The intentions of immigrant detention centers are distinct from those of prisons. An immigration detention center is defined as an administrative center used to process cases that determine if and when a person can join legal pathways to residency or citizenship, or if they are deported. A prison is a place of punishment. This distinction was established in 1892 with the Geary Act, an extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which forced Chinese laborers to carry internal resident permits. Failure to do so would result in detention and deportation. Tracking the congressional debates of this period, historian Kelly Lytle Hernández illuminates in City of Inmates how forcibly removing persons from the United States (which involved detaining and deporting) was defined as administrative in part so the rights and punishments associated with criminal prosecution would not apply. This 120-year-old definition was again confirmed in 2009 by ICE administrator Dora Schriro: “Immigration proceedings are civil proceedings and immigrant detention is not punishment.” Being in the United States without proper authorization is technically processed as a civil issue, not a criminal one.

Yet the political right’s clarion call describes newcomers as illegals. One could easily connect such illegality with punishment: It seems purposely to evoke criminality. This type of xenophobic discourse is reflected in, and strengthened by, the architecture of migrant immobilization, which exists on a seamless continuum with prison design. In fact, whether one is comparing schematics or reflecting on the actual experience of being locked inside, one would be hard-pressed to tell detention centers and prisons apart. This invites questions: Where, between physical infrastructure and subjective experience, does imprisonment happen? And to what extent do the formal and material properties or systems of detention design influence social outcomes and human experience?

From the Series

Carceral Geographies

Essays exploring how mass incarceration shapes, and is shaped by, our shared world and built spaces.

To answer these important questions, we must investigate and discuss the architecture of immigrant detention, which can have as much, even more, impact on the experience of immigration as immigration legislation itself. Buildings erected outlast administrations. Building contracts and building industries shape the form and experience of immigration enforcement for decades beyond the moment of their conception and realization. Once a building is erected, there is built-in momentum to maintain it as an investment. Money is locked and situated. The affective meaning of a building does social, cultural, and psychological work on the people who experience it and see it represented. And finally, once built, buildings themselves influence their future management. That is, the philosophical and architectural ideas implemented in one moment act as a force against human interpretation of the same space in another moment. There is feedback between material worlds and social practices that is influential, not deterministic. Detention centers carry an inertia into the collective future of how U.S. society welcomes its newcomers.

In what follows, I pursue questions of how architecture and design shape the experience of immigration detention. To do so, I draw on my own research about the immigration detention infrastructure of Texas, which has long been a place of experimentation and expertise when it comes to defining and hardening borders and immobilizing immigrants. I also explore how, increasingly, the profit motive of private prison corporations such as GEO Group has played an outsize role in shaping these systems, in Texas and beyond.

