Open date. These two words hold so much power for incarcerated people but evade thousands year after year. Finding those words on a parole decision means you are finally seen for the person you are and not defined by the nature of your original crime. They mean that for the first time since walking through the prison doors, they will open again soon. And this time, you will walk out of them.

But the reality is that these two words are rarely seen by the vast majority of people in prison. Long sentences and repeated parole denials continue to push the perennial finish line farther and farther away, under the guise of public safety. Some will die with the finish line in sight but never in reach.

Incarceration entails not just physical survival, but mental and emotional survival as well. As months turn into years and years turn into decades, your support systems age, too. Those visits, packages, phone calls, and letters become more infrequent. Death begins to consume the people you love the most, including those incarcerated with you. You adapt to crying without shedding a tear.

Agony, despair, and loss enter the hearts and minds of many. You begin to give up. The concrete and steel encase you, fear and doubt rise to the forefront; you begin to question whether you will ever get out of prison, or if anyone will miss you when you die.

I was released from prison in July of this year. When I got into the van that would lead me out of the prison, I was still told to sit in the back, the place reserved for people in custody of the state. Once we passed through the gates, I could then sit up front as a civilian. The crossing of that barbed wire line separating “property of the state” and “civilian” was not a reflection of any change in myself in the split second the van drove through the open gates. Instead, it was a reflection of the change in how the state’s correctional system viewed me.

I experienced the same at my first parole board hearing in September 2020. I was eligible for early consideration through what in New York state is known as Limited Credit Time Allowance, but was denied parole and told to come back in six months. In March 2021, I was granted parole. The only differentiating factor between September and March was how the parole board saw me. I had the same degrees, program completions, disciplinary record, and crime of conviction at both hearings. This has become even more obvious during COVID because all programming was halted and there was nothing else I could change even if I wanted to. But what did change in those six months was who happened to be sitting at the parole board hearing, deciding my fate.

My experience is not an anomaly. Thousands more are awaiting their turn at a shot at the golden ticket of an open date. And thousands more are losing hope as they realize the parole process resembles more of a scratch-off lottery card where it truly is the luck of the draw as to whether or not you will appear before commissioners who, at least in theory, will then adequately and holistically evaluate the person sitting before them.

As a result of the punitive nature of the prison system and an inconsistent, ambiguous parole process, older incarcerated people and those who have already served decades behind bars are dying at an accelerated rate.

