In the summer of 2023, after a bad batch of meth made its way into his sweltering Texas prison, Jeremy Busby came close to being on the nightly news.

His prison had authorized a local television reporter to interview him about that summer’s slew of overdose deaths and other drug-related violence. But when the reporter showed up for the interview, she found the prison had transferred Busby, who has been incarcerated for over twenty-five years, across the state the night before.

According to Busby, the reporter was initially undeterred by this setback. She arranged to drive herself and her camera crew over 300 miles to interview him at his new facility. But then the prison blocked that interview, too. She did not try again.

In a relentless news cycle, canceled interviews often mean lost stories. And with them, lost opportunities for a public whose attention is increasingly fragmented to learn what is really happening inside the most secluded public institutions in the United States: our prisons, jails, and detention centers.

Cloaked in secrecy, insulated from press scrutiny, and cut off from the rest of society, these places often conceal violence, harm, and deadly oppression—all inflicted in the name of, and funded by, a public generally left unsuspecting and unaware.

By silencing Busby, his prison administrators joined a long line of actors who have cultivated public ignorance about what happens behind bars. In so doing, they help preserve the very conditions that allow mass incarceration to endure.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Busby’s story was broken by Theodore Amey and Seth Stern for Columbia Journalism Review last March. When we first encountered it, we were struck by its similarity to stories we hear frequently from Inquest’s incarcerated contributors.

Launched four years ago by the Institute to End Mass Incarceration (IEMI), this magazine was founded to create a space where “the people closest to the problem, including those directly impacted by mass incarceration, can come together to share ideas and be heard as they pursue bold solutions.” As our founding editors wrote when we first went live, Inquest exists to break down the walls of the silos that separate us from each other, “in hopes that we might all be better equipped to break down other walls together.”

No one understands those walls better than the intrepid journalists working inside of U.S. prisons to share their lived reality with the broader public. Of the hundreds of essays published at Inquest since 2021, roughly a quarter have been penned by incarcerated authors. Through these voices and IEMI’s related advocacy work, we have seen up close the barriers prison journalists regularly confront. And we’ve realized we need to take a more active role—not only in publishing these authors, but in working to advance and protect the rights of incarcerated and non-incarcerated prison journalists across the country.

As an institute rooted in the combined power of law and organizing, we are launching a new project aimed at identifying promising legal interventions that would improve conditions for prison journalism—with a broader goal of ushering a series of Prison Journalism Bills of Rights into law.

And as a magazine dedicated to helping those writers be heard, Inquest is pairing that advocacy work with this new series, Defending Prison Journalism, where incarcerated journalists across the nation, alongside experts and activists working to support them, will share essential insights into the challenges at hand and the path forward.

We spoke with over three dozen advocates and experts on prisons and press freedom, including over a dozen currently and formerly incarcerated prison journalists, about the challenges confronting prison journalism in the United States. Like others who have tackled this subject, we’ve discovered a web of state-made barriers to conducting even basic reporting on how U.S. prisons operate. Most of those barriers are rooted in policy decisions; all are enabled by law.

In a series of decisions stretching back to the 1970s—the decade that first saw the prison population explode—the Supreme Court sharply limited the First Amendment rights of people in prison. At the same time, the Court rejected the idea that “the media have a First Amendment right to government information regarding the conditions of jails and their inmates.” Taking these legal baselines together, journalists on the prison beat are working at a serious disadvantage. Even so, we found that the challenges they experience in their work extend much further than is often acknowledged or broadly understood.

Those challenges manifest in myriad and multifaceted ways, but across our many conversations a few themes kept recurring. First, prison journalism is often thwarted by both threatened and actual retaliation against journalists and their sources. Second, that retaliation is facilitated by relentless monitoring of attempted communication between incarcerated people and outside contacts, including non-incarcerated reporters. And finally, when retaliation doesn’t work, censorious officials often take steps to restrict, burden, or even altogether ban communication between the press and incarcerated people.

To be sure, some stories still make their way out, usually when courageous inside reporters risk prosecution or brutality to share what they know, including through channels of communication explicitly criminalized by the state. But for every story that breaks through, hundreds more wither inside.

