Avid MSNBC watchers and people in the legal academy may recognize Paul Butler from his on-air analyses and writings on the harms of the criminal legal system. But earlier this year, the former prosecutor-turned-academic also became a show host, helming Returning Citizens, a limited-run series on PBS. Before the pandemic, he and coproducers Brian and Virginia O’Reilly teamed up to cobble the documentary together piece by piece, one grant at a time. The six-episode series is one Butler describes as “subversive”—one with potential to move people who are not steeped in issues of criminal legal reform and advocacy.

In this conversation with Inquest senior editor Cristian Farias, Butler reflects on what drew him to this project, the challenges of bringing issues related to mass incarceration to a general audience, and what it was like to help people who have caused harm tell their stories. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cristian Farias: How did Returning Citizens come about and how is it different from other on-camera work that you’ve done?

Paul Butler: There are two interesting pieces to the show. One was PBS, where the audience was described as older and white. I’m a legal analyst on MSNBC, on cable news—and while the audience there definitely skews older, MSNBC has a really diverse audience. I wasn’t sure what the PBS audience would be like. I knew they were older. I knew that they were whiter. And I was interested in thinking about ways to reach that group—not so much about reentry issues, but just getting them to think about the criminal legal system in a more open-minded way.

The other interesting piece was my production partners. When I started working with Brian O’Reilly, one of the coproducers, he didn’t know anything about mass incarceration, about prisons, about reentry issues. This was in 2018—before the pandemic, before George Floyd but after Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, and Ferguson. The issue of reform of the criminal legal system was percolating in the atmosphere, but not as much as it became for a brief moment in 2020 after Floyd was murdered. We ended up having a really good working relationship. His wife Virginia is the coproducer, and I love them both. They’re an older white couple, again with no background on these issues. But one of the fun parts for me was watching their journey to, if not abolition, definitely abolition-adjacent, after meeting all of the amazing, wonderful people we met filming the six episodes.

Farias: Maybe this is a function of how the series is structured, but it’s not until episode three that people learn who you are—that you’re a former federal prosecutor who went through some experiences with the system. Obviously, you’re also well known from your scholarship and your work on MSNBC. But until then, PBS audiences don’t get to know that part of your background. I’m curious if burying who you are was intentional.

Butler: It was. I wanted to disappear, to the extent I could. When I was interviewing people, I wanted them to tell their stories. I’m not that well known. Most of the people I interviewed had no idea that I’m on MSNBC or that I’m a law professor. That wasn’t a big thing. And we certainly didn’t advertise to them that I was a former prosecutor, because I thought that might be a problem both in terms of getting people to talk to me, and in terms of the community. We didn’t want it to be like: Oh, finally, there’s something on PBS about returning citizens, and who’s hosting it? A fucking prosecutor. Give me a break. That wasn’t anything I wanted to lead with. I think it helped with marketing and with PBS, and it may have even helped with some of the grantors, but it wasn’t a way into the stories I wanted to help tell.

Farias: Why the focus on reentry?

Butler: When I think about the percolating issues in the criminal legal system, I think of mass incarceration and the police, and those are the areas that my academic work has focused on. But there are other issues like reentry. I don’t think Brian or his wife Virginia even knew that word, even though that was what the theme was. It was a neat opportunity for me to do a deeper dive. I met the folks whom we interviewed—either people who were coming home who or who’ve been inside—and after the third episode, I was all in. I was like, we have to get these stories on air.

Reentry carries less ideological baggage than things like police reform or mass incarceration. Reentry often resonates with faith communities because it’s about redemption and second chances. It should resonate even more than it does, but it does resonate with some members of that community. It even resonates with conservatives, with George W. Bush being an example of that, to the extent that it’s about responding to people who’ve served time, who’ve paid their dues. It’s a more palpable, less ideological way to enter into thinking creatively about the criminal legal system.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Farias: What are some challenges you faced in working with people not steeped in these issues?

Butler: There were two issues, both having to do with whiteness: the white savior complex and the white gaze. I didn’t want to present the show as though there were these people who were coming home from prison who needed help, and these white folks, out of the goodness of their hearts, stepped up. And there are definitely a lot of white people we talked to who, out of the goodness of their hearts, stepped up. But that’s not the whole story. And a lot of the story is what these women and men are doing and creating for themselves.

