Letcher County is in the southeastern corner of Kentucky, where our state connects to Tennessee and Virginia. This temperate climate is home to over 150 tree species and lots of wildlife. It’s a beautiful area in Central Appalachia, in the oldest mountain range in North America. This area was formed about 350 million years ago by tectonic plate movement, and when the mountains buckled, a lot of the swampy grass got compressed as if in a pressure cooker; all that carbon became fixed as coal and natural gas.

Native Americans lived here for perhaps 12,000 years before they were displaced and killed by white European colonizers. Then, about 150 years ago, those same white pioneers became targets for industrialists and entrepreneurs, who realized Central Appalachia, including Letcher County, sat on all this mineral wealth. People who had lived on subsistence farms sold their mineral rights for practically nothing and many then moved into coal camps to work in the mines.

What was initially all deep mining over time began to morph into strip mining, where workers were replaced by heavy equipment. Strip mining is the devil incarnate, the bastard child of coal mining. The process removes the tops of mountains and shoves them into the valleys and streams below. It made some people super rich while permanently destroying much of the environment. Case in point: the devastating floods in Eastern Kentucky in late July 2022, which caused forty-five deaths across thirteen counties. The mortality was highest in areas that had been heavily strip mined because flooding was worse in areas with no watershed to hold the rain. And with the climate crisis, we had more precipitation overall. There were torrential rains and cloudbursts over narrow hollers but practically no watershed because strip mining had destroyed it. Many people were left without houses in what became a federal disaster area, visited by President Biden.

About two months after that flood happened, we got the news that the idea for a federal prison in Letcher County had been resurrected, after having been stopped in 2019. Activists did a lot of work to make that happen, and, in a twisted way, Donald Trump helped. He wanted to move the $500 million earmarked for the prison to his southern border wall instead, the one Mexico wouldn’t pay for. But in the context of the flood, these tone-deaf politicians didn’t seem to notice that we were in a crisis, struggling to pick ourselves up, yet they were willing to capitalize on the area’s tragedy and trauma, saying that it was about bringing jobs and money to the region.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Just like strip mining, this prison proposal has caused a schism in the community, the last thing anyone needed. On one side, there are some elected officials—and the locals they’ve managed to convince—who want the prison. On the other side are those of us saying: Wait a minute. This is not going to bring the economic growth you think. Just look at the other three federal prisons built in nearby counties over the last three decades. Those counties were not lifted out of economic distress, nor did a prison slow outmigration or the drop in school enrollment. Mostly due to the loss of coal jobs, Letcher County had a 14 percent reduction in population over twelve years, so of course people are concerned—but these other counties prove that a prison cannot fix us.

The Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) own data in its FCI–Letcher Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) says that groundbreaking wouldn’t start until 2026; then it would take thirty-six months to complete. That translates to no new jobs for two years, then only a “small” number of local hires for construction. After BOP transferees are brought in, in 2029, the BOP makes clear in the DEIS that the number of local hires will also be “small.” But people here need employment and we’re being told that this prison is the only viable solution. A prison, however, is the most devastating idea since strip mining. Prisons are places where dangerous things happen, both to those who are incarcerated and those who work there, and they tend to gut local communities where they’re built.

The coal industry’s exit from Letcher County left behind not only vast environmental devastation but an economic vacuum. It recalls the impact on central Kentucky’s tobacco farmers once the companies admitted that smoking causes lung cancer.

Central Appalachia, including southeastern Kentucky, is also one of the three areas of the country that was targeted by Purdue Pharma with OxyContin. We were absolutely blasted with opioids.

So, we’ve got an economic downturn with no end in sight, severe environmental damage, an opioid crisis that now has morphed into fentanyl and methamphetamine, then the COVID-19 pandemic, a deadly flood, and now a prison threat. And we were already stretched thin with limited mental health care.

Hold this in your mind and you can start to imagine how vulnerable our community is to predatory schemes like this prison, which is being fiercely promulgated by Kentucky’s Fifth District U.S. representative, and not contested by the Senate minority leader.

Our area is already struggling from fentanyl and methamphetamine overdose deaths, and now they would add a prison, where people are also prone to drug overdose deaths. These elected leaders are apparently unaware of The Marshall Project’s December 2022 report that there were 47 overdose deaths in federal prisons between 2019 and 2021, and while the BOP data doesn’t specify how many were from opiates, during that same period federal prison staff administered Narcan almost 600 times.

When an area has an adequate number of mental health professionals, the mental health of the community is better. Nationally, the average is 201 mental health professionals for a population of 100,000; Appalachia has 130. Letcher County is part of an eight-county area development district (ADD) served by a community mental health agency. Currently we have one psychiatrist—myself, now part time—and six psychiatric nurse practitioners, several of whom are also part time. These nurses are excellent, but that’s for eight counties. Our ADD also has a psychiatric hospital with three psychiatrists, but only one of them lives here; the other two live outside the area and provide care through telehealth.

If FCI–Letcher is built, it would add an at-risk incarcerated population of people who are not receiving adequate mental health care or substance use care to a geographic area that’s already suffering a mental health manpower shortage. This is almost completely ignored in the DEIS. In that BOP report, the “Community Services and Facilities” section contains less than a page about the region’s medical services, with no mention of mental health services. There are reams about engineering statistics, but except for a cursory mention about parameters of the First Step Act, there is nothing about mental health care or substance use treatment for these folks who are incarcerated. Why worsen the mental health suffering of both the incarcerated and those in the local community by ignoring these human needs?

