American Purgatory: Prison Imperialism and the Rise of Mass Incarceration

Benjamin Weber

The New Press, $28.99 (hardcover)

Ruchell Magee, one of the nation’s longest-held prison radicals, was finally freed in August of this year, after a total of sixty-seven years in captivity, most subsequent to assisting Jonathan Jackson’s attempt to free political prisoners in the Marin County courthouse in 1970. Though himself shot in the chest, Magee was the only member of the group to survive this audacious act. Three of his comrades died that day, as did the presiding judge; three others were injured. Bettina Aptheker has argued that only guards pulled triggers.

Magee, who died in October, is one of the “world-famous” incarcerated people whom historian Benjamin Weber mentions in the epilogue of his first book, the sweeping American Purgatory, which probes the necessity of internationalism in contemporary anti-carceral activism. His survey attempts to restore the legitimacy of this opposition and to explain why it arose. Weber looks to a wide range of locales and periods in his analysis of the relationship between imperialism and incarceration, from the Caribbean to the Pacific, from the Florida coast to the Puget Sound. Resistance, he finds, occurred in all of them.

In this account, Magee is but one example of the geopolitical dimensions of the U.S. prison system. Magee understood himself to be a “slave” in the prisons of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, subject to capricious forms of domination and shorn of political rights afforded to citizens. As a slave, he asserted a right to rebel. This political disposition would be echoed by other incarcerated Black militants, as Orisanmi Burton has noted in his essential new book Tip of the Spear. Some, as Weber notes, even used a vocabulary of war.

How empire, war, slavery, and incarceration are singularly entwined in the history of our nation, and even before that, is what American Purgatory sets out to establish. It does so by exploring, among other points, how the United States experimented with penal colonies beyond its borders, caged liberation movements across the Pacific, and relied on convict labor to build the infrastructure of global capitalism in places such as Panama.

Looking at the prison in this light reveals the inadequacy of nationally centered narratives, of the prevailing assumption that the history of the United States is the history of a nation, not an empire. Even people who are critical of U.S. history, including through the lens of its awful prison system, can fall into this trap. Once alerted to the trap, it grows difficult not to see the parochialism of a purely national, rather than imperial, history as itself part of the U.S. imperial project. The trap is set by the ideology of empire itself. Asserting that empire matters to the history of incarceration, as Weber does, is crucial. It also requires that mobilizations contesting the centrality of the prison to U.S. state power engage in practical forms of internationalist solidarity with those opposing prison power overseas.

Writing from Algiers in 1972, members of the International Section of the Black Panther Party assessed the situation in the United States, where increasing numbers of their comrades were getting locked behind bars. Algeria, independent from France for less than a decade, was, for a brief moment, a beacon and haven for Black radicals fleeing political repression in the United States. The International Section of the Panthers, led by the charismatic and truculent Eldridge Cleaver, used the North African nation as a base. There the group could mount a critique of U.S. imperialism and build solidarity with national liberation movements around the globe. It was from Algiers that Cleaver broke with the Oakland-based party, then under the leadership of Huey P. Newton, because he believed Newton had deviated from the necessity of making a frontal assault on imperialist powers, as national liberation movements in Vietnam or Mozambique were doing.

For the International Section, the prison was central to political repression, particularly in the United States, and many of its members ended up in Africa because they were at risk of or had escaped incarceration. If the prison were a political tool, then it made sense to understand movement comrades behind bars as political prisoners, as a number of radicals were beginning to argue. Criminal charges, in this sense, were not always apolitical.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Yet the International Section went one step further in its analysis. Along with Panthers based in New York, these militants pointed out that political prisoners could easily garner sympathy. Their cause seemed just. Their treatment was unfair, if not morally reprehensible. But housed alongside political prisoners were prisoners of war. They were less sympathetic.

“The difference between prisoners of war and political prisoners,” the International Section wrote in an issue of Right On!, a dissident Black Panther Party publication, “is that prisoners of war participate in the necessity to destroy the oppressive system through counterforce and violence.” The rising number of prisoners of war in jails and prisons, who were “the most feared and hated” by prison authorities, was testament to the “growing armed struggle for liberation in America” that was “continuing to expose the illegal judicial system of imperialism.”

Empires do not recognize prisoners of war; they disavow them. If imperial authorities were to admit that managing an empire entailed making war, it would confer legitimacy and legal rights on those opposing and resisting empire. Although Weber does not adopt Cleaver’s stances on what is to be done to resist repression, he makes clear, as the Black Panthers grasped, that war makes empires, and empires build prisons. And these prisons cage people who oppose war and empire. This “protest tradition” is a key theme and topic of Weber’s analysis, which offers “a more complex framework for understanding the roots of anti-Black carceral violence within and beyond borders” than geographically narrow prison studies typically adopt.