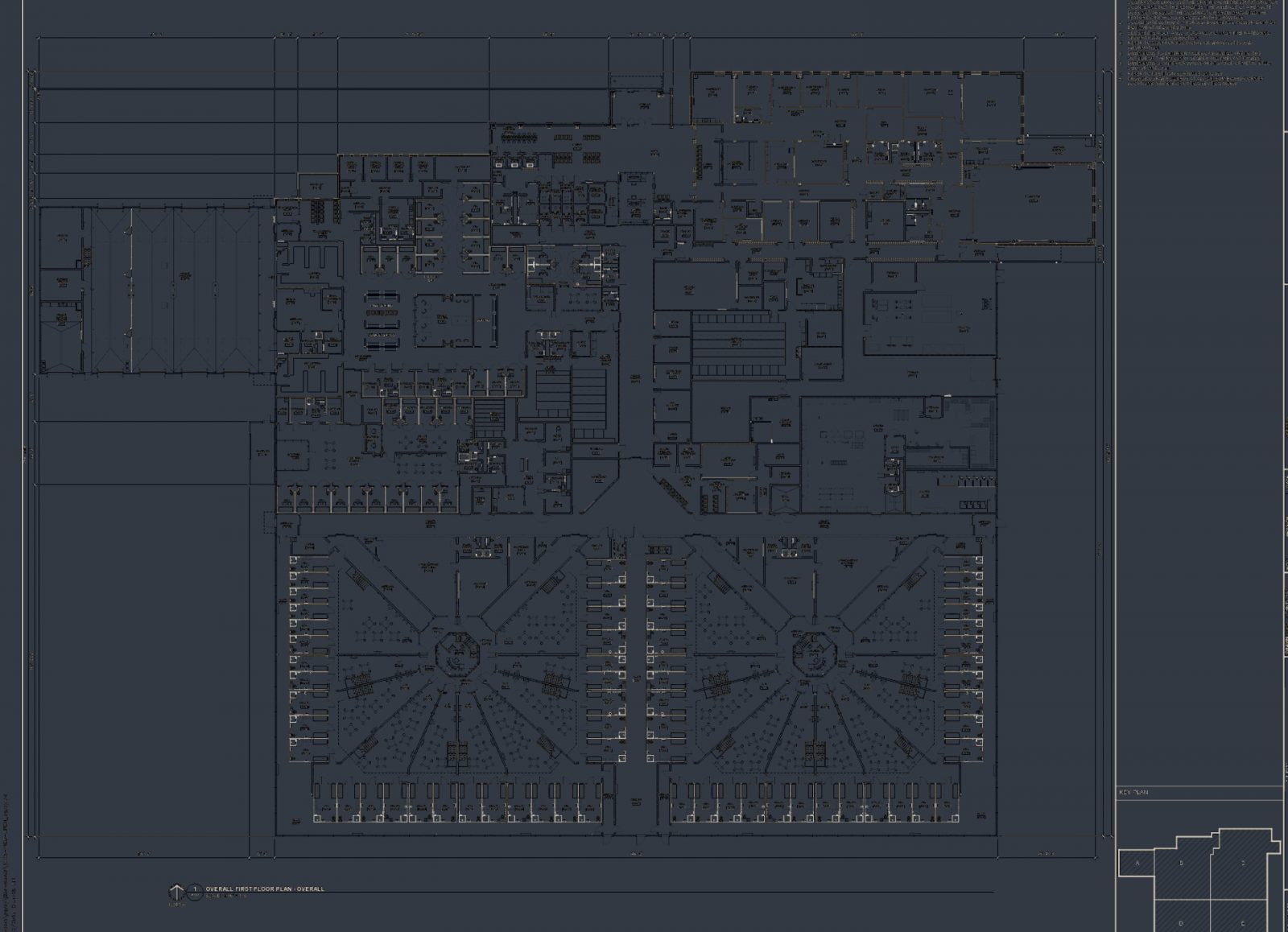

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, prison architecture stabilized around a few key layouts replicated in nearly every facility: the barracks, telephone pole, radial, self-enclosed, singular, and comb layouts. For the sake of this essay, these names are less important than the fact that aerial views and detention footprints of Texas’s immigrant detention landscape cohere with these archetypal prison layouts.

Take, for example, GEO Group’s South Texas ICE Processing Center (or South Texas Detention Complex) in Pearsall, Texas; more often it is just referred to as the Pearsall detention center. ICE published the Pearsall detention center plan in a manual used to illustrate government standards. Pearsall has a telephone pole layout, which means a central spine controls interior organization and circulation. The plan indicates that men, women, and juveniles are classified and categorized into separate wings (even though today the facility is all male). Along either side of the main circulation or “pole” are large dormitories. At the end of a phalanx of dormitories, three nodes comprised of individual cells are used for solitary confinement.