Living in a small community can make it very painful to stand in opposition to a project like this, where people are being deluded that it will help them. Those of us who oppose the prison live with dual relationships among friends and family whom we love, but we become good at compartmentalizing: friendly at the post office or grocery, blunt at public meetings. In fact, when the BOP had its recent public hearing after release of the DEIS for FCI–Letcher, I thought for a couple weeks afterward that this opposition might be too divisive to our community, yet that is the raw edge of activism: when an issue is important enough that you take the risk of alienating loved ones. We are in an existential battle for the future of our community because this prison would transform Letcher County in ways that will prove irreversible.

Personally, at seventy years old and semiretired, it’s tempting to live up here in the beautiful holler and avoid any sort of conflict. There are moments when that is almost irresistible, especially after these public meetings. But if we can do something to help, we should do it. Alice Walker says that activism is the rent we pay for living on the planet. But it’s more than activism that is needed for Letcher County’s obstacles; we need to be smart, think big, and not settle. Most of all, we need to think about human beings and what the mental health environment is for those folks who are incarcerated. It is not acceptable, as human beings, to warehouse other humans just because, as the DEIS says, our community can get funding that way. If that’s the best that political and local leaders have to offer to get money into our community, then we are indeed in trouble.

These twenty years in time and resources spent trying to procure a federal prison in Letcher County would have been so much better directed toward something that could grow and expand our community. We could build a four-year college. We could put solar panels on every home so people could have some reduction in their power bills. Invest in infrastructure to give everyone high-speed Internet so that people could capitalize on the shift toward working from home and get jobs not normally available in the region. And getting water and waste treatment to rural areas should not be dependent on agreeing to a prison.

In an ironic way, it may be that Letcher Countians are already speaking out because there are currently ninety job openings among the three other federal prisons in southeastern Kentucky but only one Letcher County resident working in any of them. What does that say about the desirability of these jobs? Like the BOP says in its DEIS, either local people are not interested in those jobs or can’t pass hiring requirements. Either way, they’re not biting.

A major reason for our current economic distress is because of the blessing and curse of our natural resources, which misled us into putting all our eggs in the basket of a fossil fuel single economy. Now, however, we have an opportunity to evaluate all ideas and make better choices for our children’s future.

Editors’ Note: Inquest is published by the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, a member of the Building Community Not Prisons coalition that is working to stop the construction of FCI–Letcher.

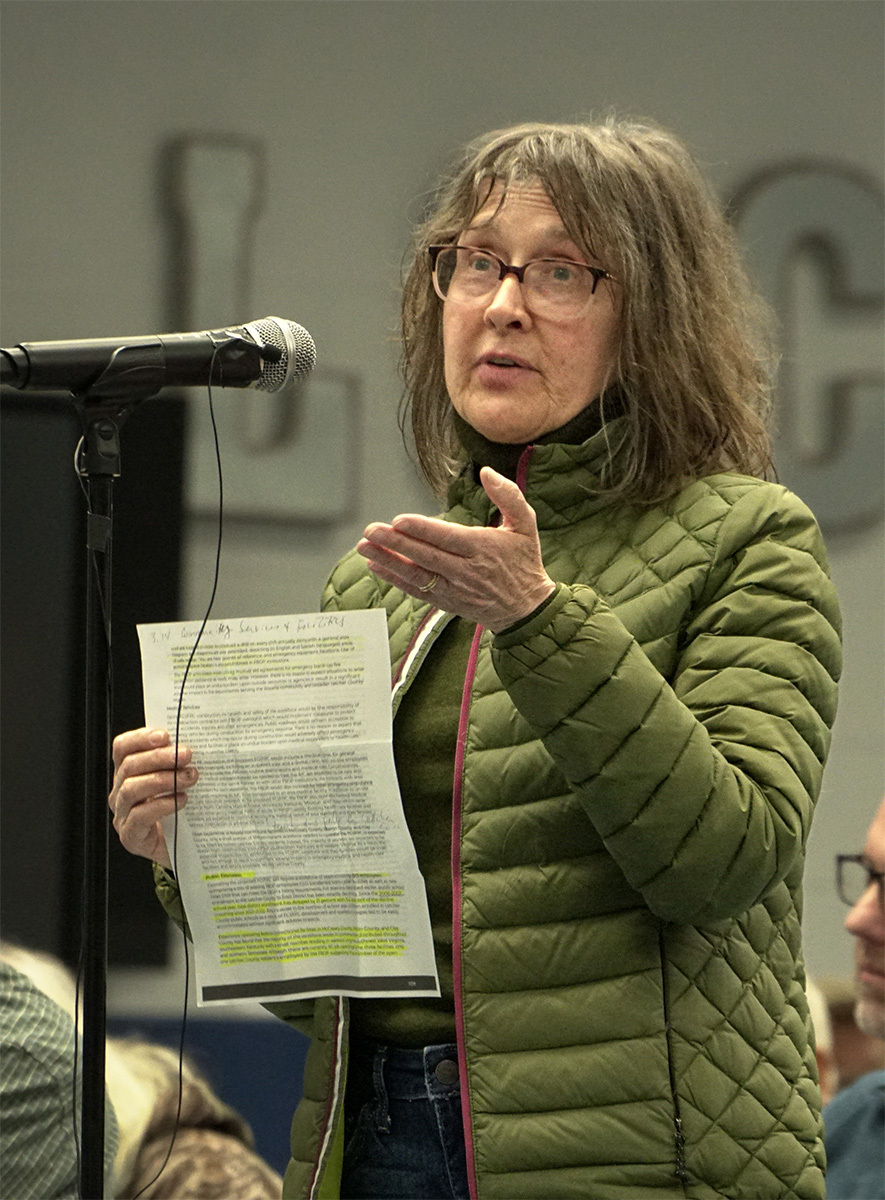

Header image: Skylar Davis