Journalists behind bars, describing endless forms of payback, told us that retaliation was the greatest constraint on their work. Some, like Busby and others we spoke with, were subjected to “diesel therapy,” abruptly put on buses against their will and shuttled to new and unfamiliar institutions potentially hundreds of miles away. As our colleagues at Truthout have noted, California prison officials infamously threatened Inquest author and well-known prison journalist Ivan Kilgore with this “wildly disruptive” treatment when footage he recorded of COVID conditions inside his prison went viral.

Others found that their attempts to speak with reporters or document prison conditions drew harsh scrutiny from guards. Several reported retaliatory searches of their cells shortly after publishing a story, sometimes resulting in the loss of personal property. We also heard about trumped-up disciplinary actions and corresponding cuts to privileges like programming, visitation, and phone calls. For incarcerated people eager to remain connected to their loved ones, threats to these lifelines are often enough to stymie any desire to speak out.

Even more worrisome, many told us of retaliation in the form of unlawful violence. Some feared being labeled a snitch by guards, and the beatings or worse that might follow from other residents as a result. Solitary confinement, a mainstay of discretionary and torturous control within the prison system, was a regular fear—and too often a reality. Tariq MaQbool, a prison journalist in New Jersey, told us that in a particularly twisted act of retribution, he was sent to solitary confinement days after publishing a piece about solitary confinement. Another, Kory McClary, recounted being moved into the psychiatric unit and forced into an anti-suicide restraint as punishment for publishing an article about someone who suspiciously died in his New Jersey facility.

Outside journalists face retaliation, too. As Frank LoMonte and Jessica Terkovich report, when journalist Karen Olson refused to surrender notes she received from an incarcerated interviewee detailing abuse at a Florida jail, correction officials deemed the notes contraband—and pursued charges against her that carried a potential five-year sentence. A Florida appellate court upheld the charges, ruling that reporters like Olson were “simply not entitled to First Amendment protection” because the state has “virtually plenary authority to maintain order within its prisons,” and thus “may constitutionally forbid an unauthorized exchange of written communication between an inmate and an outsider.”

Rulings like these stem from the Supreme Court’s broader approach to prison law, which law professor Sharon Dolovich describes as “predictably pro-state, highly deferential to prison officials’ decisionmaking,” and largely insensitive to incarcerated people’s invocation of “such core constitutional rights as freedom of speech and expression.” And as advocates note, other impediments, such as the Prison Litigation Reform Act (enacted during the Clinton administration) and its state analogs, have effectively shut the courthouse door to incarcerated people hoping to find redress for such abuses.

To guard against retaliation, reporters on other beats will go to great lengths to protect the identity of sources who, to quote the New York Times’ anonymous source policy, risk “their freedom and even their lives by talking” about “the uses and abuses of power.”

But in prison, anonymity vanishes, replaced by the unblinking gaze of a panopticon: attempts to communicate with reporters or engage in reporting are subject to strict surveillance.

Consider here a sequel to Busby’s story that we learned while speaking with him. After his TV interview was thwarted, another journalist, Michelle Pitcher, later attempted to interview Busby for the Texas Observer, with slightly more success: she was able to meet with him in person. But at their first prison-approved interview, conducted inside of a non-contact visiting booth, they had an uninvited guest. A representative from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Communications Department unexpectedly followed Pitcher into the booth and sat down just inches behind her.

Looking back on it now, Busby shares an ironic laugh when he tells the story: “I said to Michelle, ‘She’s right behind you!’” When Pitcher asked the corrections official to move back, Busby recalls that the woman inched backwards, awkwardly wedging herself in the doorway while still craning her neck forward to listen. To our knowledge, Pitcher’s story is still forthcoming; Busby has only been allowed to meet with her twice.

Monitoring like this is an outgrowth of existing policies and laws. In Virginia, state policies instruct corrections staff to record in-person media interviews and keep the recordings on a person’s file indefinitely. Connecticut regulations demand the presence of a public relations representative at all media interviews with an incarcerated person, and authorize that official to end an interview at any time “based on the needs of the facility.”

