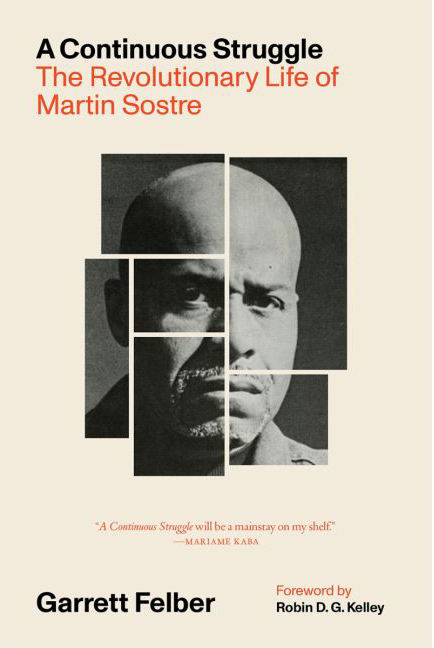

In A Continuous Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Martin Sostre, Garrett Felber vividly narrates the biography of Sostre, a revolutionary Black anarchist who spent decades of his life incarcerated in New York. After the Attica prison revolt in 1971, among the things carceral authorities found in the yard were Sostre’s legal decisions and published letters, which the incarcerated leaders of the uprising had been reading for inspiration. But in subsequent decades, Sostre has been largely forgotten. A Continuous Struggle seeks to reverse that trend. Last year, Felber previewed the book for Inquest’s readers, in an article that offers an engaging introduction to Sostre’s sweeping political vision (and which we suggest reading first). In the following interview, Orisanmi Burton (author of Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt) invites Felber to discuss Sostre and the tradition of Black radicalism he helped develop, and what they think today’s prison abolitionists can learn from Sostre.

Orisanmi Burton: Since this is Inquest, I wanted to start by asking you to talk about what Martin Sostre’s life can teach us about abolition. I know that this isn’t a major theme in the book, at least not overtly, but people are reading this book in a moment in which the concept of abolition is very much a powerful force in our political discourse. I’d love to hear you talk about how you understand Sostre’s political work relating to and/or departing from the frame of abolition.

Garrett Felber: I appreciate this question. There’s actually a certain tension in the two ways that I talk about Martin’s intellectual legacy—one of which is contemporary abolitionism and the other of which is Black anarchism—because neither of those are really terms that he used or embraced during his life.

He certainly played a role in developing those nascent ideologies, but he would have been more likely to call for abolishing the state than abolishing the prison. It’s useful, when we talk about prison–industrial complex abolition, to remind ourselves that it is a revolutionary ideology. It would require the overthrow of capitalism and other oppressive mechanisms. Even though I used the term “carceral state” in the subtitle of a previous book (Those Who Know Don’t Say), I’m very frustrated by the term’s redundancy. There is no state that is not carceral, historically.

I think it’s helpful to use the term “abolition” to translate some of Sostre’s ideas for a contemporary audience. But I think it’s also important to remind ourselves of the lineage of abolition as one rooted in the abolition of chattel slavery, which had both revolutionary and reformist tendencies, but was incomplete because it did not overthrow capitalism and the state.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

OB: Since you mentioned these two frames that you use, abolition and Black anarchism, could you tell me a bit about how working on this book expanded your conception of anarchism and Black anarchism, and what you learned about those politics and would want others to learn?

GF: I learned a lot about anarchism through writing this book. I came to the subject through a particular tradition of anarchism rooted in a central question: What does anarchism mean to Black liberation? That’s the tradition a lot of people who we would today describe as Black anarchists came out of: Kuwasi Balagoon, Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, Ashanti Alston, they’re all coming out of streams of Black radicalism that are revolutionary Black nationalist with aspects of Marxism–Leninism.

To me, it’s less important to describe Martin specifically as an “[adjective] anarchist”—however we want to fill in that blank. He used “revolutionary anarchist” to describe himself, but that was mostly so he could appeal to the young Black and brown folks he was trying to organize with. The word “revolutionary” had some valence to them that “anarchist” didn’t. Martin explained anarchism as a universal ideology that could be applied to the experiences of Black people in the United States. So I wanted to figure out—what were the particular aspects of that ideology that appealed to Martin under the conditions he was facing? In the book I draw out prefiguration and the propaganda of the deed, because I think those were the two that really appealed to him. And this idea of the relationship between individual freedom and collective liberation. Those were the things that he was wrestling with.

OB: You mentioned prefiguration, which you define in the introduction as “refashioning what is into what will be.” For Sostre, why was prefiguration so important to his politics? Could you share some of the moments we can see it at work in his practice?

GF: I’ll start by addressing your first question, about why he saw it as important. He put a real emphasis on what he called tangible counterstructures—physical spaces where people could see the manifestation of revolutionary ideas, where they could materially engage with those ideas and see them in practice. The three bookstores he started in Buffalo are an example of that; he described one of them, the Afro-Asian Bookshop, as similar to a community center and a library. They were places where people could sit and read, drop off their kids, use the phone, and just talk with Sostre about revolutionary ideas.