The other concern was the white gaze. Again, even though I understood who the audience was, I didn’t want to feel like I was explaining people of color to white people. I didn’t want to feel like I was explaining people who had caused harm, or people who had been locked up for dumb-ass drug crimes, to white people. I appreciated that that was the audience, but I wanted to be part of a project that would resonate with everybody.

Farias: I noticed that in the first few episodes, you start with the experts—with the NGO leaders and the lawyers who are trying to get people out—and then the formerly incarcerated people come second. But then as the show progresses, you flip that: the episodes start with the formerly incarcerated people who are trying to create their own businesses and find dignity in work. Then, toward the end, it’s just all formerly incarcerated people, such as Susan Burton and the women she’s helping. I’m curious if that was a conscious narrative arc.

Butler: I think it was, on the part of the producers. It’s not a documentary film, it’s a series, so there is an arc. The first episode that was shown on TV was the most visually appealing, with all the beautiful murals and a very diverse group of people. We talked to the woman who had given birth shackled, the good-looking blond artist who had also been locked up. I think that ended up as the first one because we wanted to kind of hook viewers. In terms of the response, that has been one of the most popular episodes.

I think the producers front-loaded the earlier episodes with experts and talking heads. But the more we filmed, the more we learned the obvious, which was that nobody could tell the story of returning citizens better than returning citizens. Not just on an experiential level in terms of what it’s like to be locked up, but in terms of expertise and best practices about reentry, rehabilitation, prison conditions, criminal law. There was almost nothing that we needed experts for that we couldn’t have gotten from the returning citizens themselves. That’s a lesson that we all learned, and I think your observation is exactly right. The more we filmed, the more we ceded space to those folks.

Farias: Naturally, you were gaining experience both as a host but also as an interviewer as the series went along. Did you have any big takeaways or a-ha moments about how to talk to folks about the harms of the criminal legal system and mass incarceration?

Butler: When you work with people who are coming home, one issue is: How much do you want to focus on what they got locked up for? I’m fine with asking the question because it’s relevant and it’s interesting, and I was a journalist in this context. It was part of the story. But when you mentioned the harms of the criminal legal system, that actually was an a-ha moment for me. This program isn’t so much about the harm that the returning citizens have caused, although most of them acknowledge that they have caused harm and that it’s important to make a contribution as a response to the harms they’ve caused. But the harm that the criminal legal system itself causes was also something they had expertise on. That ended up being more the subject of my conversations with them than what they had done.

The episode with the women was the next-to-last episode that we shot, and I don’t think I asked one of those women, other than Susan Burton, how they got locked up. It was all about their experience inside, their experience coming home, and their life before they went inside.

One of the things I love about the project is that I didn’t feel like there was a heavy editorial hand in terms of ideology or politics. We were just telling the stories, and the lessons were apparent. Kimberlé Crenshaw is one of my best friends, and she’s worked a lot on intersectionality issues and issues regarding women of color. I know from her work that a lot of women who get locked up have experienced violence themselves, and that there’s a relationship between that trauma and their being locked up. And I could write an academic article about that, maybe do a little finger wagging and say, “Well, hurt people hurt people.” But we didn’t have to do that, because the women just told their stories and it was clear. I always tell folks that I love teaching criminal procedure because I have my own ideas about what the Supreme Court and lawmakers are up to, but in practice, all I have to do is teach the cases. The students come to those conclusions on their own just from reading the cases and talking about them. I definitely have my own ideas about how our criminal legal system is working or not working, but I didn’t have to inject any of that ideology or politics into it. All I had to do was let these people talk about their lives.

Farias: In criminal legal advocacy or the criminal legal reform movement, there are these terms of art to refer to things that are very gritty and painful. In a way, “returning citizen” is one of those terms; we don’t want to say that they’re formerly incarcerated. Can you riff on that a bit in relation to the series?

Butler: That’s something that I thought about a lot. I asked a lot of the returning citizens we interviewed, both on and off camera, how they felt about the term. It’s a diverse community, and they gave a diverse set of responses. Some people were fine with it. Other people hated it. In terms of a description, it’s exclusionary, because a lot of people who are locked up are not actually citizens of the United States. And then “returning”—that implies that they left something, so what did they leave? There was a lot to unpack. But we had to name the show something, and that name was legible in the sense that a lot of people, even if they don’t agree with it, understand what it means. I don’t endorse it as the best term, but there is no single agreed-upon name for the community. It was also probably a little bit of marketing for the PBS audience—the word “citizens” being patriotic and inclusive of the audience, though it is not inclusive in other important ways.