Other modes of communication are even more closely watched. As San Quentin News associate editor Kevin Sawyer points out, incarcerated “journalists and other writers have no reasonable expectation of privacy,” which means that their telephone calls, emails, and written letters are routinely scanned by prison screeners, rendering them all “fair game to the ‘thought police.’”

In many jurisdictions, regulations expressly authorize prison officials to block whole swaths of media interviews from ever taking place. West Virginia, for example, permits wardens to deny any interviews that “may cause a disruption to facility harmony” or “contribute to increased levels of facility tension.” Tennessee only allows face-to-face media interviews with incarcerated people who’ve been handpicked by prison officials. Of twenty states we have examined to date, nineteen require prison official approval for in-person interviews, the sole exception being Vermont, which seems to allow such interviews under normal visitation rules.

Many states further refuse media access—by policy—for entire groups of incarcerated people, including those held in “special housing,” such as solitary confinement, where some of the worst abuses are hidden from view. Likewise, prison officials can cut off press access entirely during periods of emergency, frustrating press scrutiny when it is most needed. In 2013, for example, California prison officials cited such an emergency to bar press interviews and tours during a hunger strike protesting solitary confinement that was joined by 30,000 incarcerated people.

And when outside press are allowed to speak with incarcerated individuals, prisons may limit the amount of time or number of conversations that take place. In Arizona, for example, press are only allowed to visit one person during each trip to the facility. Other states impose short time limits on phone calls, followed by prolonged waiting periods between them.

Those who resort to old-fashioned mail encounter hurdles too. We learned of a Florida jail that limits all correspondence to and from incarcerated people to postcard-sized pieces of paper. Letter page limits forced John J. Lennon’s publicist to mail him proofs of his new book, The Tragedy of True Crime, spread across thirty-seven separate envelopes. And of course, mail is always screened, and frequently censored. Jeff McKee, a prison journalist in Washington state, told us that all mail mentioning violence between residents is simply thrown out by outbound screeners.

Violence, surveillance, burdens, bans. Capricious and unyielding, these tools stifle prison journalism. The results unfold as intended. Reporters go home. Stories grow stale. The public goes uninformed. And prison officials—often unmonitored, unaccountable, and unconstrained—are left to engage in any number of harmful actions behind their concrete veils.

And yet. In the face of these obstacles, people inside of prisons find creative and resilient ways to get their stories out—to the broader public and to people confined at other prisons. Since 1800, incarcerated writers at over 700 prison-sanctioned newspapers have reported on life in U.S. prisons.

Here at Inquest, we have featured films shot inside of prisons and collections of interviews that allow incarcerated folks to tell their stories in their own words—not to mention scores of essays penned inside of prison cells.

These stories are essential not only in their own right, but as necessary ingredients in the movement to end mass incarceration. As organizing teacher Marshall Ganz explains, stories are essential to movement work. They are how we connect not just to facts, figures, and arguments but to the people impacted by injustice and working to resist it—to survive it. Without these stories, the public is not only uninformed, but unmoved. And people within prisons are deprived of opportunities to connect across institutions, to learn from each other’s struggles, and to find power in their shared experience.

Prison journalism, in short, is essential for exposing—and ultimately undoing—the injustices baked into prisons themselves. That is why prisons try to suppress it. Today, there are just twenty-one prison newspapers in the country. And even these publish under the watchful eye of the warden.

As formerly incarcerated filmmaker Adamu Chan once told Inquest, this dynamic raises the fear that when prison officials approve or allow stories to come out, it is with their own carceral interests in mind. “What the Department of Corrections does,” he says, is find ways to bolster its own appearance in the media: “Look at what we’re doing now. Look at all these programs that we have for people inside now. We have a newspaper. We have this video program. We have these podcasts.” The fear, he concludes, is that this just “strengthens the system. It’s kind of a con game.”