Many questions remain about who designed and built Texas’s immigration detention facilities during the 1990s and 2000s; ICE does not typically include information about architects or general contractors on government websites or in internal compliance reports. When this information is available, such as Argenta Architect’s design of Karnes County Civil Detention Center, firms have not responded to my inquiries. Nor have I been able to successfully secure architectural plans or building details from Freedom of Information Act requests. We know, though, that the 1990s–2000s was a period when U.S. carceral architecture in general was adopting increasingly punitive design elements. During this period, the Justice Facilities Review, the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) annual publication on “justice architecture,” sounded an alarm bell in relation to broader trends in carceral architecture. Juries composed of three architects and three practitioners from the judiciary, corrections, and law enforcement fields repeatedly described prisons as increasingly “non-normative environments.” By the end of the 1990s the jurors warned, “Feelings were that once a facility is toughened, there may be no going back—it is difficult to rescind philosophical and architectural decisions.” Twenty years later, not only have these ideas not been rescinded, but non-normative technologies of both design and management have expanded to create disorienting, dislocating spaces of maximum human deprivation.

The AIA jurors in particular identified a number of features that they felt marked the “hardening” of facilities: small dark cells, caged recreational spaces, an absence of natural light (replaced by “borrowed light,” where skylights and clerestories are used to channel indirect light in lieu of windows and fluorescent bulbs), heavy reliance on concrete floors, and crude signage. The jury identified the design of the “indirect supervision concept” where video surveillance and visitation, one-way glass, and nonoverlapping circulation spaces for both employees and detained immigrants meant that the incarcerated are watched but physically isolated. All of these features are evident in the three Texas immigrant detention facilities I have been able to personally visit (Don Hutto Family Detention Facility, La Salle County Regional Detention Center, and South Texas ICE Processing Center). They can also be seen in the dozens of photographs of other Texas detention facilities that are available on the Internet.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Private prison corporations have assumed the lead in designing “the hardening of facilities” in the name of efficiency. A top manager of JE Dunn Construction, which has built several prisons and detention centers in Texas, described the driving factor behind detention design as “cost per bed.” The private sector promised, and was able to deliver, faster construction (buildings were erected in two to three years rather than five to six), which translates to cheaper construction costs. Decisions about how to save money and build fast often happen in house. In 1992 GEO Group initiated a design/build component into their corporate structure that boasts green, efficient, standardized design practices. Prefabricated pods and building components are often constructed off site and then trucked into the remote sites of prisons and detention centers.

Private prison corporations make hard decisions so that ICE does not have to. In 2007 ICE published a Design Standards manual to “establish operational directions and architectural relationships for ICE spaces.” Plans, photographic illustrations, and dimensions describe ICE offices; details like window size and placement are articulated. But the ICE Design Standards from 2007 (I have not found a more recent version) are incomplete: they do not detail the parts of the building where migrants are to be housed.

In the section where the Design Standards purports to cover “Detainee Living Zone,” there are simply these words: “Contractor Operated.” This is on its face absurd: The design of the detainee living quarters exacts the greatest influence over the daily lives of noncitizens in ICE custody. Companies such as GEO Group that refer to this manual for detailed information about ICE’s “organizational” requirements find that it is their responsibility to fill in the gaps in the architectural plan that complete the real-life building. This lacuna at the heart of the architectural program severs the awesome power of the government to detain from the physical environment in which that power is exercised. ICE has made a crucial design decision: to abdicate its hand and role in design itself.

In addition to design, location plays a key role in how these facilities are experienced. Triangulating facility locations with nearby towns, cities, and immigration support services reveals a science of remoteness, whereby distance is maximized between different groups of people: migrants, loved ones, visitors, townspeople, judges, personnel, activists, doctors. Video visitation and even court hearings are ascendant. Security personnel is minimized through nonoverlapping circulation floor plans. Unlike an earlier generation of Texas facilities that were sited close to or in cities, today’s facilities are on average 105 miles from cities with pro bono legal services.

So far I have focused on infrastructure. But what actually happens when you introduce people into these spaces? Through my research, it became clear that the dislocation produced by the physical infrastructure itself—its design and remoteness—is exacerbated by an overlay of managerial cruelty: imposed tedium, enforced lack of privacy, and willful disregard for shared humanity.

Pearsall was built in 2005 near a town of about 9,000 people approximately 60 miles from San Antonio. GEO Group’s 238,000-square-foot facility can immobilize up to 1,904 people. To learn more about what the “detainee living quarters” were like, I asked formerly detained people to draw their pods.

