In her 2003 presidential address to the Association of American Geographers, Susan Cutter proposed a “science of vulnerability.” Building on the multidisciplinary tradition of hazards research, she argues that vulnerability science requires spatial solutions, because “vulnerability manifests itself geographically in the form of hazardous places.”

Vulnerability, generally speaking, means the potential or risk for loss. Losses in population vary geographically and over time. Social vulnerability, a concept from environmental science, is the degree to which a system, subsystem, or system component is likely to experience harm due to exposure to a hazard, either a perturbation or a stress/stressor. Researchers in environmental science examine how communities are particularly vulnerable (or resilient) to external shocks such as natural disasters, assuming that vulnerability is a social condition and a measure of societal resistance or resilience to hazards.

Typically, though, researchers focus on the vulnerability of individuals or groups rather than the vulnerability of certain places to potential hazards. Thus, in this final discussion I wish to promote a science of punishment vulnerability, in which I consider intense formal social control as a hazard akin to industrial waste, toxins, floods, and natural disaster. In other words, I ask what makes people — and the places where they live — vulnerable to violent, harsh, or deadly crime control events, and how could vulnerability and resilience be measured, monitored, and assessed in the field of criminal justice policy?

Owing to the literature on the collateral consequences of mass incarceration, we could consider that mass incarceration is a stressor that reverberates beyond the individual people ensnared in the system to mothers, siblings, partners, children, and neighbors. Such a model would direct our attention away from behavioral explanations of rates of punishment and toward understanding the risk of criminal justice contact as the stressor. If we see incarceration as a hazard, we can better see how its own social structure and institutions produce conditions that are unsafe for people.

Viewing punishment as an environmental hazard requires a more articulated discussion of what community harms are associated with imprisonment: the erosion of already-low economic bases, loss of political power, fractured families, and exposure to harsh and violent prison conditions over time (whether as incarcerated people or visitors) are just some of the harms and hazards associated with criminal justice contact for communities. Punishment vulnerability fundamentally shifts blame for mass incarceration away from communities and toward a set of structural factors driven by state policies and practices. Such a measure also begins to recognize social needs, including where the provision of economic subsistence has been missing or inadequate. Thus, punishment vulnerability represents a rupture in the value commitment of social welfare in a democratic society. And just as we should identify communities that are particularly vulnerable to harm, we should identify communities with stories of resistance to this hazard.

Cutter and colleagues present a social vulnerability indicator with 44 different measures. In the following table I present 18 concepts that, when examined at the level of counties, cities, or neighborhoods, demonstrate the vulnerability of particular places to punishment.

| Concept | Description | Increases (+) or Decreases (-) Punishment Vulnerability |

| Poverty | Poverty, and especially deep poverty, limits a community’s ability to absorb losses and enhance resilience to punishment (Western 2018; Harris 2016). | Poverty status (+) |

| Poor health | Poor health, especially mental illness, substance use problems, and chronic pain, may increase exposure to police encounters and the likelihood of incarceration (Teplin 2000; Adams and Ferrandino 2008). | Poor health status (+) |

| Race/ethnicity | Discrimination, animus, exclusion, threat, and lagnuage barriers affect exposure to criminal justice contact and residential location in high-hazard areas (Burch 2014; Godd et al. 2014; Sampson 2012; Pager 2003; Kurwa 2016; Bell 2020). | Non-White (+)Non-Anglo (+) |

| Employment loss | The loss of employment following punishment exacerbates the number of unemployed workers in a community, contributing to slow recovery in the cycle of incarceration and community return (Western and Sirois 2019; Pettit 2012). | Employment loss (+) |

| Political power | Voter suppression, removal from participation in elections, and running for office could also greatly affect the ability to enhance resilience to punishment (Manza and Uggen 2006; Behrens, Uggen, and Manza 2003). | Disenfranchisement (+) |

