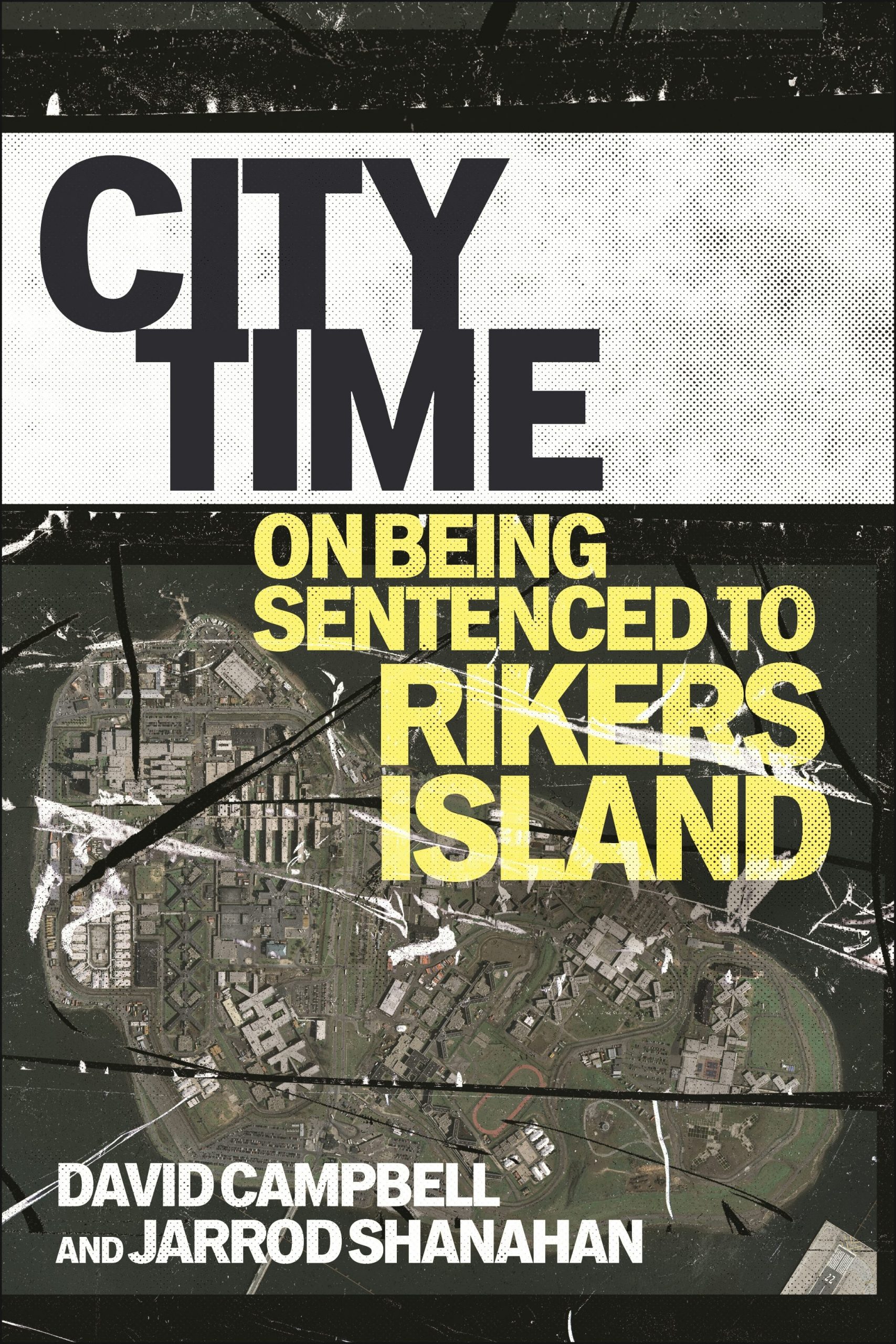

City Time: On Being Sentenced to Rikers Island

David Campbell and Jarrod Shanahan

NYU Press (hardcover, $35)

On Rikers, a small island in New York’s East River, thousands of people live in captivity, held hostage in the city’s largest jail. Since 1932 people have been shuffled onto and off of the island on a daily basis, unendingly, either being detained while awaiting trial or, less frequently, serving sentences deemed too short to merit being sent to upstate prisons. Those serving their sentences on the island do what is colloquially known as “city time.”

The authors of the new book City Time: On Being Sentenced to Rikers Island offer an eye-opening look inside life at Rikers and the various trials and tribulations experienced by those serving city time. The book is not a history of Rikers Island, nor is it a prison memoir of life inside. Nor is this the first time that the two coauthors, David Campbell and Jarrod Shanahan, have written about Rikers. In 2022 Shanahan published Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage, a crucial look at the last 70 years at Rikers in relation to the rise of Black Power activism and mass incarceration. And in the 2023 collection Rikers: An Oral History, Campbell is one of 130 people who shared their deeply personal accounts of being held captive on the island. Unlike either of these previous works, however, City Time offers a comprehensive examination of daily life on Rikers Island as recounted by two men who served brief stints on the island for their political activism.