Chan’s words were in our minds when we watched the opening sequence of The Alabama Solution, a documentary that premiered in October on HBO Max. The film makes extensive use of documentary footage recorded inside of prisons to expose egregious misconduct. Drug “treatment” wings where people are left to overdose on drugs smuggled in by guards. Feces- and blood-grimed cells overrun by vermin. And, most horrifyingly of all, beatings by guards who maim and kill.

As one New York Times review put it, “the pictures leave you practically speechless, and that’s the point.”

But to us, watching the film through the lens of this project, the film makes a subtler and more fundamental point. Across its 117 minutes, the only pictures shot within the prison on the familiar wide-format, high-definition movie cameras come from the opening sequence—when prison officials invited the documentarians in to film what the officials assumed would be a feel-good scene about a religious revival hosted in the prison yard. “Look at what we’re doing now,” Chan might say. When the camera crew started to walk instead toward the sweltering and overcrowded dormitories, trying to interview those inside, a guard’s hand quickly emerged to cover the lens. And the filming ends.

The power of The Alabama Solution lies in what happened next. For years, the outside journalists producing the film worked in close concert with inside reporters—including Melvin Ray and Kinetik Justice—to produce what the Los Angeles Times calls “one of the most shocking, visceral depictions of our carceral state ever put to film.” All shot on contraband cell phones.

Simply put, the journalism at the heart of this film was illegal to produce. Ray, Justice, and others involved had to risk prosecution—and not only risk, but experience, severe physical retaliation—to get their stories out.

And that, we think, is the point. As Ray points out in the film, “How can a journalist go into a war zone, but can’t go into a prison in the United States of America?”

Prison journalism should not be illegal. It should not be starved, stifled, or silenced. In a free society, attendant to the needs of all its people, including most especially those rendered wards of the state, our government institutions should be held accountable to the public—by a free press.

For that to happen, as this essay has shown, laws need to change. Specifically, reporters inside and outside of prisons need meaningful, material, legal protections—and the tools to enforce them—in service of searching and searing prison journalism.

Here at IEMI, that is the work ahead. In partnership with One for Justice, the impact team working alongside the release of The Alabama Solution, and the community of incarcerated authors and activists at Inquest, we are now at work drafting a model bill that we hope will inspire the enactment of Prison Journalism Bills of Rights across the country.

We are working to design this legislation to enshrine protections that non-incarcerated journalists and whistleblowers generally enjoy. We aim to codify broad rights of access to prison facilities, to ensure unmonitored and uncensored channels of communication, and to guarantee access to the essential tools and resources—including funding and compensation—that will help prison journalism thrive.

And, of course, we are working to build a statute that forcefully outlaws all forms of retaliation against prison journalists, and that creates the structures, frameworks, and incentives to ensure those protections are followed and enforced.

Legal reforms alone will not turn the tide of half a century and more of prison censorship. But they remain a necessary component of the broader sea change we seek, and are a contribution our team of lawyers, organizers, and advocates at IEMI is equipped to help offer. We look forward to sharing the model legislation here soon and to continuing its development with input from Inquest readers.

In the meantime, Inquest—through its weekly essays and, especially, its new Defending Prison Journalism series—will continue to make the fundamental case that a free country needs a truly free prison press.

Our goal in this work is to help break down the walls of secrecy that surround our prison system—for the sake of the people we incarcerate, and those we do not. For, in the words of Brandon Hasbrouck, prisons are laboratories of antidemocracy, where states practice tools of oppression that in time might be used against “the free population.”

As we write this essay, the Trump administration is wielding lawsuits, funding cuts, and regulatory threats to chill press freedom. At the same time, ICE agents have injured, arrested, and even deported journalists documenting immigration raids and border conditions.

In these times, the need to defend those who dare to expose state violence has never been more urgent. As incarcerated Inquest author Kwaneta Harris told us, “What happens behind these walls today becomes the template for how they’ll control everyone tomorrow.” The fight for prison journalism, in other words, is a fight for democracy itself.