Farias: Maybe that’s also related to your sense that this series is subversive. In order to be subversive, sometimes you have to use these phrases in order to convey a deeper meaning. In what other ways do you feel the show is subversive?

Butler: We talked to people who have been convicted of murder, of armed robbery. We talked to people who admitted that they committed crimes that they never got arrested for. A lot of those people were the nicest people you could meet. Even saying that now after meeting all those folks, it sounds weird to say. The cliché that we shouldn’t judge people by the worst thing that they’ve ever done—I think a lot of us understand that in an abstract moral sense. But if we’re thinking about murderers and rapists and armed robbers, I’m not sure that a lot of us take that to heart. I think after you watch the series, it resonates a lot more. If someone took the life of one of my loved ones, I don’t know if I would have the strength of character to be forgiving or nonjudgmental in that sense. But we talked to a lot of people who are forgiving, because many people not only caused harm, they’ve survived harm. We talked to people who are just strong, inspiring human beings. I think we subverted the idea of who a criminal is. Maybe it’s more of a verb, where crime is a thing that you do, but it’s not who you are. I hope that’s what comes across in the series. That’s a broad way of thinking about how it’s subversive: it confounds expectations, it upsets what you think, and I hope it opens your mind.

At this point, because of a lot of activism and scholarship, I think most people get the problems with the war on drugs. A lot of people understand, especially for people who have used, that it’s just dumb to incarcerate those folks. People don’t usually have that understanding about violent offenders. But a lot of what we now understand about people who have been locked up for drug crimes is also true about people who have been incarcerated for causing harm, including that treatment works better than punishment. One of the things I’m proud of is that a lot of the people we showcase in the series are people who have committed serious crimes.

Farias: You showed people who have caused harm and served lengthy sentences, but who then turn their lives around and are doing amazing things. I’m curious if the show also has another subversive effect—maybe not a positive one—where people will think that in order for us to do something about mass incarceration, people need to show their worth. They need to be deserving. They need to be model citizens. But a lot of the time, prisons did nothing to make them into who they are. If anything, prisons set them back. Even the parole process sets them back and causes a lot of harm. I’m curious if the show might make people think that prisons are good because they’re churning out amazing people.

Butler: I’ve worked with people who are coming home before in other contexts, and every now and then you run into somebody who says: Getting locked up is the best thing that ever happened to me. If I hadn’t gone to prison, I’d be dead right now. Obviously, you can’t discount someone’s own interpretation of their experience. My own idea is that it’s a failure of imagination to think prison is what’s required to make someone more productive. I can think of a couple of folks who I had that conversation with on camera, who’d say it wasn’t being incarcerated that turned them into the person that they are today. It might have been some of the people they met in prison—the other incarcerated people. But if they’re successful, it’s in spite of their incarceration.

It’s certainly possible that someone might watch this show and come away with the idea that prison was actually helpful, but I think if they listen to how the people who served time talk about their experiences, they’ll understand that it’s the strength of character, the humanity, and the survival skills that allowed them to survive on the street—even if not that successfully—that allowed them to survive in prison. And then part of it is that people grow up. The people who are at risk of being victims or perpetrators of violent offenses, like homicide and armed robbery, are mainly male and young. Part of what happens in prison is that they grow up.

Farias: I imagine there’ll be more stories to tell in the future.

Butler: I thought that we covered a lot in these six episodes, and I used to say that if we get a second season, we should move on to other issues. I still think that. But I can’t tell you how many emails, calls, and conversations I’ve had where people have said: If you do a second series, you’ve got to focus on this particular reentry issue, or talk about this amazing person who came home and is doing this amazing work. We could easily have a second series with six more reentry stories. I would prefer—and I think the producers at this point would also prefer—to broaden the lens to include other issues in the criminal legal system. We want to continue to tell those stories, but also to bring in policing, why we criminalize certain things, and ways of responding to harm that don’t involve punishment. I hope that we’ve primed the audience for those stories.

Farias: You even have a clip in one episode where you participate in a restorative justice circle. That’s not something you often see portrayed in stories about the criminal legal system.