| Family structure | Families with single-parent households often have limited resources for dependent care and thus may juggle work responsibilities and care for family members who may be exposed to criminal justice contact. It also affects the resilience to and recovery from incarceration (Geller, Garfinkel, and Western 2011; Lee et al. 2015; Wakefield, Lee, and Wildeman 2016). | Single-parent households (+) |

| Urbanicity | Residents of small/rural areas may be more vulnerable due to persistent poverty and joblessness following deindustrialization, or the conditions of local economy and distance to social infrastructure and health (Simes 2018b; Burton et al. 2013). | Small cities (+) Small/midsized counties (+) |

| Education | Education is linked to socioeconomic status, with higher educational attainment resulting in greater lifetime wealth and earnings, which may insulate communities from incarceration (Pettit and Western 2004). | Little schooling (+) |

| Job opportunities | Access to job opportunities in a community will enhance community resilience and provide opportunities for financial stability and social integration (Kalleberg 2011; Bartik 2001; Bloome et al. 2007). | Job density (-) |

| Housing | Access to safe, affordable housing and a stable address create conditions that support community development and reduce residential instability (Sylla et al. 2017; Wood 2014; Geller and Curtis 2011; Roman and Travis 2006). | Affordable housing (-) |

| Vacancy/abandonment | Desertification and abandonment leads to community fragmentation and diminished social cohesion, which in turn reduces resilience. High rates of vacancy reduce property values and make neighborhoods vulnerable to quality of life policing (Gomez 2016; Ackerman 1998). | Vacant housing (+)Rapid population loss (+) |

| Social services | Access to hardship, educational, and employment organizations could intervene in the use of formal social control (Murphy and Wallace 2010; Comfort 2016). | High-density social services (-) |

| Health care | Access to insurance coverage, emergency and preventative services, screenings, dental visits, mental health counseling and psychiatric care, substance use disorder treatment, and other health-care services can enhance resilience and intervene when punitive institutions may play a role in health-care delivery (Turney 2017b; Wildeman and Wang 2017; Rich et al. 2014). | High-density medical, mental health, and substance use treatment services; insurance coverage (-) |

| Stigma | Places become stigmatized due to a combination of factors relating to race, poverty, substance use, and concentration effects (Eason 2017; Sampson and Raudenbush 2004). | Stigma (+) |

| Police structure | Overpolicing, hot spots, and militarization of police raise the risk of surveillance and criminalization (Stuart 2016; Alexander 2010; Go 2020). | Greater officers per capita (+) |

| Court structure | The potential harsh and punitive practices of prosecutors and felony conviction patterns [and] the over-reliance on misdemeanor legal practices produce harsher punishment outcomes (Kohler-Hausmann 2018; Pfaff 2012). | Harsh or frequent charges and sentencing (+) |

| Community supervision structure | High rates of community supervision (e.g. parole, probation) increase the level of surveillance and could lead to incarceration for technical violations (Harding, Siegel, and Morenoff 2017; Phelps 2017). | Concentrated or high levels of community supervision (+) |

| Prison structure | A prison system with greater capacity for incarceration could expose more people to the risk of punishment (Schoenfeld 2018; Eason 2017). | Prison capacity (+) Prison political economy (+) |

Using a “hazards of place” model, wherein the hazard is criminalization and punishment, I suggest that punishment vulnerability is a multifaceted concept that helps to identify those characteristics and experiences of communities that enable them to respond to and resist mass incarceration. These correlates have been derived from a broad array of research, including my own, and call for a robust and replicable set of measures that estimate punishment vulnerability in a diverse set of communities. Applying a hazards of place framework takes an important step toward challenging traditional analyses of mass incarceration that too often fall into simplistic discussions of individual blameworthiness, and worse, pathologize people, families, and communities for their misfortune and life choices.