Miguel, an asylum seeker fleeing Panama, was detained for four months and living at an immigrant shelter in Texas when we met. He drew a large rectilinear room with two long tables in the middle surrounded by bunkbeds. Toilets, sinks, and showers are depicted at one end surrounded by a half wall that ensured the men’s continuous surveillance (by both male and female guards). There was a small square room at the other end that had basketball hoops fastened to the wall.

Miguel explained that a hundred men (from all over the world) slept; ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner; went to the bathroom and showered; prayed and played basketball; or paced in this pod twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, with few breaks or exceptions. The pod has no skylight or windows. The outdoor space is a caged “rec room” with a narrow clerestory at the top that is covered with concertina wire.

The role that management played in the men’s sense of dislocation became clear when he explained a string of letters at the bottom of his diagram. Whenever Miguel would start to learn his podmates’ names and stories—in other words, as soon as they would begin to form bonds of friendship or camaraderie—the guards would call all the people by their bed numbers and reshuffle them into new pods. In four months, Miguel was reshuffled four times. The tension and fear would start all over again: Who am I sleeping next to? What will happen tonight?

This description aligns with another man I spoke with who was incarcerated in Pearsall for ten months. Muhammad Nazry Mustakim (Naz) was born in Singapore but brought to the United States as a child; he was a longtime green card holder. Before he was locked up in Pearsall, Naz lived in Waco, Texas, with his wife Hope. To see him for a one-hour “no-touch” visitation, she drove for eight hours round-trip across the state. Within the facility, Naz described his “detainee living zone” as a pod that contained 50 bunk beds and housed 100 men. Despite ICE’s mandate that “for at least one hour per day, detainees must have the opportunity for outdoor exercise or an indoor equivalent during inclement weather,” Naz’s “outdoor” recreation space was indoors. Naz told me: “You really don’t get to see the outside, you don’t get to see the grass or whatever” unless you crouched toward the ground to peer through a “very small drain hole for the water to flow out of the rec area. If you look through that you were able to see the grass on the other side.” Naz also experienced the systematic reshuffling as a challenge: “Each time I moved to a different dorm I always looked for a familiar face so I could feel comfortable in there.”

After Naz returned home, the soundscape of Pearsall stuck with him.

When I came home, I had real PTSD for like a week, coming back at nighttime. Whenever my wife would, like, try to wake me up, because I had nightmares of them trying to take me, to put me back in there. I was in trauma and covered in sweat and stuff. When I was in detention sometimes some officers would wake us up by banging on our beds, by kicking on our bunk beds making such a loud noise.

U.S. citizens pay taxes that finance places such as Pearsall. Most will never see these facilities, though. Even if they wanted to, gaining access is difficult. Detention is thus largely a black box occasionally punctured by investigations spearheaded by legal advocates and activist organizations such as the ACLU (“Justice-Free Zones,” “Warehoused and Forgotten”) and Detention Watch Network. From their accounts, as well as those of persons formerly detained, we know that detention (a federally sanctified and locally enacted arm of U.S. immigration policy) deprives humans of dignity.

Still, even when this veil is pierced, the result is often minimal. An uptick in public condemnation over the treatment of migrants in detention did not persuade President Biden to include immigrant detention in his 2021 executive order to phase out contracts between the BOP and private prison corporations. Skepticism, even cynicism, about the U.S. political landscape is an understandable response. Nonetheless, a radically different future is possible. One successful way to approach the dismantling of the detention landscape is as a hyper-localized fight over space. Activists working to shut down facilities have won major gains in California, Washington, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and Oregon, where efforts have led to the termination of Intergovernmental Service Agreements. Legislation to ban private prison corporations altogether has passed in California, Illinois, and Washington. Such state laws could create an awesome void. My hope is that in the future, rather than fighting the detention and deprivation of U.S. immigrants, we will be called upon to reimagine what welcoming newcomers looks like at our southern border and beyond.

Header image: A diagram of the Pearsall detention center drawn by Miguel, a Panamanian asylum seeker. (Source: University of Texas at Austin.)