Throughout American Purgatory, Weber makes an effort to identify consistent mobilizations to oppose empire, which historically have resulted in this opposition’s incarceration. Yet this approach prompts a reflection on the distinction between a protest tradition and a political strategy. If we’re not careful in making this distinction, we risk inadvertently flattening historical eras and conflating political tendencies. This, in turn, risks obscuring how particular policymakers in the seemingly distinct fields of imperial management and prison management collaborated at particular moments.

Their collaborations were often a response to resistance movements, but how they responded, in turn, shaped the different tactics that militants adopted. Martin Luther King, Jr., spent time in a Birmingham jail as what we might call a political prisoner. Magee was a prisoner of war. And Cleaver fled to avoid becoming either. They were all emblematic of a broad-based protest tradition, but their philosophies and strategies differed dramatically.

Weber’s story begins before the birth of the United States, in the land today called Florida, where the powerful Creek and Seminole nations once welcomed fugitives from slavery. But his conjunction of war, empire, and prison finds its highest stage at the turn of the twentieth century, when this expansionary but brittle union of states took formal colonies overseas. Weber puts the African American experience at the center of this history, arguing that “the prison system has produced racial hierarchy,” and pointing out that Black incarceration within the United States does “appear little different” from incarceration of insurgents in the U.S. colony of the Philippines.

Emphasizing empire in an account of the rise of the prison dispels the common causal argument that places crime or social disorder first and incarceration as the response. Instead, Weber suggests that the genesis of U.S.-style prisons, and “criminal transportation and penal colonization,” which removed people from a given territory and relocated them, was not connected to any clear crime surge.

Due to this reframing, the core of American Purgatory investigates both the significance of prisons to imperialism and the lasting consequences of the history of “prison imperialism.” Weber points out that, in each location around the globe where the United States expanded its dominion, it built prisons and relied on the coerced labor of the incarcerated. Political repression of those who have resisted imperial expansion has also relied on human caging, both abroad and at home.

The value of analyzing the prison, and its expansion and reform, through the lens of imperialism is that, according to Weber, “penology and foreign policy actually share a set of foundational theories and continue to employ common assumptions about preemption and deterrence, containment and incapacitation, retribution and rehabilitation.”

Yet American Purgatory is not exactly about penology and foreign policy. For Weber, penology is mostly a skein of scientistic and moral justifications for racializing social control, while foreign policy is mostly a set of rationalizations for imperialist ambition and colonial expropriation by force.

