On a February morning in 2023, six police officers arrested thirty-two-year-old Detroit resident Porcha Woodruff at her doorstep. Woodruff, a Black mother who was eight months pregnant at the time, was detained for eleven hours and interrogated about an armed robbery and carjacking she knew nothing about. The reason? Gas station footage of the incident, fed into an AI-powered facial recognition algorithm, had identified her as the culprit.

One month and a $100,000 personal bond payment later, prosecutors dismissed the charges, according to reporting by journalist Kashmir Hill. For Woodruff, the trauma and humiliation of the experience remained. She had been arrested in front of her two young daughters and several neighbors and suffered contractions and psychological turmoil while in the holding cell.

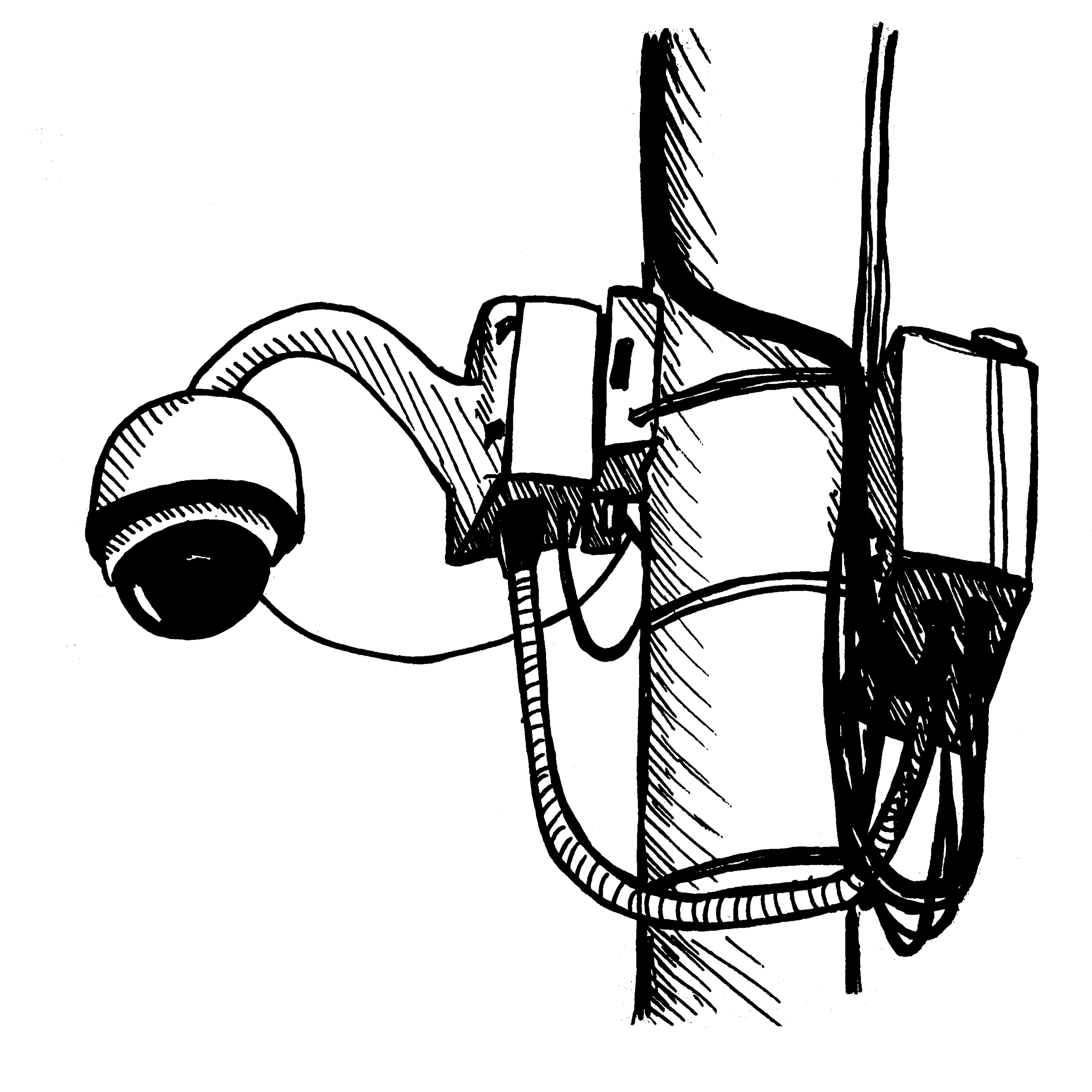

With the meteoric rise of AI, the U.S. criminal legal system has embraced the technology’s promise to streamline or automate traditionally human tasks under the logic of penal reform. But AI has worsened the system’s injustices. As previously reported in this magazine, the increased proliferation of facial recognition on video surveillance has made even more dystopian the longstanding problem of faulty witness identifications culminating in arrests, conviction, and execution. And it is not only potential criminal suspects who are in danger; today, products made by companies such as Clearview AI and DataWorks Plus—the latter of which was implicated in Woodruff’s arrest—are also being used to identify and surveil immigrants, protesters, and activists alike.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest—finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence & cited in The Best American Essays 2025—brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Facial recognition technology is just the tip of the iceberg. AI gunshot detection systems such as ShotSpotter send police to predominantly poor neighborhoods—areas where sensors have been installed to detect gunfire—and frequently misidentify sounds such as fireworks and backfiring cars, increasing the risk of deadly encounters with the police. In the courtroom, probabilistic genotype profiling software analyzes scant, messy, or low-quality DNA evidence to estimate the likelihood that it matches a person of interest. AI is used in a wide range of other criminal legal applications. It supports everything from predictive policing, which purports to forecast where crimes may happen and who might be involved, to surveillance tools like automated license plate readers and social media monitoring, as well as managing aspects of prison operations.

These technologies belong to a broader category my colleagues and I refer to as carceral AI—algorithmic, data-driven systems designed to police, incarcerate, and control human beings. The technologies under this umbrella are often adopted under the assumption that human bias or institutional inefficiency can be reduced through “smart,” “evidence-based,” or “data-driven” decision-making, strategically presenting the supposed objectivity of algorithms as a solution to the crisis of mass incarceration. The unfortunate reality is that, all too often, AI systems expand our carceral systems, under the guise of scientific rigor and technological advancement.

In a report on carceral AI, I along with a group of sixteen other interdisciplinary researchers and activists dispel the myths and hype surrounding these technologies. We shed light on the harmful effects of carceral AI, discuss ways to mitigate its use and expansion, and start to imagine a future in which the technology might actually help. The information presented here builds on the research and activism of participants in Prediction and Punishment: Cross-Disciplinary Workshop on Carceral AI, which took place at the Center for Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh in 2024. Here are some takeaways about carceral AI that readers can incorporate into the activism, organizing, and scholarship that they are already doing to try to combat the carceral state.