Full disclosure: Campbell and I corresponded while he was incarcerated at Rikers. While imprisoned he had an essay featured in the Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners calendar (of which I am a collective member); and, post-release, he was kind enough to share some of his experiences behind bars in a book I coedited, Rattling the Cages: Oral Histories of North American Political Prisoners.

With thirteen chapters covering everything from intake to release—including food, hygiene, interpersonal relationships, mental health, and substance abuse—City Time offers readers evocative firsthand accounts of the conditions of confinement for those held on the island, those working daily to “do their time” rather than let their time do them. Surviving Rikers demands careful navigation of the nuances, subtle gestures, particular terminology, de facto and de jure rules, and the routines of incarcerated people and guards alike.

Campbell and Shanahan provide behind-the-scenes snapshots of how these nuances and rituals work and how they are utilized by those serving city time to bring order and a sense of empowerment to their daily lives. City Time paints a vibrant picture of state repression and structural neglect, of violence and uncertainty, of navigating intra-gang relations, and of how acutely many incarcerated people lack for mental health services. Things that may sound trivial to those of us on the outside— taking someone’s seat at the cafeteria, an unintentional hand gesture or nod, changing the channel on the common room TV, not cleaning the shared phone after using it—can be invitations for conflict. And yet there remains a sense of hope, a shared vision of a light at the end of the tunnel, that enables those held on Rikers to find common ground. As the authors note, “after a couple months of city time, solidarity with other inmates, especially in the face of hostility from staff, is already an engrained response.”

While the authors’ own experiences inside the most renowned jail in the United States serve as the book’s backbone, the personal is buttressed by ample facts, statistics, commentary, and history sourced from a variety of ethnographers, sociologists, prison historians, fellow incarcerated people, and even former guards and employees of the jail. Combined, these personal observations and scholarship help to illustrate the structural racism, socioeconomic violence, and ingrained misogyny that are foundational to the carceral system as a whole.

It is worth noting that City Time was written by two scholars. Campbell and Shanahan took their politics from the classroom into the streets, and it is for this that they were convicted. Shanahan was charged with assaulting an officer during a march on the Brooklyn Bridge to protest the grand jury’s refusal to indict the officers involved in the police killing of Eric Garner. Campbell was arrested at an antifascist protest of an alt-right gala in Hell’s Kitchen. Faced with city time, Campbell and Shanahan approached it as academics, analyzing and interpreting their repressive surroundings, learning the social world of imprisonment, and ultimately producing a critical study of an oft-overlooked aspect of the carceral system.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

While the jail system is “a stopgap measure, and a particularly violent one at that, for larger social problems attendant to capitalism and its inherent racialized inequality,” the authors note that “jails tell us a great deal about the broader social context in which they operate.” As they point out, while volumes have been written on mass incarceration, very little has been published on the experiences of short-stay confinement. As the Prison Policy Initiative illustrates, there are nearly twice as many local jails as there are state and federal prisons in the United States, and, in 2022, “about 469,000 people entered prison gates, but people went to jail more than 7 million times.” With numbers like that, putting a jail like Rikers under the microscope—as City Time does—is vitally important.

The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with Campbell’s incarceration on Rikers, providing him with an up-close look at what happens when a widespread consensus emerges among the U.S. population demanding the mass release of people held in jails and prisons. Rikers was a global epicenter of COVID-19, and some 300 people doing city time on Rikers were released, “suddenly deemed able to freely walk the streets.” Campbell describes how the pandemic “uprooted whatever remained of the ordinary daily routines.” After three quarters of those in his dorm were released due to the pandemic, “the living environment of those left behind flipped from one of scarcity to one of abundance” as those released left behind their belongings.

The carceral system thrives on the dehumanization and repression of those unwillingly held, but City Time turns this notion on its head, centering the human beings who are forced to cohabitate on this small island in the middle of a river, surrounded by the New York City skyline and the possibilities that lay just out of reach. For organizers, prison abolitionists, family, and loved ones of those held captive on Rikers—and for those who may be facing time on the island for their actions, political or otherwise—this book is a must-read, providing insight and knowledge into how to survive one’s jail experience with dignity and determination.

Until the Close Rikers campaign is successful in shuttering this notorious jail once and for all, City Time serves as a how-to manual for maintaining one’s humanity in the face of the constant repression and mundanity of life on Rikers Island. Once Rikers ceases operations—along with the abolition of all other jails, prisons, and places of confinement—then City Time will stand as a testament to the often arbitrary and needlessly brutal ways that the criminal legal system has sought to control and suppress marginalized populations and those willing and able to fight back.

Image: Kyler Boone/Unsplash