Gideon v. Wainwright is widely regarded as a milestone in U.S. criminal justice. When it was decided in 1963, it was seen as a major step forward in assuring fairness to poor people and racial minorities. Yet, sixty years later, low-income and African American people are considerably worse off. Judged by the objective of avoiding prison or serving as little time as possible, a poor Black person charged with a crime in 1962 would have fared better than the same individual today. Gideon has not improved the situation of accused persons, and may even have worsened their plight.

In criminal cases, poor people lose most of the time. Not because indigent defense is inadequately funded, although it is. And not because defense attorneys for poor people are ineffective, although some are. Poor people lose, most of the time, because in U.S. criminal justice, poor people are losers. Prison is designed for them. Gideon obscures this reality, and in this sense stands in the way of the political mobilization that will be required to transform criminal justice. Gideon created the false consciousness that criminal justice would get better. It actually got worse. Even full enforcement of Gideon would not significantly improve the wretchedness of U.S. criminal justice.

This essay is from the series

Beyond Gideon

A collection of essays examining how—or whether—public defenders can meaningfully contribute to the end of mass incarceration.

For men hoping to avoid prison, being both poor and Black is a lethal combination. Black male high school dropouts are more likely to be imprisoned than employed.

What is it about being poor and African American that substantially increases the risk of incarceration? The answer, rather obviously, has much to do with class and race and, less obviously, little to do with the quality of the indigent defense system. The answer to the questions: Are poor defendants treated unfairly because many of them are Black, are Black defendants treated unfairly because many of them are poor, or is there some other dynamic at work? is Yes. Indeed, the Gideon decision itself was explicitly a class intervention but, implicitly, like other Warren Court criminal procedure cases, a racial justice intervention as well.

Approximately two decades after Gideon, two trends began in criminal justice, the effects of which were to overwhelm any benefits that Gideon provided to low-income accused persons. First, the United States experienced the most pronounced increase in incarceration in the history of the world. Second, there was a corresponding exponential increase in racial disparities in incarceration.

This dramatic expansion of incarceration was accomplished on the backs of poor people. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that the “generally accepted indigency rate” for state felony cases near the time when Gideon was decided was 43 percent. Today approximately 80 percent of people charged with crimes are poor.

The post-Gideon expansion of the prison population was also accomplished on the backs of Black people. There have always been racial disparities in U.S. criminal justice, but from the 1920s through the 1970s they were “only” about two-to-one. Now Black people are incarcerated at five times the rate of white people. As Michelle Alexander states, “If mass incarceration is considered as a system of social control—specifically, racial control—then the system is a fantastic success.”

Mass incarceration’s process of control—the social and legal apparatus by which poor people become losers in criminal justice—can be broken into five steps.

- The spaces that poor people live, especially poor African Americans, receive more law enforcement in the form of police stops and arrests.

- The criminal law deliberately ignores the social conditions that breed some forms of law-breaking. Deprivations associated with poverty are usually not “defenses” to criminal liability, although they may be factors considered in sentencing.

- African Americans, who are disproportionately poor, are the target of explicit and implicit bias by key actors in the criminal justice system, including police, prosecutors, and judges.

- Once any person is arrested, she becomes part of a crime control system in which guilt is presumed. Prosecutors, using the legal apparatus of expansive criminal liability, recidivist statutes, and mandatory minimums, coerce guilty pleas by threatening defendants with vastly disproportionate punishment if they go to trial.

- Repeat the cycle. A criminal caste is created. Seventy percent of freed prisoners are rearrested, and half return to prison, within five years of their release.

This description is not intended to be novel, or especially provocative. Other observers of U.S. criminal justice have made similar points about the process by which being poor and African American increases the risk of incarceration. Alexander notes:

It is simply taken for granted that, in cities like Baltimore and Chicago, the vast majority of young [B]lack men are currently under the control of the criminal justice system or branded criminals for life. This extraordinary circumstance—unheard of in the rest of the world—is treated here in America as a basic fact of life, as normal as separate water fountains were just a half century ago.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

But what if every person accused of a crime had an excellent lawyer? Proponents of Gideon suggest it would be an important step in making criminal justice more equitable.