Police officers, judges, and lawyers have recently made headlines for using generative AI systems such as ChatGPT to draft police reports, invent legal briefs, and even interpret legal statutes. But the use of algorithmic tools in the carceral system long precedes the latest wave of hype around chatbots, and the logic behind carceral AI is rooted in long histories of control and colonization familiar to any abolitionist. As scholar Simone Browne argues, surveillance technology itself can be traced back to the transatlantic slave trade. Anti-Black surveillance tactics were developed during this time, such as the eighteenth-century “lantern laws,” which required Black, mixed-race, and Indigenous people to carry candle lanterns after dark if not accompanied by a white person.

More broadly, data has long been collected to track, divide, and control populations. This tradition was often motivated by the goal of increasing the occurrence of “desirable” human traits while eliminating “undesirable” ones. Eugenics, first popularized in the late nineteenth century, continues to underpin penal policies, which are based on the belief that certain “risky” parts of the human population should be isolated from the rest of society.

Today’s sophisticated AI tools build on older technologies that have been embedded in the carceral system for decades. Recidivism risk assessment instruments, such as early actuarial tools used in the 1930s and more recent systems like the Public Safety Assessment and COMPAS, are used to estimate an individual’s likelihood of rearrest for future crime. Their so-called “evidence-based” predictions are often inaccurate, and their use can lead to devastating consequences. They can shape decisions about pretrial detention, sentencing, and parole. Prison population classification algorithms such as the Pennsylvania Additive Classification Tool (PACT) assign an incarcerated individual’s custody levels during incarceration, affecting everything from their daily living conditions, their proximity to home, and their ability to access programming. The list goes on.

In recent decades, however, the ability to store, combine, and query data at scale has revolutionized the surveillance industry. Following the expansion of surveillance and information sharing in the aftermath of 9/11, police agencies now routinely collect massive amounts of data—known as dragnet surveillance—proactively, without a clear plan for how it will be used or shared later on. They can now access mass video surveillance, license plate readers, social media activity, geolocations, purchase records, phone call metadata, and biometric scans—all of which can be shared across agencies. This has massively expanded the glut of information at the carceral system’s disposal.

To make matters worse, private companies are playing an increasingly central role in this story. They profit off collecting data and selling it to police, prisons, and immigration agencies, whether in the form of raw data, software tools and services, or in-house consultancies. They include specialized companies such as Motorola Solutions and Flock Safety, which supply automated license plate readers to cities and police departments; billion-dollar corporations like The GEO Group and CoreCivic, which provide electronic monitoring devices and “community corrections” services to law enforcement agencies; and tech giants like Palantir, Amazon, and Microsoft, the latter of which the NYPD hired in 2009 to build their Domain Awareness System, a mass surveillance system that watches over the everyday movements of New York City.

