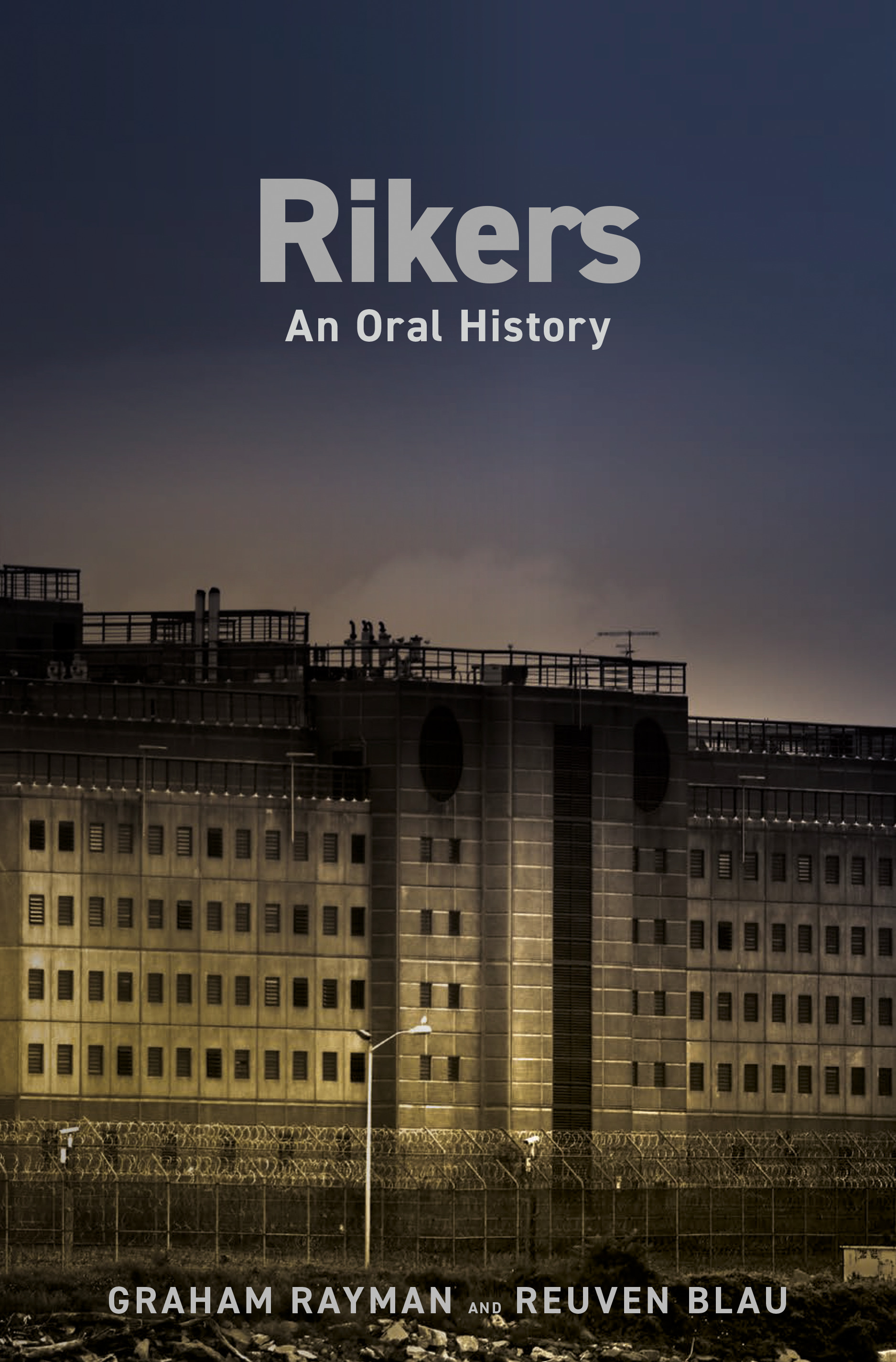

Rikers Island in New York City is home to one of the largest penal institutions in the world. Although designed for pretrial detention and shorter custodial sentences, the notorious jail complex is more like a long-term detention facility for people too poor to await trial with their freedom intact. As a result, many people languish there for years at a time.

When release day finally comes, the act of departing Rikers begins with “the pack up”—the assembling of possessions into a black plastic garbage bag—and then there’s a predawn wake-up call. And then waiting. And more waiting.

For those going “up top”—being sent to state prison—there’s a bus standing by. For the vast majority, though, upon their release they receive only a sheaf of forms, a $2.75 transit pass, and a ride on the Q100 bus to Queens Plaza. There, these Rikers survivors, garbage bags in tow, wait again for a connection home. The city’s Department of Correction offers no more than this to prepare detainees for their emergence from jail, even after long incarcerations.

In the following snippets of oral history collected by journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau in Rikers: An Oral History, people who were detained on Rikers recall their release day and what life was like after. A concluding reflection draws attention to the reality that for many, there is no leaving Rikers: In 2022 nineteen people died while incarcerated there, and countless more will forever carry with them the scars the jail complex left them with.

DONOVAN DRAYTON, detained 2007–12

The first day I got out of Rikers after five years, I got some food.