In reality, though, full enforcement of Gideon would probably have little impact. If mass incarceration and racial disparities were caused by poor defense attorneys, it would make sense to think of Gideon as the appropriate solution. But, as the five-step process described above demonstrates, defenders are not the cause.

I want to be careful not to discount the difference that an excellent defense attorney can make, and how much this matters for individual clients. At the same time, I don’t want to overclaim that full enforcement of Gideon would bring anything remotely resembling equality to U.S. criminal justice. Nor would more effective defenders. The most favorable empirical evidence suggests that more able defenders reduce average sentences by 24 percent. For individual defendants, this reduction is very important. But even with a 24 percent reduction in every sentence, U.S. criminal justice would remain the harshest and most punitive in the world. The poor, and especially poor people of color, are its primary victims.

So then, what would make a meaningful difference for poor and Black people in the United States?

Perhaps counterintuitively, we need to focus less on abstracts rights and more on real need—a critique of rights I borrow from a school of legal jurisprudence known as critical legal theory. Nancy Leong puts her finger on the root of the problem when she notes that Gideon is “a milestone in protecting the rights of individual defendants” (emphasis added). It turns out, however, that protecting individual defendants’ rights is quite different from protecting defendants.

It is helpful to consider a concrete example. I was part of a team of lawyers that litigated a right-to-counsel case in Georgia. The attorney who agreed to take the case for the least amount of money was the attorney who was appointed, without regard to her competency to represent a defendant in a death penalty case. We made a claim that this did not satisfy the right guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment; the judge disagreed.

On one level the Gideon right is not abstract at all: a person cannot be sentenced to prison unless she is represented by someone who is a member of the bar (or she waives this right). The problem is that the right can be respected without accomplishing anything, as in the above-described cases. In order to make the formal right meaningful, it must be supplemented by some sort of standard-like provisions. But doing so introduces a high level of abstraction that does not decide actual cases.

The critique of rights means, in the words of The Bridge collective of legal scholars, that “rights cannot provide answers to real cases because they are cast at high levels of abstraction without clear application to particular problems.” In this light, the first recommendation of the National Right to Counsel Committee—that “states should adhere to their obligation to guarantee fair criminal and juvenile proceedings in compliance with constitutional requirements”—seems naïve. Most states would say they are already in compliance with the Constitution. Yet commissions and panels in Georgia, Virginia, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania have opined that these states are not in compliance with Gideon. Even the Department of Justice has acknowledged that “indigent defense in the United States today is in a chronic state of crisis.”

All of this sets up an extended, and furious, battle about what Gideon requires. The indigent defense community and the Supreme Court will agree sometimes, and disagree other times. Ultimately there are no “right” or “wrong” answers—an answer is “right” if it persuades a court. The vagaries of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the quality of lawyering that poor people are entitled to seem a risky foundation on which to position a social justice movement.

Mass incarceration and the vast race disparities that mar our criminal legal system will not be solved by individual rights. Imagine, if you will, that many people charged with crimes are legally guilty. Even if these defendants have excellent defense counsel, the prosecution still can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they did what they are charged with doing. Gideon encourages us to think of this as “fair.” The progressive investment in Gideon makes it seem as though the “poverty and crime” conversation is about the right to a lawyer in a criminal case, and not about the kind of conduct that gets defined as crime, the racialized exercise of police discretion, or why punishment is the state’s central intervention for African American men.

Gideon is a narrative about individual rights rather than a plea for class-based or race-based relief. This is consistent with Wendy Brown’s observation that “rights discourse . . . converts social problems into matters of individualized, dehistoricized injury and entitlement.” Gideon instructs us that we should respond to the problem that 80 percent of people charged with crimes in the United States are poor by trying to get a lawyer for a poor person charged with a crime. This will not solve the problem, and it changes the subject from mass incarceration and racial subordination to private entitlement.