Sostre emphasized building on a small scale, setting up local structures that bring people into the struggle and sustain their involvement. These structures would then (he hoped) grow outward, connected to one another in a decentralized way with the goal of overthrowing the state.

Another aspect of his political activism that you could argue was prefigurative was his emphasis on print media. He had his defense committees buy a printing press and, at various points in his life, he edited revolutionary newsletters from prison. He saw his defense committee itself as prefigurative, understanding it as a revolutionary autonomous base that was fighting both for his release from prison as well as building political consciousness and community for deep, future-oriented struggle.

OB: I think prefiguration actually connects Sostre to abolition in a really direct way. Not necessarily to the concept as it’s popularly understood in the academy, but thinking about, for instance, what Ruth Wilson Gilmore says around abolition being a presence, where the prefigurative work of creating those durable structures is planting the seeds of the presence that then we have to grow and expand outward.

GF: I agree with that. Sostre would say, “If we do it right, it’ll end up right.” That’s the second piece of prefiguration, which isn’t just about building material counterstructures, but also about how we take care of each other, tend to ourselves, and tend to our movements and spaces so we don’t just wind up reproducing the oppressive structures that we’re trying to tear down. Our organizing has to be done in a nitty-gritty way that shows attention to the ways we socialize.

OB: This opens up to a larger set of concerns that I’ve often thought about, which is the way people debate the relative merits of anarchism versus socialism versus communism. I’ve always understood anarchism to be a necessary political dynamic within socialist and communist tendencies because it creates an internal critique of authoritarianism and different forms of violence within movements.

GF: It’s like Martin said in a letter to a supporter: “I believe that it is indispensable that we have such a network [of revolutionary bases] now not only in readiness to supplant this dying repressive State but to speed its demise. Otherwise, the repressive capitalist State will be replaced by an authoritarian State and we will have to go through the same shit all over again.”

OB: Throughout the book, you discuss Sostre’s belief in individual autonomy and the freedom of the individual from oppression—you name it in the introduction as his personal code of conscience. I’m wondering how you see that fitting into a more communal, people-centered politics of the masses. Do you find it to be in tension with the necessity for political organization, in which people are often asked to subordinate different aspects of their individual desires, or are we looking at a different scale of politics?

GF: I have another Martin quote for this. He said in an interview with Open Road magazine: “I don’t care what ideology you have, it isn’t good if it doesn’t afford a person-first personal freedom on its most basic personal, individual level. That is my concept of the struggle or the war of liberation. It’s not to replace one state by another, it’s to liberate the individual. I have not seen any state or government or society, whether it’s socialist or capitalist, where this freedom exists.”

His emphasis on individual freedom very clearly grew out of his experiences as, on one hand, someone who had those personal freedoms violated at the highest level during his incarceration. It makes sense to me that he would develop a theory of liberation that attends to individual freedom. And then on the other hand, his experiences within those very organizations that you’re talking about, where he witnessed the subordination of people’s individual freedoms to a party leader.

The example that comes to mind is his split from the Workers World Party (WWP). While incarcerated, he was producing a revolutionary Black newspaper, Black News. WWP members in his Buffalo defense committee were supporting the project with printing and distribution—not writing or editing, which Martin was doing himself. That was the intention, at least. But when members of the committee expressed hesitation about publishing his essay on political prisoner exchanges of captured U.S. diplomats for Black prisoners of war as a catalyst for urban guerilla warfare, that relationship deteriorated. His belief in the need for armed struggle conflicted with the WWP’s own theory of revolution. Ultimately, the WWP—likely with direction from Sam Marcy, the party’s head at the time—made the call not to run the article. When the news got back to Martin, he immediately broke with his committee and all the folks in the WWP. Black News was suspended after only two full issues and, a few years later, he started identifying with anarchism.

To this question, I would also say that people often assume the phrase “political organization” is synonymous with political organizations, and that we cannot be organized unless we are a part of organizations. Martin’s life demonstrates that there can be autonomous, decentralized organization—you can be politically organized without ever being really part of a political formation.

OB: I had the pleasure of being in conversation with you as you worked on the book, and I got to see how much of a struggle it was. A continuous struggle, if you will. One of the things we talked about was how, sometimes, Sostre was everywhere, and sometimes it felt like he was nowhere. He had such an outsize impact on the prison struggle in New York and yet it’s hard to find information or even any documentary evidence about his life. And so I wanted to get you to talk some about your methodological approach: How do you tell the story of a person who is so elusive?

GF: I think “absent presence” is a good way to describe these moments. There were trials where the judge would start whole discussions on Sostre—and Sostre was neither a plaintiff nor even in the court. After Attica, folks were talking about Sostre’s role in and relationship to the rebellion although he was at Wallkill Prison when it took place. Even the materials that were recovered from the yard at Attica after the rebellion included things like a copy of the opinion in Sostre v. Rockefeller and the pamphlet produced by his defense committee with his letters from prison.