With the rise of privatization, carceral AI has made the inner workings of the criminal legal system even more opaque. Many of these technologies are proprietary, meaning they’re protected as trade secrets and not subject to public records laws. On top of that, the algorithms themselves are often complex and hard to understand, making it difficult to spot errors, uncover bias, or challenge how decisions are made.

In the late 2000s, the Los Angeles Police Department launched a pair of programs designed to mine massive amounts of data in order to help predict sources and locations of future crime. PredPol (“predictive policing”) and LASER (“Los Angeles Strategic Extraction and Restoration”) were sold as reform programs to increase police accountability and efficiency.

Despite their promises of penal reform, programs like PredPol and LASER ultimately increase the criminalization of vulnerable communities. An analysis by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition found that a fifth of the people that LASER labeled as “chronic offenders” had no prior police contact. In a city where Black people make up less than a tenth of the population, nearly half of the “chronic offenders” targeted were Black. Businesses, residences, and community gathering places across the city were essentially blacklisted as “crime generators.” Officers were sent into neighborhoods with vague profiles of whom to target. LAPD killed twenty-one people in 2016, the year these programs expanded citywide. Six of them occurred in LAPD’s so-called “LASER zones.” All the men and boys killed were Black or Latino, four were shot in the back, four were teenagers, and two were under the age of eighteen.

Community organizing successfully forced the LAPD to end its controversial PredPol and LASER programs in 2019 and 2020. But instead of being scrapped entirely, they were simply rebranded. Immediately after discontinuing them, the LAPD launched a vaguely described new initiative called “Data-Informed Community-Focused Policing,” which combines data-driven policing with “community policing.”

The following year, the company behind PredPol changed its name to Geolitica. Its key tools were ultimately bought by SoundThinking, which itself is a corporate rebrand of ShotSpotter, the AI gunshot detection system mentioned earlier.

It’s no secret that the reason AI is often racist and classist—to say nothing of the other biases it carries—is because its training data is. Recidivism risk assessment instruments, for example, are infamous for misclassifying Black defendants as more likely to be rearrested than white defendants. Data on arrests and convictions is tainted by the systemic racism present at every stage of the criminal legal pipeline, from policing patterns to sentencing decisions. Basing predictions on this flawed data creates feedback loops where histories of discrimination justify future discrimination. Thus, much of the conversation about carceral technologies has understandably fixated on making algorithms more “fair,” with efforts directed toward implementing fairness benchmarks to improve the accuracy of risk assessment tools, facial recognition technology, predictive policing algorithms, and so on.

My colleagues and I grant that efforts to reduce algorithmic bias—when said efforts actually work—can sometimes lessen harm. That said, fighting to make carceral AI “unbiased” misses the bigger picture and works directly against abolitionist aims, obscuring the biases that the criminal legal system is built on and relies upon to operate daily.

The very act of basing sentencing decisions on someone’s age, gender, and educational attainment puts the incarceration of “risky” individuals at the center of how we respond to crime—an idea many consider to be inherently unjust. Moreover, even if an algorithm can be made fair in a statistical sense, the way carceral AI tools are used is unpredictable and can worsen discrimination. For example, judges who used a risk assessment instrument to decide prison sentences in Virginia gave harsher sentences to young and Black defendants than to older and white defendants who received the same risk score.

More broadly, carceral AI systems are often expensive to develop, justifying increases to police and prison budgets. The Sentence Risk Assessment Tool in Pennsylvania was intended to divert more people to non-prison sentences but ultimately had no impact on sentencing, despite taking nearly ten years to develop and being funded by taxpayer dollars. These are resources that could instead be invested into alternatives that already have robust empirical support, such as funding reentry support programs or releasing elderly populations from prison.

Focusing the conversation on algorithmic fairness accepts that carceral AI should be used, that the goal is to make incarceration more efficient—a well-oiled machine that becomes increasingly effective at putting people behind bars. In this way, it inherently limits the scope of the questions we ask. Among the most important: Is carceral AI creating the future we want?

Perhaps the most sinister feature of carceral AI is that it extends policing, surveillance, and incarceration to non-carceral spaces like homes, schools, hospitals, borders, and refugee camps. Technologies developed and tested in military and policing contexts, such as aerial drones and mobile spyware, are routinely repurposed to surveil and control individuals on the move as part of the so-called “smart border,” turning refugee camps and borders into de facto prisons. ICE also increasingly uses facial recognition software like the Mobile Fortify and SmartLINK apps to track and identify individuals, raising a host of human rights concerns.