In addition to its diversion function, Gideon also provides a legitimation of the status quo. Poor people—especially poor Black people—are incarcerated at exponentially greater levels now than when Gideon was decided. If more poor people are represented by lawyers because of Gideon, arguably their trials or plea bargains are fairer than before Gideon, when they did not have lawyers. Thus, poor people have simultaneously received a fairer process and more punishment. Gideon makes it more work—and thus more difficult—to make economic and racial critiques of criminal justice. This is not to say people cannot and do not make those claims, but rather that Gideon makes their arguments less persuasive. It creates a formal equality between rich and poor people because now they both have lawyers.

Gideon encourages the view that fairness for poor people is an issue of criminal procedure, not criminal law. When it establishes a procedural right, and poor people and racial minorities still complain, mass incarceration and racial disparities start to seem inevitable.

Critical race theorists posit that rights are unstable and incoherent—but still might be good for people of color. I agree: Gideon is profoundly limited and limiting, and yet a source of some good. For example, Gideon may save the lives of defendants in capital cases, who occasionally get better lawyers than they would in a world without Gideon.

Nonetheless, Gideon misidentifies the root problem. When the problem is lack of a right, one keeps going to court until a court declares the right. But when the problem is material deprivation suffered on the basis of race and class, where, exactly, does one go for the fix? Rights discourse does not necessarily lead to social change, and may impede social justice.

So what should people do? I am less certain about what methods will transform criminal justice than I am certain that Gideon will not. I do not view that uncertainty as a flaw: if people believe that holy water cures cancer, it is a contribution to demonstrate that it does not, even if one does not himself have an actual cure to offer.

Mark Tushnet notes that proceeding with an awareness of the critique of rights allows progressives “to improve the accuracy of the calculation of the possible benefit of investing in legal action rather than in something else—street demonstrations, public opinion campaigns, or whatever.” In the criminal justice context, the goal is to prevent poor people and African Americans from being losers in criminal justice, or at least from losing as badly as they do now. Advocates for the poor, for racial minorities, and for criminal defendants should abandon rights discourse and rather focus on reducing the number of poor people overall, and African Americans specifically, who are incarcerated.

Adapted with permission of the author and Yale Law Review from Paul Butler, “Poor People Lose: Gideon and the Critique of Rights,” Yale Law Review 122.8 (June 2013).