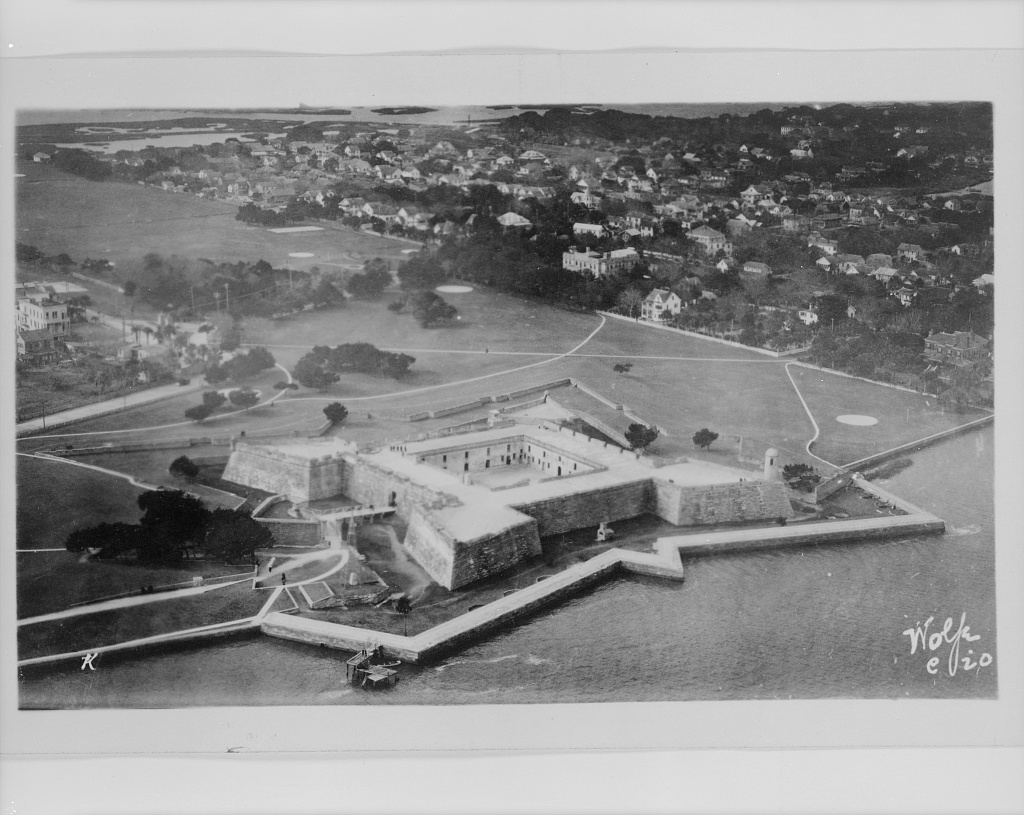

True, ideological affinities are important, but the practical mechanics need to be explained, too, which Weber does by exploring the paradox of the fixity of a prison site—immobile and immobilizing—and the necessity of motion to imperialism’s expansionary drive. Prisons make places, and some of the places they have made have been sites of containment and control now for centuries. Fort Marion, for example, in St. Augustine, Florida, is a place I remember visiting as a child, wowed by its sharp lines and imposing walls. The now-decommissioned fort’s centrality to the wars of conquest that upheld slavery and extirpated Native populations was something I could only dimly grasp. Thanks to Weber, I now better understand how Fort Marion was central to the imperial relabeling that the Black Panthers resisted: Its prisoners of war were supposedly no such thing—they were “wards of the state.”

The managers of the state did not necessarily want wards, however. The responsibility of their care was a challenge, and they posed the threat of rebellion. Thus, Weber analyzes what he calls the “Jefferson-Monroe Penal Doctrine,” a program of sequestration and transportation that would forcibly transfer incarcerated people to distant shores. In the process, they would become laborers for empire and help it to expand.

U.S. jurisprudence contains many notorious phrases, and perhaps none as indelible as the so-called convict clause of the Thirteenth Amendment, which eliminated slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Weber reminds us that there is another phrase tacked onto the end of the amendment that gave the convict clause wide geographic reach: “or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” In other words, slavery was abolished anywhere U.S. law reached, but involuntary servitude attendant to criminal conviction was possible both at home and in faraway places. Weber looks at the Panama Canal Zone, a location dense with capitalist and imperialist interest, as an example of how the United States exported its infamous exception to slavery’s abolition.

Whether in the Philippines or in the mainland United States, opponents of U.S. rule—and especially of its harsh regimes of punitive labor—found themselves branded as rebels, threats to sovereignty and law and order. Prisons became their destination, as soldiers and police rounded up revolutionary leaders and regular people alike. Weber uses the word counterinsurgency to analyze this process of criminalization. It is a term I have explored in my own book, Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing. Although the precise origins of the term counterinsurgency are a bit hazy, it dates to the late 1950s, even if some of its practices, as Weber observes, go back farther. The anachronism of how Weber uses it here raises some questions about the scope and argument of American Purgatory. The term’s development and application attempted to deviate from the practices of formal imperialism, addressing U.S. fears that national liberation movements were vehicles for communist revolution, or susceptible to communist subversion.

The closing chapters of American Purgatory, focused on the 1930s to 1970s, offer accounts of a few episodes that will be familiar to many readers, including the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, the occupation of Alcatraz, and the incarceration of Assata Shakur.

It is absolutely the case that jails and prisons were central devices in the repression of Black radicals in the United States in the twentieth century. But even as imprisoned radicals such as Shakur and Claudia Jones mounted incisive critiques of imperialism, Weber leaves it largely to the reader to connect the dots of how the “prison imperialism” he describes in the U.S. colony of the Philippines is the same as the imprisoning of anti-imperialists in more recent history. Nor does he adequately account for the differences among settler colonialism, formal colonialism, and informal variants of U.S. empire of the Cold War and War on Terror eras—and whether these differences might be germane to the instrumentalization of the prison in each.

After looking abroad for much of American Purgatory, in these final chapters Weber reterritorializes his analysis to remain within the United States—a curious analytic maneuver for this particular moment in U.S. ascendancy. This was, after all, when the country became the global hegemon with the power to consign people to cages nearly anywhere, largely through proxies. Yet colonial empire was different. By default, in the absence of a precise argument about what incarceration does for empire as the geopolitical situation transforms, it appears that little has changed since the 1500s. But, given the book’s focus on resistance, is that a useful analysis? Or even one that would be recognizable to the imprisoned radicals, mostly strict Marxist-Leninists, whom Weber is aiming to honor?

This is not to discount Weber’s admirable commitment to thinking about radical politics in tandem with state policy. In this regard, American Purgatory does two things well. It introduces readers to this protest tradition in which radicals have been incarcerated for opposing imperialism, or else developed anti-carceral critiques because of their recognition of the prison’s centrality to empire. And it advocates placing the history of incarceration into the history of U.S. empire, and vice versa. These are much-needed efforts, encompassing a vast and complex history that could easily fill ten books.

If anti-war radical Randolph Bourne once declared that “war is the health of the state,” this book indicates that prison is the health of empire. Future works will need to dwell in greater detail on the concrete mechanisms connecting empire and incarceration, and how the preservation of that connection has required that the two evolve in tandem. Such an exploration will inform the protest traditions of tomorrow.

Image: Aerial view of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument in Florida. (Library of Congress.)