officer. When announcing the pardon, Youngkin stated, “I am convinced that the court’s sentence of incarceration is unjust and violates the cornerstone of our justice system—that similarly situated individuals receive proportionate sentences.” The question is, who does Youngkin consider “similarly situated” to this officer? If he is referring to other police officers who have committed murder, then he’s exactly right: holding a police officer accountable for the murder of an unarmed Black man does indeed violate the rule of police impunity.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Of course, we can’t make a one-to-one comparison between Mangione’s case and those we’ve been discussing; his trial has yet to even be scheduled. But the charges against him, and sentences sought, already make clear that the criminal legal system’s response to murder has everything to do with who is murdered—and who does the murdering.

There was clear, undeniable video evidence that showed Penny and Rittenhouse killing other people. Yet in Penny’s case, the legal system also validated Penny’s claim that a poor Black man represented a threat to those around him. And while Rittenhouse’s victims were all white, they had been attending Black Lives Matter protests, and Rittenhouse’s claim that he was present in order to help protect businesses clearly resonated with the Wisconsin jury who had spent the previous several months absorbing media that portrayed these protests as violent Black mobs. Other supporting examples abound. In the murder of Timothy Johnson, the state stepped in to make very clear that it was reasonable for them to be murdered for the crime of potentially having stolen from a department store. And we would be remiss to not include George Zimmerman in this list: when, in 2012, he killed unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin, Florida’s Stand Your Ground law provided him with the perfect legal defense.

But in response to the killing of a health insurance CEO, a representative of white capital, the legal system is being wielded to its full extent, and with an eye toward spectacle. Only Mangione was publicly perp-walked, surrounded by heavily armed NYPD officers, the police commissioner, and Mayor Eric Adams. Only Mangione has been shackled at the feet, waist, and hands for court appearances. Only Mangione has been denied bail. Only Mangione has been threatened with the death penalty. The actions of Penny, Rittenhouse, and Zimmerman did not pose a fundamental threat to the established order. In allegedly killing one of the primary orchestrators and beneficiaries of white capital, Mangione’s did. These are not inconsistencies or loopholes in the legal system—this is exactly how it is supposed to work.

It would be overly simplistic to say that the cases discussed above demonstrate that murder is legal. Yet the ambivalence with which the criminal legal system treats the killings of those deemed inconsequential to people in power has long been documented. Perhaps even more damning is the absence of emergency about the vast number of excess deaths caused by the private, for-profit health-care system and insurance companies—deaths that bring the system increased profits. We can think of these systemic killings as examples of what Friedrich Engels called “social murder.” In his foundational 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England, he introduced the term:

When society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live—forces them through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence—knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains.

The constant denial of claims by insurance companies—and the consequent deaths of those unable to afford out-of-pocket medical care—are a crucial tactic used by health insurance companies to amass their towering profits. UHC, of which Thompson was CEO, has the highest claims denial rate (33 percent) of any major health insurance company. Under the tenure of Thompson, UHC began using an AI model to determine the approvals of certain patients which, according to the text of a lawsuit against the company, was known to “ha[ve] a 90% error rate.” The lawsuit alleges that the continued use of this tool was deliberate, “because they know that only a tiny minority of policyholders (roughly 0.2%) will appeal denied claims.” Given that UHC provides health insurance for 52.9 million Americans, the number of people who may have been harmed or even killed as a result of this policy is staggering. UHC and other health insurance companies quite literally depend on the suffering and death of a certain number of their policy holders in order to secure their high profits.

By comparing the case against Mangione to the state’s cases (or lack thereof) against other alleged murderers, I am not simply cherry-picking in an attempt to demonstrate that sometimes different cases have different verdicts. Instead, these comparisons offer a high-profile representation of how the U.S. criminal legal system works to protect and enforce the interests of white capital at the expense of all else. This reality is reflected in the demographics of who we imprison. With 2 million people incarcerated, the United States has the highest number of incarcerated people in the world, and the fourth highest incarceration rate after only El Salvador, Cuba, and Rwanda.These numbers do not include people on probation, pretrial release, or otherwise under some form of monitoring by the carceral system, which would add a further 3.7 million adults. Of those incarcerated and on probation, Black people make up 37 percent and 30 percent, respectively. Of those serving life sentences, 48 percent are Black.