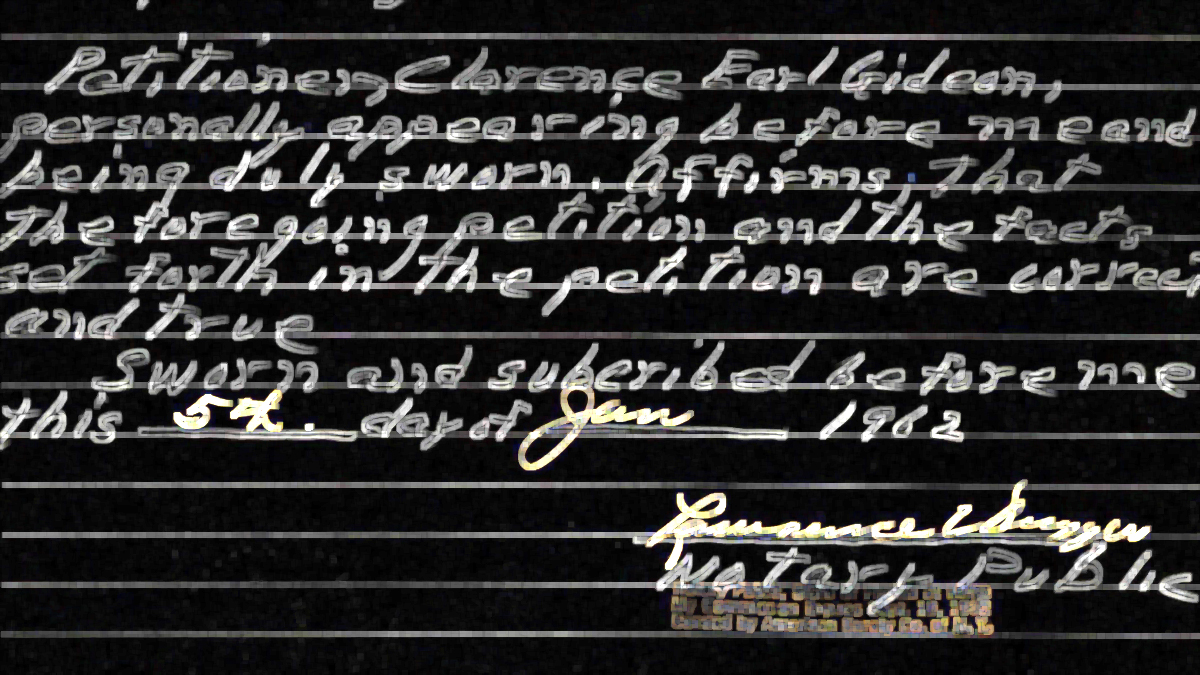

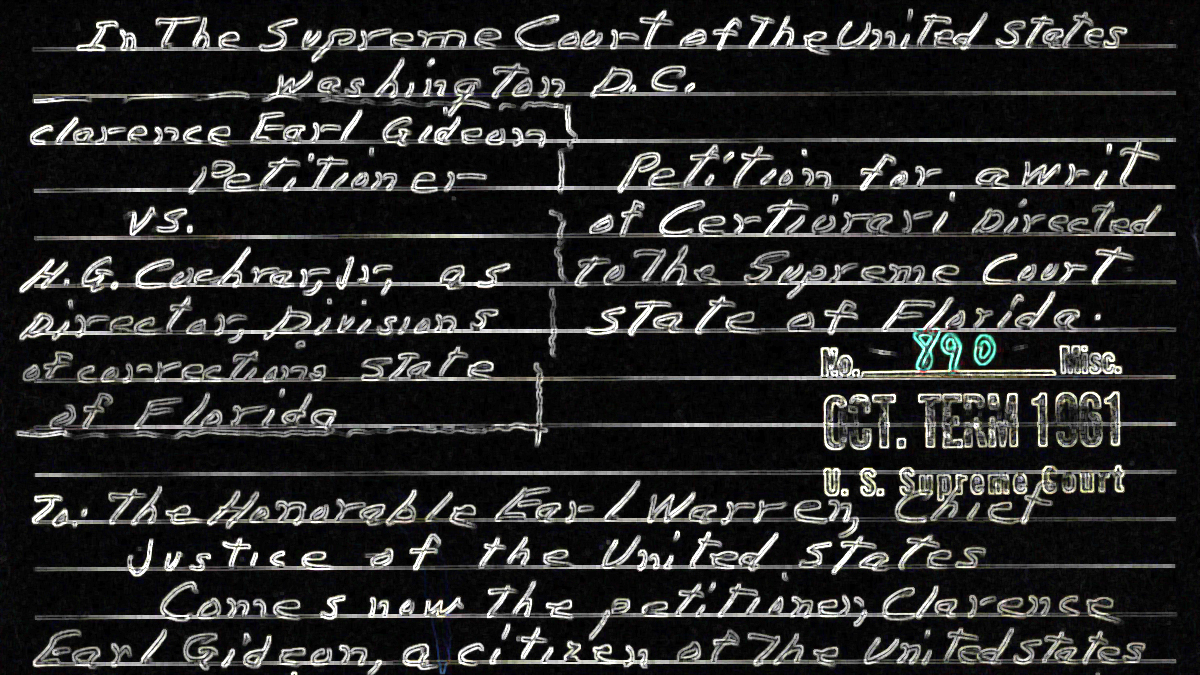

Image: National Archives/Inquest