Punishment vulnerability fundamentally recenters the problem of incarceration on the systemic and iterative failures of an array of criminal justice policy choices that have led to these conditions. It brings direct attention to the complex and interconnected nature of various components of policy and social life that create this vulnerability. It necessitates a direct engagement between quantitative and qualitative scholars and takes seriously the nested scales of both place (neighborhoods, cities, regions) and punishment (police precincts, court districts, prison jurisdictions). Critical to understanding vulnerability is studying the impacts of these hazards; sociology has spent a great deal of time examining these impacts. This kind of research asks: How do people survive in response to state-sponsored suffering, and how might these hazards be mitigated or eliminated?

The goal of this type of analysis is both the empirical study of how things go together and a call to action for research and policy. Our disciplines and shared social interest in reducing and perhaps eliminating the penal system as it stands suffer deeply from data silos and data poverty. I do not mean data on poverty—but rather, a poverty in our measures, our ability to link data and projects together, and our ability to study incarceration at the community level (largely due to the restrictive data-sharing practices across penal institutions). Few police departments share information disaggregated to spatial markers like the block or longitude/latitude of stops and arrests (though many departments use such data in the practice of predictive policing). Even more challenging, accessing data from any other criminal justice institution (i.e., courts, prisons, jails, probation, parole) is a feat of building and stoking deep relationships and long-standing trust between researchers and institutions. Disciplinary differences have also fractured and siloed research projects, such that sociologists, for instance, are unable to collect the most relevant and up-to-date health data, while their public health colleagues would greatly benefit from the expertise and data of sociologists, geographers, and environmental scientists in their attempts to study community-level phenomena. A science of punishment vulnerability centers the goal on synthesizing research efforts and data collections and sharing strategies for data gathering and dissemination, all while maintaining the highest ethical standards regarding public data sharing.

Our social policy levers are too few, our measures and instruments too narrow, and the mindset too individualistic to create the systemic, community-affirming change we need in the American system of punishment and social welfare more broadly. Currently, removal and harsh conditions of confinement are the exclusive tools on offer to communities for transforming safety and justice. However, after decades — and really centuries — of calls for change, the moment is urgent. We must begin to envision and enact a kind of membership in society that does not harm communities, that values liberty and human connection and does not provide safety only to those who can afford to be segregated from violence in communities and immune to the excesses of state violence. Mass incarceration is morally, economically, and politically unsustainable.

The findings presented in my work are very much along these lines: I ask for a refocusing and reframing of not only the places we study, but the places in which we choose to intervene. We can no longer ignore the clear patterns by which the state interacts with a variety of places and their unique social, political, and economic conditions.

The effectiveness of criminal justice policy has long been measured by lower reported crime rates and incidences of recidivism. Yet this system is remarkably effective at stripping communities of their members and exposing entire places to the specter of punitive responses to social problems. This, too, must be measured.

Reflecting on Monica Bell’s impactful essay on safety, justice, and dreams, I wonder how we can ask communities to survive decades of state-sponsored redlining, divestment, restrictive covenants, and state-sanctioned segregation, accompanied and extended by 50 years of mass incarceration, all while being maligned and blamed for their “criminogenic” social conditions, stigmatized by ameliorative policies, and treated as a sociological monolith by the scholars whose findings inform policy. Literally hundreds of thousands of years have been lost to prison life, and this is in Massachusetts — the state with the country’s lowest incarceration rate. That is an incomprehensible amount of time in what could be described as the best-case scenario for the role of the prison in community life. To the extent that the relationship between state and subject can be described, this is beyond estrangement or neglect. Mass incarceration represents the state’s total rejection of whole communities.

Communities have suffered greatly as commentators and scholars continue to conceptualize the effects of mass incarceration as an individual-level vulnerability. Indicators such as punishment vulnerability and others I’ve studied begin to describe what a vibrant and healthy community looks like and how incarceration at the scale and concentration found in American neighborhoods harms the health and vibrancy of everyone living in those communities. The dose makes the poison, as they say, and American communities are being poisoned by current conceptions and practices of punishment.

Excerpted from Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment. Copyright © 2021 by Jessica T. Simes. Reprinted with permission from University of California Press.