What is also apparent is that the vast majority of people who end up in the criminal legal system started out poor. The Prison Policy Institute found that in 2014, “incarcerated people had a median annual income of $19,185 prior to their incarceration, which is 41% less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages.” This significant income gap between incarcerated and non-incarcerated people held constant regardless of gender or race, but was unsurprisingly exacerbated along those lines, with Black and Hispanic women making just $13,890 and $11,820, respectively, in the year before their incarceration, and white men making $21,975.

The criminal legal system works to enforce and protect the interests of white capital. In pursuit of this aim, it mainly arrests, surveils, imprisons, and executes its poor and racialized populations. While Mangione would not ordinarily be at risk of finding himself among these ranks, he has been accused of a crime so clearly threatening to those at the heights of white capital that the legal system seeks to make him both an exception and an example.

The high-profile nature of this case has helped expose the corrupt and exploitative nature of private health insurance to an even greater number of Americans. As public support continues to coalesce behind Mangione, it seems as though many are finally seeing the true nature of U.S. “justice.”

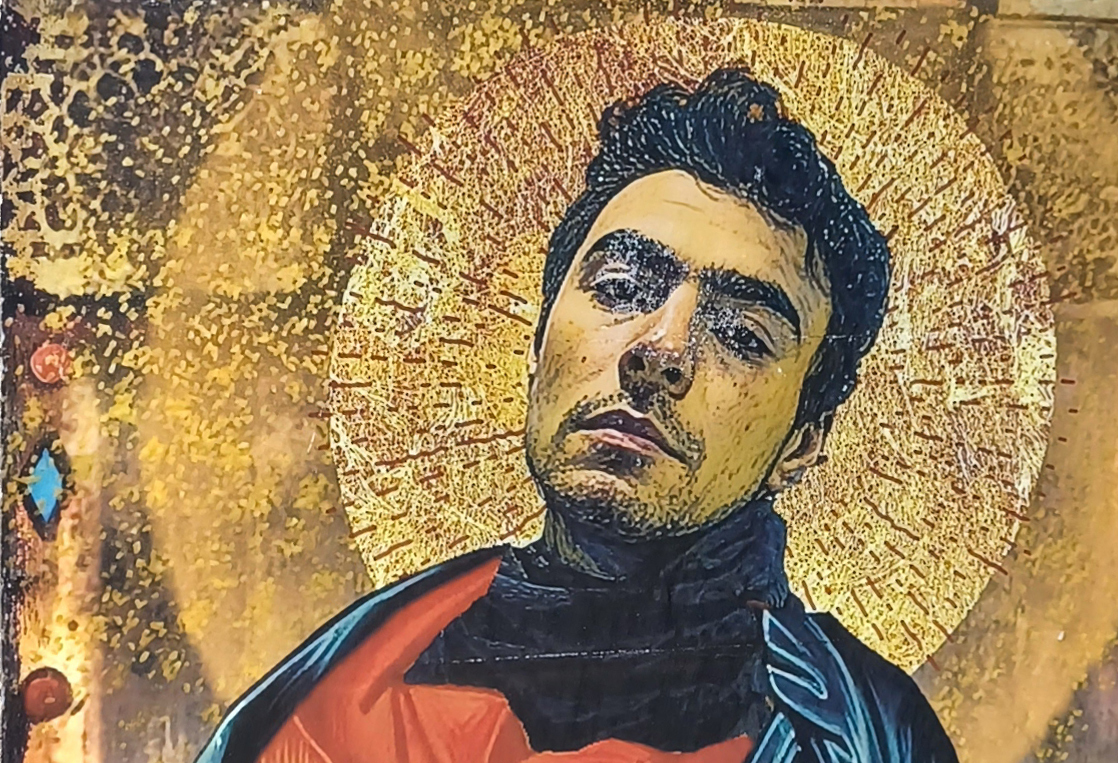

Image: Graffiti of Luigi Mangione found in San Francisco area. Photograph by Charles Lewis III. Licensed as CC BY-NC 2.0.