I talk about it a little bit in the early chapters of the book when explaining the challenge of trying to piece together his early life. The prison plays such a disruptive role in destroying the records of people’s lives, both materially and also in their reluctance to talk about their experiences later in life. His son, Vinny, told me just how rare it was to hear his father ever talk about his early life or his years inside. It really became this challenging process of painting the picture of a world in which he was apart, even if I can’t say how he engaged with it, or just building out the little information I do have. Taking his mention of hearing Paul Robeson speak on the street and then giving the reader a sense of what that oratory tradition looked like, or knowing that he went to Lewis Michaux’s Black nationalist bookstore in Harlem and conveying the aspects of the bookshop which show up again and again and again throughout his life.

Really, the thing that I was struck by, which speaks to his political practice more than anything, is that I was able to interview so many people for the book. I didn’t know that I would be able to find so many people to talk to, and it was because he specifically organized with people who were so much younger than he was. Had he only organized with people who were within his age group, there would’ve been very few folks I could have found to talk to. But because when he was fifty, sixty, and seventy, he was organizing with people who were twenty, twenty-five, maybe thirty, there were people who were able to tell me about their relationships with Martin and share their own personal archives—letters, photographs, things like that. In a way, the archive reflects his politics. The absence of the archive reflects the repression of the state, and the presence of the archive reflects his organizing practice and the presence of his comrades.

OB: You made that point about him organizing with people of all different ages in the context of what that meant for you as a researcher, which I think is really interesting. Could you say more about Sostre’s intergenerational organizing? What does it say about his politics, and, even more importantly, what might organizers learn from that?

GF: Part of the impetus for writing this book was an intergenerational mission of sorts. I wanted to understand how people who were part of revolutionary movements of the 1960s and ’70s—many of whom were much, much younger than Martin—all knew his name, ideas, and actions, yet very few people of my generation know anything about him. I was writing with an imperative to make sure that his legacy of intergenerational organizing didn’t end with the folks who were active in the ’60s and ’70s. It’s such an important political practice to be part of intergenerational spaces, and not necessarily in a mentor–mentee framework, but more horizontally.

OB: Absolutely.

I know that you created an incarcerated reader’s edition of the book, which to my knowledge is the first such effort of its kind. What are the differences between the two versions of the book? How did you decide what changes needed to be made, and why was it important for you to make a specific version for this purpose? I’d also love to hear how it’s been thus far getting the book inside prison walls and what kinds of responses you’ve gotten from incarcerated readers.

GF: The differences are almost completely cosmetic. The title of the incarcerated reader’s edition just drops the word “revolutionary,” so it’s A Continuous Struggle: The Life of Martin Sostre. The copy on the back of the book about his life removes some words that might get flagged. These decisions were based on my own experiences with the superficiality of prison censorship. It’s also paperback instead of hardcover and has a slightly different picture.

Making this edition was important to me in large part because when I was writing the book, I was in conversations with and organizing with comrades on the inside. There is so much of incarcerated people’s knowledge, passed to me by these comrades, that ended up in this book—and really, so much of Martin’s life and legacy belongs to people inside and needs to circulate amongst those folks. Also, to put it bluntly, I spend a lot of my time getting other radical material into prisons, so absolutely I was going to do that for my own writing. It’s only been a few months, but so far, so good.

OB: As a point to end on, I think it’s worth highlighting that Sostre, fifty years ago, was talking about fascism encroaching beyond the prison walls and metastasizing throughout society, and now here we are in 2025, with people trying to resist fascism under the current administration. As people read this book at this political moment, what do you hope they take away from it?

GF: I wrote this book between 2020 and 2025, and one of the things I was mindful of during that time, and that I hope people will take away, is the role of incarcerated people in revolutionary struggles. I was also really struck by the dynamism of our social movements and the literally endless opportunities to become involved in them over the course of your life. That’s the continuous struggle: it’s not just about Martin as a single person waging this protracted war against the state, but also about all the other people who moved through his life, whose stories are told in this book, and how he shaped their political consciousness through struggle in ways that have radiated out into other forms of organizing.

Something like a defense committee, which could look on the face of it rather narrow because you’re fighting for this one person’s release from prison, is actually a variety of tactics and strategies of people from all different political ideologies coming in at different times in their own political journey. The defense committees were waging a struggle that was not merely about Martin coming home from prison. They played a role in all these other forms, from eco-defense in Potsdam to thinking about conditions of women’s jails.

And lastly, in writing this book, despite it being full of repression and terrible forms of torture, I always really felt Sostre’s revolutionary optimism. I hope people will take that from it too. The odds are against us, the power is against us, but that doesn’t make revolution impossible. And if you don’t believe it’s possible, you’re not going to win. Martin didn’t just say that, he really believed it—he always felt that we were right on the cusp of winning.

Image: Mike Hindle / Unsplash