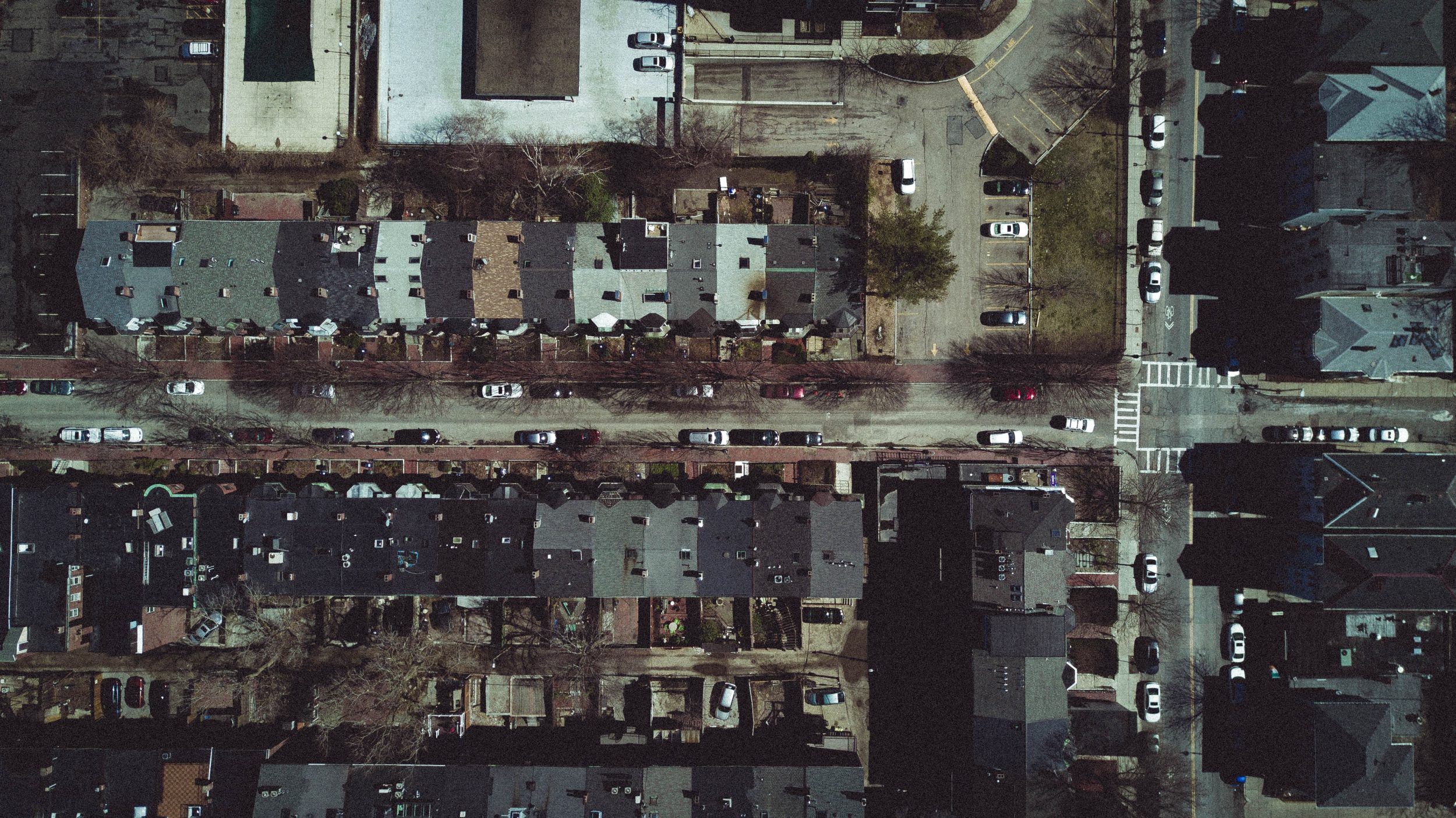

Image: Unsplash