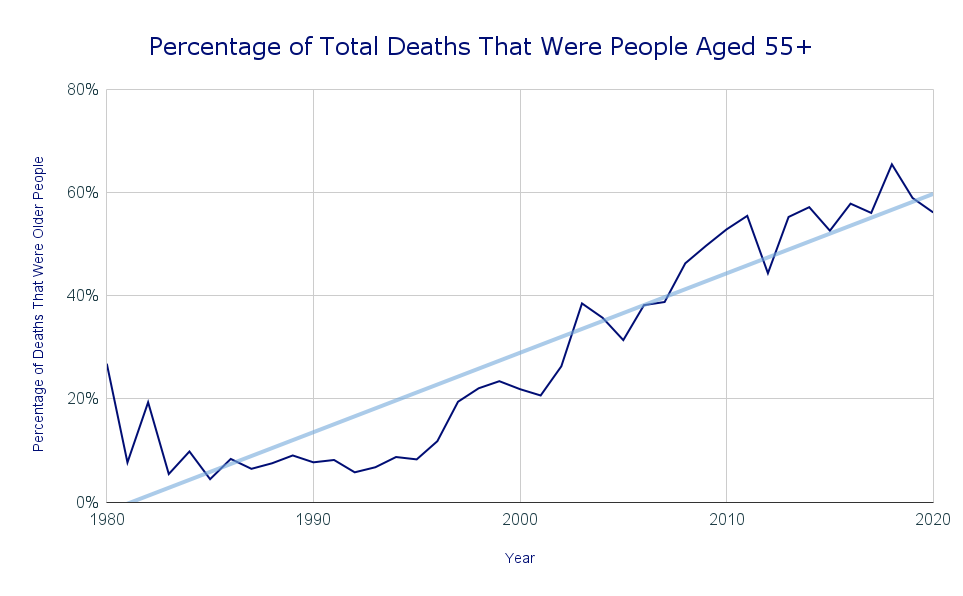

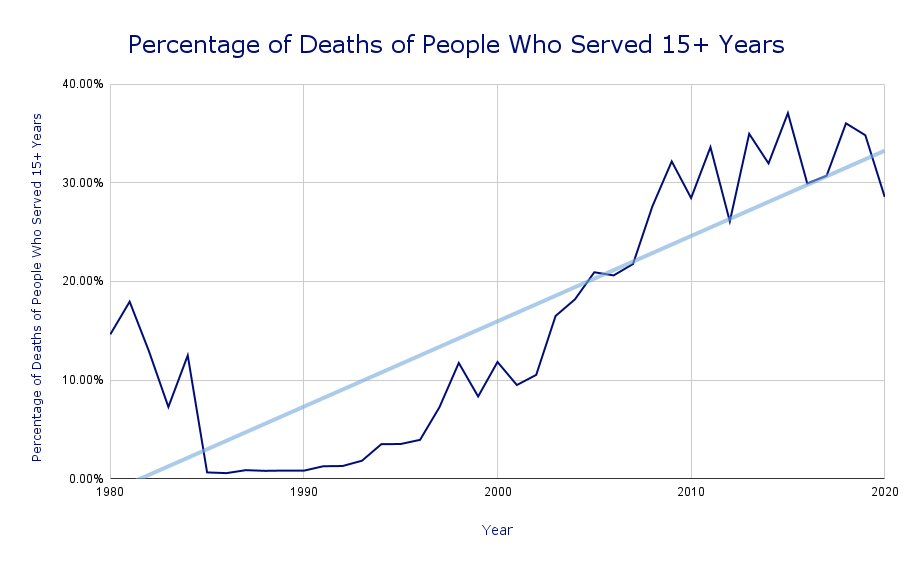

During the Attica Prison uprising 50 years ago, one of the many mantras was “strength in numbers.” Well, here are the numbers: According to a recent report by the Center for Justice at Columbia University, 1,278 people have died in New York state prisons in the last decade alone. Of those who died in the last decade, 56% were people 55 or older. Within this age group, the absolute number of deaths is skyrocketing: Between the 1980s and the 2010s, the number of deaths among incarcerated people in New York older than 55 increased 504%. At the same time, the people who are dying behind bars in the last decade have also been in prison for longer periods of time: One in three have already served at least 15 years. This is a drastic change from 1976, when one in 29 had been imprisoned that long.

Without policy intervention, it is safe to assume these numbers will remain high or, worse, continue to increase. The above graphs look almost exactly the same. But the first one represents deaths of people 55 and older, and the one after it represents deaths of people who had served at least 15 years at the time of death. They are rising concurrently.

Part of this precipitous rise can be attributed to the fact that prison ages people, and a lack of proper medical care exacerbates medical conditions in a way that would not happen if people were not incarcerated. It is not until the Department of Corrections decides that someone’s condition is dire enough that incarcerated people receive specialized treatment for their illnesses. This was especially problematic during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, as people became increasingly sick with no way to adequately protect or treat themselves.

Additionally, efforts to reverse the punitive consequences of our failed “tough on crime” eras have only impacted people serving sentences for so-called “nonviolent” crimes. Yet those who are aging behind bars serving longer sentences are mostly people who have been convicted of a violent offense, an arbitrary and muddy concept that may or may not include an actual act of violence. People convicted of such offenses are often the first to be left out of attempts to reduce the prison population. This explains why, as we have watched the total prison population decrease in recent decades, along with a decrease in the total number of deaths, the deaths of older people and those serving long sentences are growing at an alarming rate: the people dying are the people left behind by reforms that treat them — that treat us — as unworthy. We cannot meaningfully address mass incarceration without including these demographics of incarcerated people in our efforts.

In New York, the Elder Parole Bill and Fair and Timely Parole Act are policy interventions that can address this rise in deaths of older people and those serving long sentences. These laws would make an open date a reality for incarcerated New Yorkers losing hope.

The Elder Parole Bill will give an opportunity to people 55 and older who have already served 15 years to be evaluated by the state’s parole board on a case-by-case basis. Alongside the Elder Parole Bill, the Fair and Timely Parole Act will ensure that when people do get an opportunity to go before the parole board, that they are evaluated based on their current qualities — who they are at that moment in time — rather than solely on the original crime of conviction. It will also create a standard of parole that will require the parole board to make decisions through a more transparent and objective process, so a person’s fate is not so dependent on who happens to be sitting on their parole board hearing that day.

These bills will not only impact thousands of incarcerated people, but also their families. False hope and repeated parole denials put the families of incarcerated people on the same rollercoaster of emotions. Every time their loved one is denied parole, the very real nightmare of losing their family member in prison becomes a closer reality.

And for some of them, this has sadly come true.

A co-author of the Center for Justice report and friend of mine, Melissa Tanis, lost her father in prison in 2016. Towards the end of his life, despite being obviously ill in appearance, she and her father had no hope of release, as he had been denied parole and clemency and was not eligible to apply for compassionate release. It is a commonly held belief in prison that it is better to die anywhere else than behind bars. Prison robs families and incarcerated people of consistent connection with their loved ones, of a full life with their family members, and of the ability to be by their loved one’s side when they are ill or dying.

My open date was four months after I was granted parole. But for New York state the time is now to save lives and abolish New York’s new death penalty of perpetual punishment.

I have a young daughter who is pregnant with her third child. This is the first holiday season in 20 years that I will be able to spend with her and her family. I am grateful my daughter will have her father around for hopefully many more holidays. But I mourn with the families who will not spend this holiday season with their loved ones — either because they are still behind bars or they were one of the 7,504 people who have died in a New York State prison since 1976.

But just like there was strength in numbers in Attica, there is also strength in the number of New Yorkers who are appalled at the crisis of human rights violations in our state prisons — people who believe in second chances and who support parole justice. Our new governor, Kathy Hochul, has the opportunity to reunite families by granting clemency in time for the holidays and supporting parole justice.

My open date was four months after I was granted parole. But for New York state the time is now to save lives and abolish New York’s new death penalty of perpetual punishment.

Image: Unsplash