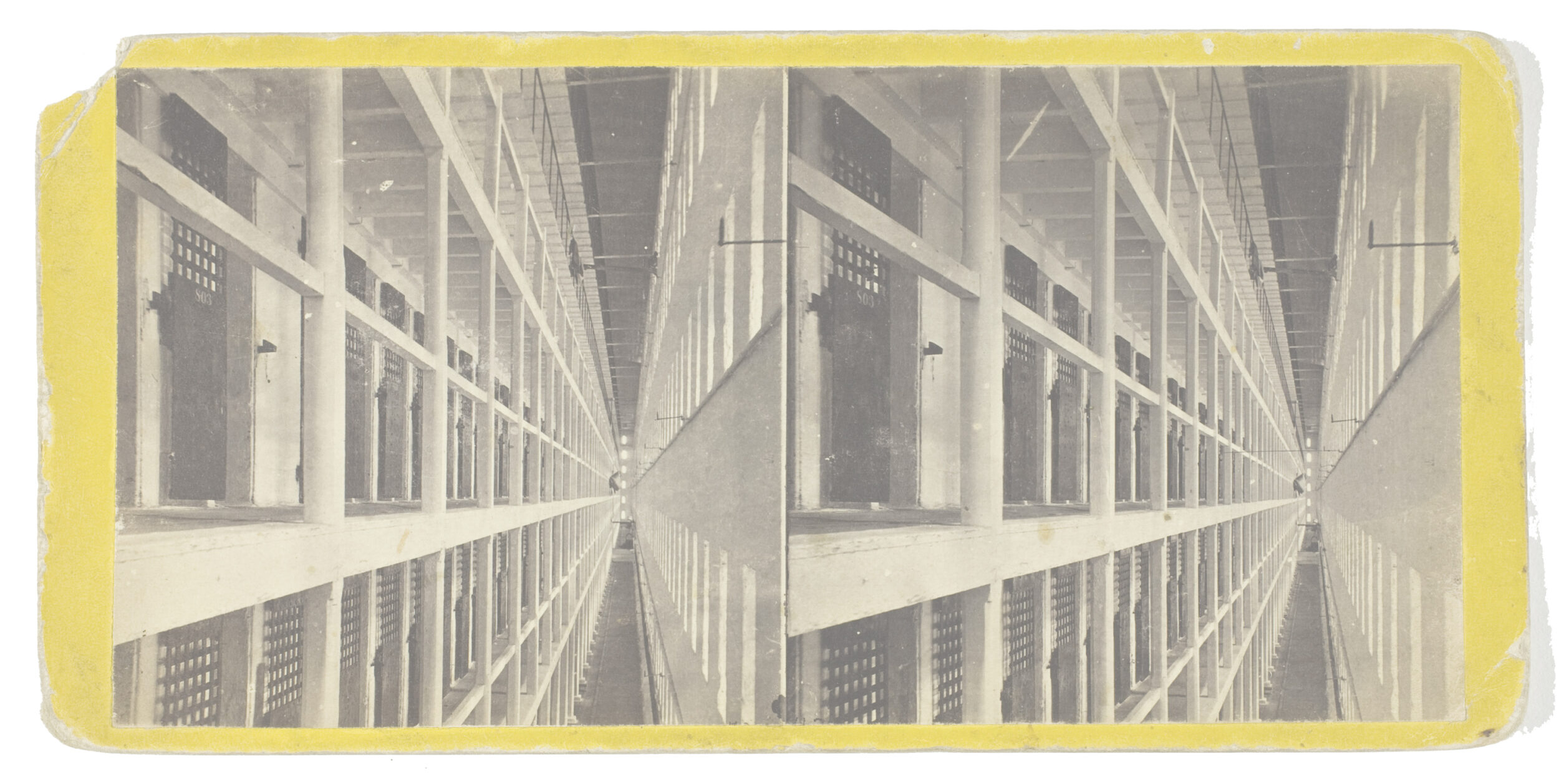

Image: “Interior view of the Main Hall of Prison, east side, which is 6 stories high, and contains 600 cells,” from Sing Sing Prison Views, a series of stereoscope slides printed c. 1860–69. In the collection of the Art Institute Chicago (public domain).