Notably, some of the carceral technology companies mentioned earlier—including Palantir, The GEO Group, and CoreCivic—have recently seen “extraordinary” revenues thanks to lucrative government contracts under the Trump administration. Last year the Department of Defense announced a $10 billion agreement with Palantir. The Department of Homeland Security has used Palantir’s technologies to identify neighborhoods to raid and to build out a “master database” for deportation, while relying on The GEO Group to expand its capacity to monitor up to about 10 million undocumented people. These contracts are expected to expand further. Trump’s massive 2025 tax bill allocated $170 billion in additional funding for ICE, including $45 billion just for the construction of immigration detention centers.

Other agencies—including medical, public benefits, child welfare, and education systems—often enter into data-sharing agreements with the carceral system, enabling new forms of cooperation with police. For example, from 2014 to 2019, Ramsey County, Minnesota, prepared to use predictive policing to identify “at-risk students before they turn to crime.” The county and the school district agreed to share data and “apply predictive analytics to that information” to assess children’s risk for future juvenile justice system contact. Though the proposed system had the same logic as risk assessment tools used in the adult carceral system—to predict an individual’s future involvement in the criminal legal system—the county framed it as a way to help at-risk children and families get support and prevent their own criminalization.

When parents and local organizations learned about the plan in 2018, they formed the Coalition to Stop the Cradle to Prison Algorithm to oppose the data-sharing agreement. They worried that the algorithm would lead to more surveillance and criminalization of Black, brown, and Indigenous youth. Facing public pressure, the county stopped the project in 2019.

In Pasco, Florida, a similar predictive policing program—built on data about grades, attendance, and abuse histories shared with the sheriff’s office—produced a secret list of children “destined to a life of crime.” School police officers were instructed to use this list to surveil students, some of whom were as young as kindergarteners. Thanks to organizing work by the People Against the Surveillance of Children and Overpolicing, it recently became the subject of multiple federal investigations. In 2024 the DOJ settled with the Pasco County School District after finding that the program discriminated against students with disabilities, especially those with mental health conditions.

Similar cases of technology-driven surveillance and criminalization—and resistance to it—abound in the medical, public benefits, and child welfare systems.

In September 2025, a U.S. district judge dismissed a lawsuit that Porcha Woodruff had filed against the Detroit police six months after her arrest. Justice remains elusive for Woodruff, nearly three years later. Because of the secrecy surrounding AI use in policing, it remains nearly impossible to know how many people have been falsely arrested as a result of its use. Meanwhile, numerous lawsuits filed by individuals accused based on AI-derived evidence are still making their way through the courts.

Carceral AI is not a futuristic threat—it is a present-day reality, a logical extension of a system built to surveil and punish marginalized communities. While often framed as reform or innovation, these technologies deepen existing inequalities, obscure accountability, and redirect public resources away from investments in community safety. Challenging carceral AI requires more than calls for fairness or transparency. The most effective strategy to contest new branches of carceral AI is to identify and block the conditions that justify its existence.

As AI becomes thoroughly incorporated into nearly every aspect of our daily lives, combatting the carceral state increasingly means combatting carceral technology. Understanding what carceral technologies are being used in your community—as well as what strategies of resistance have worked in the past—is becoming an invaluable part of the abolitionist toolkit.

As scholar Ruha Benjamin reminds us in Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, abolition is not simply about ending harmful systems but also about envisioning new ones. Alternative visions of technology that subvert the power asymmetries of the carceral system already abound. Community members are using AI and data analysis to identify police officers and ICE agents who conceal their identity, predict whether a judge will violate the Constitution, reveal patterns of the criminal legal system’s failures, and map the location of surveillance technologies. In a moment when we are all subjected to unprecedented levels of carceral surveillance, turning the algorithmic gaze back at the powerful oppressors is one of our best strategies for reclaiming power and accountability.

We should ask what we want our technology to be oriented toward: Can we build software that is biased toward justice? Toward resistance? Toward eliminating systemic harms? Asking better questions and increasing community ownership will lead to technology oriented to making us all safer.

This article is an abridged and updated version of Prediction and Punishment: Critical Report on Carceral AI, a report first written in 2024 by Dasha Pruss, Hannah Pullen-Blasnik, Nikko Stevens, Shakeer Rahman, Clara Belitz, Logan Stapleton, Mallika G. Dharmaraj, Mizue Aizeki, Petra Molnar, Annika Pinch, Nathan Ryan, Thallita Lima, David Gray Widder, Amiya Tiwari, Ly Xīnzhèn Zhǎngsūn, Jason S. Sexton, and Pablo Nunes. Our work builds on the labor of activist collectives that have resisted and built understanding of carceral technologies, including the Carceral Tech Resistance Network, Stop LAPD Spying, O Panóptico, Against Carceral Tech, Mijente, Our Data Bodies, as well as Ruha Benjamin’s scholarship on carceral technoscience.

Art: Dasha Pruss