Butler: That was so moving—and, again, subversive. When you think or read about restorative justice, it sounds kumbaya, loosey-goosey—like, what does that have to do with me getting my purse snatched? But it’s tough work, as I think you could see even from that little snippet. And it works. It’s effective. So just being able to do another season would be great. This series is not an op-ed. I write op-eds, and this isn’t one. This is just telling stories.

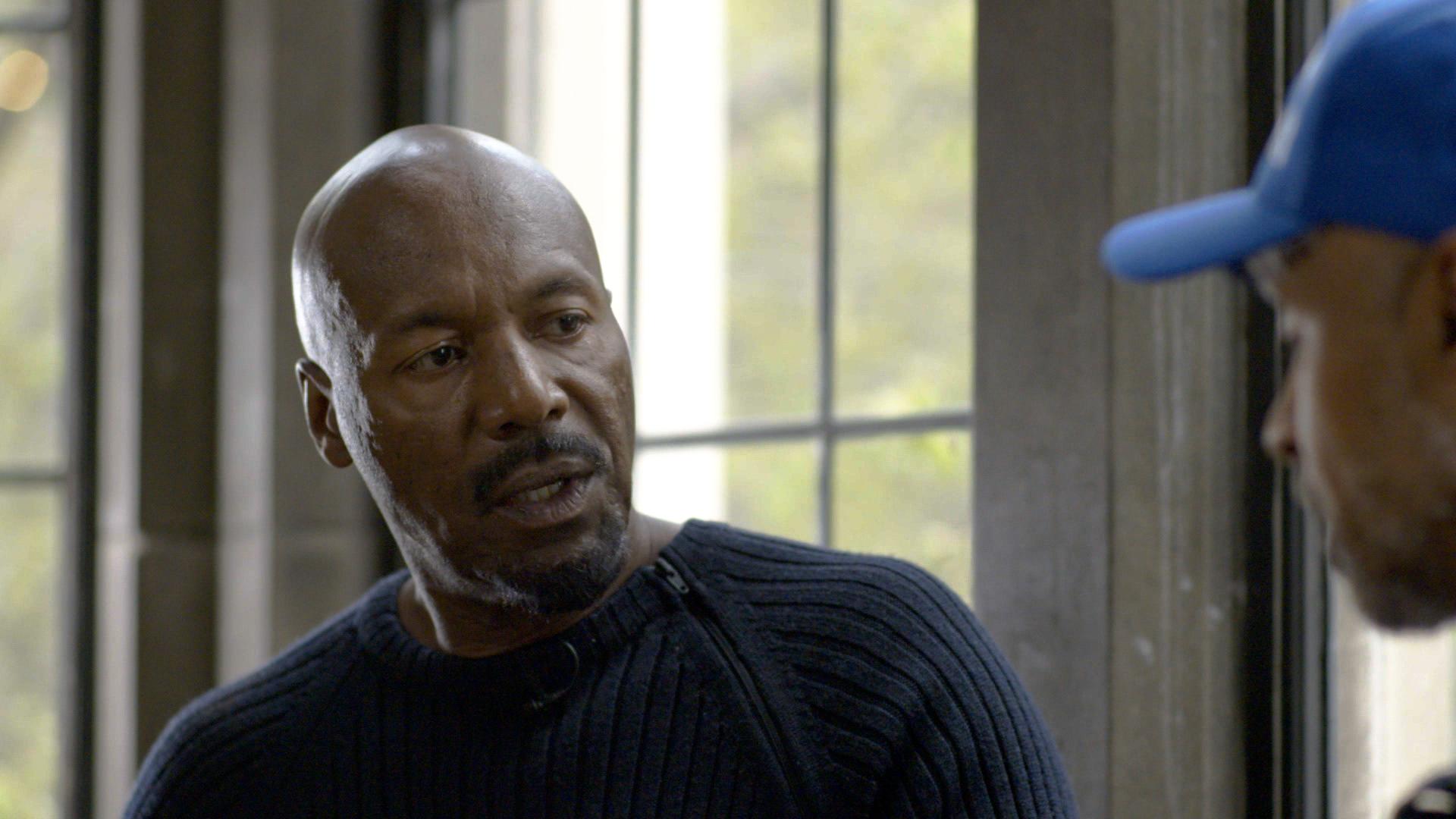

Header image: Purple Sage Productions