I remember telling my stepmom, she asked me on the phone, what do you want to eat when you first come home? I’m saying, I want some jerk chicken with some peas and rice and some sweet plantains and an ice-cold grape soda. Sure enough, when she came to pick me up, she had that pot of Jamaican food for me and that soda. I was eating that in the car. We drove back to the house.

I ate so much that night. I stayed up and I just watched TV all night. And I ain’t gonna lie. I cried, man. I cried like a baby. Like that night when it finally, finally settled in, I made it back. I feel that feeling sometimes still to this day. I made it, man. I just cried on my grandma and stepmother’s couch. I was just sad, I watched TV, and the Internet was on. I was listening to music. I’m like, yo, this is technology. Technology completely evolved in the five years that I was there, FaceTime and iPhones—like, you know what I’m saying?

My dad called me; I was up mad late. And we were just on the phone crying, like, we made it, bro. Thank you so much. I appreciate you, man. I don’t know where I’d be without you, big dog. Yeah. Wow.

Never forget the struggle, man. People forget about people in prison all the time. Thank God, he gave me a second chance to be here sitting talking to you.

I still to this day have moments where I get on my hands and knees and kiss the ground and just give God all the grace and glory because being free was a far distant memory at one point in time in my life.

DAVID CAMPBELL, detained 2019–20

My last thirty days—time really slowed down, and I had a tough time sticking to the routine that I developed to pass the time. It was a slog, but I made it through.

It was always kind of a gamble when they were going to pick you up from the dorm. And a lot of times it seemed to be between midnight and 2:00 a.m. on the day of your release. They also pick guys up as late as 6:00 a.m.

So about quarter to 1:00 a.m., I’m like, man, they’re not coming. I’m going to go to bed. As soon as I lie down, they tell me to pack up, coming for you at 1:00. I was like, fuck, yeah, 1 o’clock. In 15 minutes, I’ll be starting the process. I’ll be at intake, who knows how long that’ll last, but at least I’m getting the ball rolling. And so 1 o’clock comes, 1:15, 1:30, 1:45, 2:00, 2:15, 2:30. They’re still not there.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

I’m fucking bugging out. Every once in a while, I’d be like, “Can you call intake? Like, what’s up?” Like, you said be here at 1 o’clock. And the [correctional officer] is like, “They didn’t forget about you.” Finally, at 2:30, he’s going on lunch break. So he escorts me halfway down the hallway, with my big bag full of shit. Most guys take little to nothing home. I wrote like 40 legal pads. I didn’t want to send them home. So I had them all in a big trash bag. I had a French dictionary the size of a cinder block. I had a whole bunch of paperwork, and it’s just like dragging this big bag. He walks me about halfway down the hallway, and the lady that was supposed to pick me up at 1 is just chatting in the hallway to some other guard. That’s why she didn’t pick me up. She’s just chatting. It’s like, goddamn it, do you not know that these are the longest 90 minutes of my life?

You can’t wear your jail clothes out. And I had an outfit that I wore for court. The kiosk for your personal property is not gonna open till 5:00 a.m. You can wait until 5:00 a.m. I said, nah, just get me out of here. Like, I don’t want to be here another hour.

So they’re like, all right, well, we got to get some clothing for you. The CO goes and comes back with a tight salmon-colored hoodie. And it’s got a white and a black stripe on each sleeve. And then these skinny jeans that are distressed and they have holes in the knees, and it’s got a little tag on the bag. It says, “Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets.” Yeah. Supercool.

So that was my look. And I hadn’t trimmed my beard in months and my hair’s all wild. They put me on a bus with a guy who had done three days on a drunk-driving charge. And he was like, I did three days. I’m like, cool, I just did twelve months. That was the last guy I was with. We rode across the bridge together.

CASIMIRO TORRES, detained various stints 1980s–2000s

I had a girl one time, I used to go to this twenty-four-hour store after I came out of prison, late at night, and after a few times she started calling me Smiley. I said, “Why do you call me that?” And she said, “Because you’ve never smiled.” And it had never occurred to me that I hadn’t smiled in years and years. I had my prison face on wherever I went.

COLIN ABSOLAM, detained 1993–96

The different sounds of prison, like keys jingling, bother me [to this day]. I have my own keys, and when I go to open the door, they jingle, and that does something to my mind because that’s something I’ve been used to hearing for a long time.

SOFFIYAH ELIJAH, Executive Director of Alliance of Families for Justice

I was on a panel with Kalief Browder’s mother, Venida Browder. [In 2015 twenty-two-year-old Kalief died by suicide after spending three years on Rikers—including two years in solitary—for allegedly stealing a backpack.] And we were sitting side by side during the panel where she was trying to speak about her son’s suicide, and she reached under the table and reached for my hand. She gripped my hand so tight it hurt. There’s no other way to put it. I couldn’t think about doing anything except to hold her hand as she tried to explain that experience.

And about six months later, she was gone [from a heart attack]. I always remember that. Even as she was speaking on the panel, how did she find that strength to share it with people? I remember thinking to myself, there’s got to be something internal that we never, ever heal.

From the book RIKERS by Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau. Copyright © 2023 by Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Image: iStock/Inquest